From the great plague to the 1918 flu, history shows that disease outbreaks make inequality worse

Accounts of previous epidemics – by Samuel Pepys, Daniel Defoe and Katherine Porter – warn of mistakes that we risk repeating.

- 11 June 2021

- 6 min read

In May 2021, virologist Angela Rasmussen reflected how “if the last 18 months have demonstrated anything, it’s that we would do well to remember the lessons of past pandemics as we try to prevent future ones”. This includes ensuring we come out stronger.

Witnesses of past disease outbreaks can help with this. While they don’t offer definitive answers on what to do next, they warn us rising inequality is inevitable after a pandemic and needs to be actively confronted if it’s to be avoided.

Consider the great plague of London in 1665. As it began to abate, naval official and diarist Samuel Pepys noted that his wealth had more than tripled that year, despite the terrible times many were experiencing.

Even so, he regretted the expense of leaving London to avoid the danger. Pepys had had to fund lodgings for his wife and maids at Woolwich and for himself and his clerks at Greenwich. His experience stood in stark contrast to those Londoners who lost their livelihoods – and the 100,000 who died.

We can see the same social and economic inequalities becoming more pronounced today. Amazon’s Jeff Bezos and Tesla’s Elon Musk have increased their net worth by billions of dollars during the pandemic, while many of their employees have faced coronavirus risks in the workplace for little extra pay.

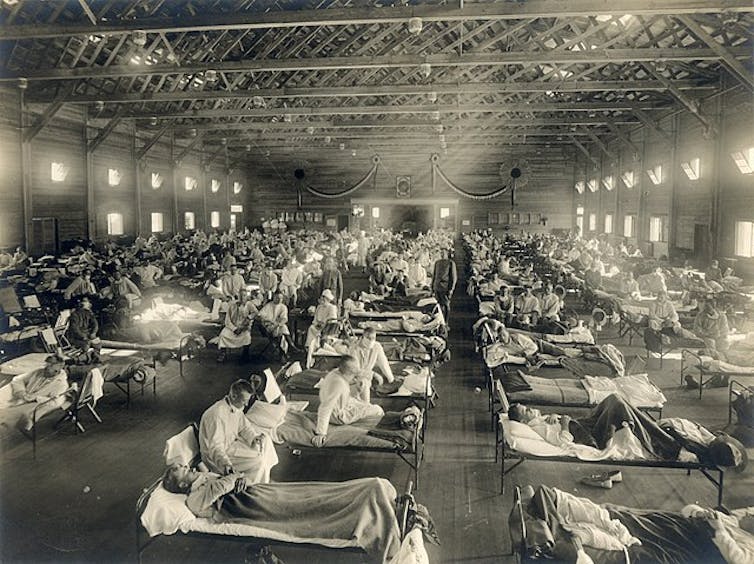

Similarly, during and after the 1918 influenza outbreak – in which it’s estimated a third of the world’s population was infected and around 50 million people died – purveyors of medicines sought to make a profit. In western countries, this was accompanied by panic buying of quinine and other products for treating and avoiding the flu.

Have you read?

Today, there’s controversy as wealthy nations stockpile vaccines and promising potential treatments. Despite Covax being created to spread vaccines equitably, distribution has been strongly in favour of wealthy countries. In modern ways, we’re replicating the problems of the past.

Charity increases too

Yet in such crises, alongside greed and inequality there’s also the chance for acts of charity. In Daniel Defoe’s A Journal of the Plague Year – a fictional account of the great plague, published many years later in 1722 and written in voice of someone who lived through the event – the narrator, H.F., comments:

This misery of the poor I had many occasions to be an eyewitness of, and sometimes also of the charitable assistance that some pious people daily gave to such, sending them relief and supplies both of food, physic, and other help, as they found they wanted.

H.F. notes that while private citizens were sending funds to the mayor to distribute, they were also taking it upon themselves to give “vast sums” to those in need.

And according to real-life accounts of the 1918 flu pandemic, this crisis also saw many acts of charity. Such kindnesses have also been found during this pandemic, with a surge in charitable donations and projects to support those in need. Around the world, giving practices have become more local and expansive, and mutual aid – the practice of helping others in a spirit of solidarity and reciprocity – is increasing.

Yet such practices risk dissolving after the current crisis.

After the 1918 pandemic, the US quickly forgot the disease that had killed about 675,000 of its citizens. The economic boom that became known as the roaring 20s erased memories. Few social and historical memorials exist.

Katherine Porter’s 1939 short novel Pale Horse, Pale Rider is an exception. It describes Miranda’s experience of the 1918 outbreak, as she becomes ill and delirious with influenza, but recovers. Yet she finds that the pale rider, or death, has taken her soldier love Adam, who probably became ill from caring for her. It’s a reminder that the trauma of pandemics is deeply personal and shouldn’t be forgotten.

Inequalities persist

As economies today start to recover and growth is expected, we need to remember both the individual suffering and social upheaval the pandemic has caused – and use this to make better decisions about moving forward. History suggests that inequalities so recently exposed and exacerbated will simply reappear again unless we make an effort to fight them.

Consider, for example, a long-unresolved inequality in pandemics: that women and children are especially hard hit. Defoe’s narrator H.F., when considering that poor women had to give birth alone during the plague, with no midwife or even neighbours to help, called it one of the most “deplorable cases in all the present calamity”.

H.F. also argued that more women and children died of the plague than records suggest, because other causes of death were recorded even when the plague was involved. The 1918 flu pandemic also hit under-fives and those aged 20-40 hardest, leaving many infants motherless or orphaned.

In the current pandemic, mothers have too often had to give birth with far less support than desired. They have also borne a greater burden in terms of having to balance employment, childcare and home schooling. The number of children in poverty has also risen, with an estimated 14% of British children having faced persistent hunger at some point during the pandemic.

Planning for the future

Yet looking at the literature from the past does not mean being doomed to repeat patterns of inequality. Hopefully, it can inspire the opposite. The £20 weekly universal credit uplift introduced in the UK at the start of the pandemic is currently only extended until September. As we emerge from the crisis, perhaps it’s time to consider radical changes to the status quo, like universal basic income and heavily subsidised childcare.

Now is the time for policymakers and society to think big and be bold. Should we be so lucky as to have a swift and strong economic recovery as after 1918, let’s not forget that another disaster, whether a pandemic or something else, will bring the weaknesses exposed throughout history back to the fore.

Maybe we should not look forward to the day when normal is back, but remember the hope from early in the pandemic – that it might catalyse a new and better normal.

Authors

Janet Greenlees, Associate Professor of Health History, Glasgow Caledonian University

Andrea Ford, Researcher in Medical Anthropology, University of Edinburgh

Sara Read, Lecturer in English, Loughborough University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Disclosure statement

Janet Greenlees has received funding from the Wellcome Trust, Economic and Social Research Council, British Academy and various charities within the US and Great Britain. This piece does not directly relate to any funded projects.

Sara Read has received funding from the Arts and Humanities Research Council. This piece does not relate to any funded project.

Andrea Ford does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Partners

Glasgow Caledonian University provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation UK.

Loughborough University provides funding as a member of The Conversation UK.