A history of quarantine

Since COVID-19 was declared a global pandemic, many countries around the world imposed some form of quarantine to control its spread. What can the history of quarantine teach us about isolation and lockdowns now?

- 11 March 2021

- 4 min read

- by Tetsekela Anyiam-Osigwe , Jacques Schmitz

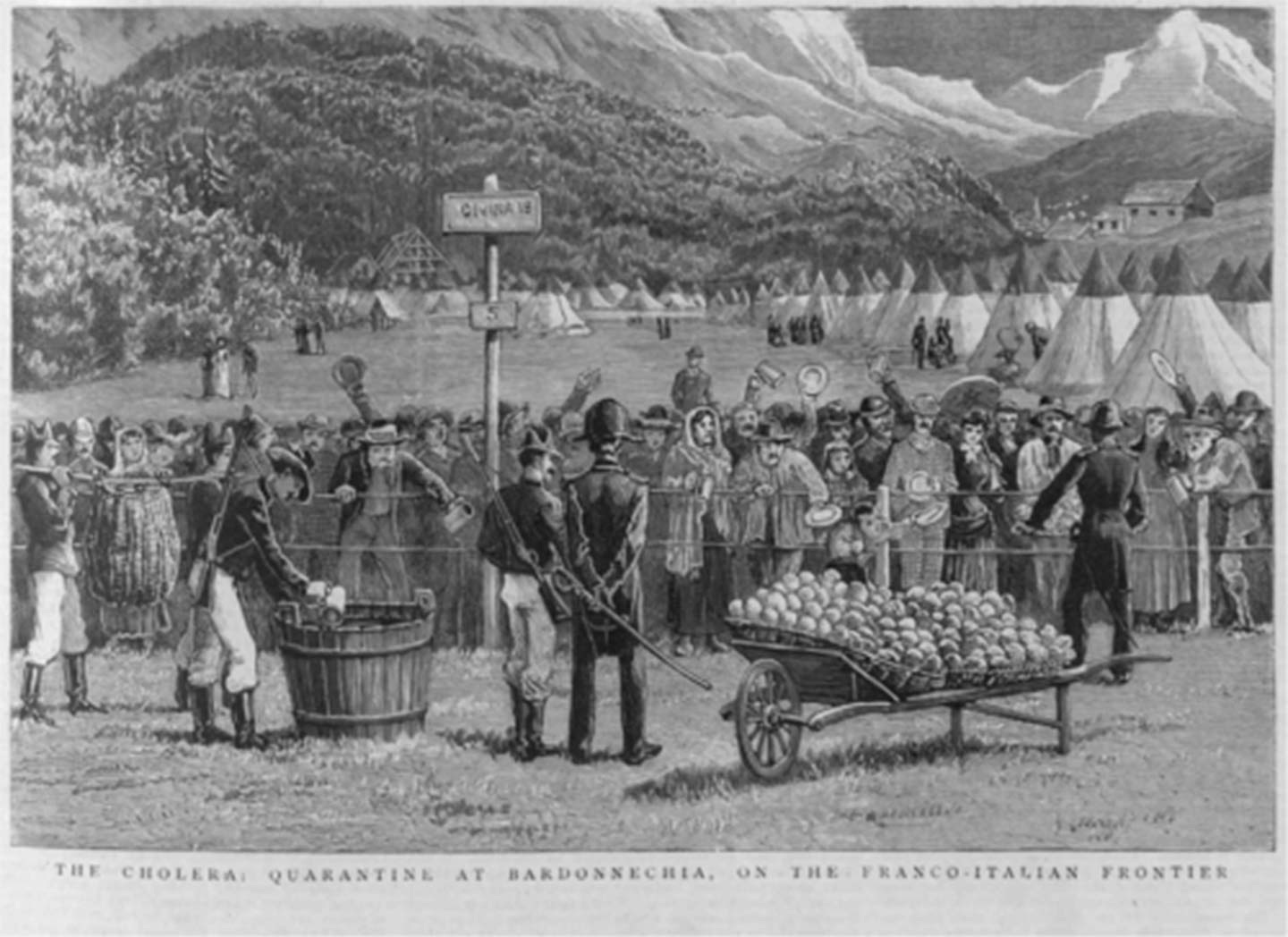

Italy in the time of cholera was certainly an unusual time. As the disease spread through the country in the 19th Century, anyone arriving the country was kept for observation, quarantining for seven days in hastily constructed lazarettos, or pesthouses. In places like Bardonecchia over 8,000 people quarantined and in Pian di Latte around 16,000. They were not alone. Surrounding these quarantine stations were troops, standing guard to prevent people from escaping. The only ticket out of the lazarettos was a clean bill of health.

At the time, this represented one of the most effective organised institutional responses to disease control, helping to limit the spread of cholera. These measures were, however, not new. The Italian quarantine was inspired by quarantine regulations that helped Europe contain the plague centuries before. The idea of quarantine as a coordinated public health response to disease outbreaks was straightforward: people who may have come into contact with transmissible diseases needed to be separated from the rest of the community in order not to risk spreading the disease.

The long history of quarantines

Quarantine has a long history that dates back to biblical times. The Old Testament’s Book of Leviticus details how people with leprosy were effectively isolated from the rest of the community. When the bubonic plague emerged in the 1370s, European cities also started their own quarantine system. In Venice, a major port at the time, maritime travellers that could potentially have the plague were required to wait on ships for forty days before they and the goods they carried could come ashore. Even with the Great Plague of London in the 17th century, quarantine stations were provided by parishes to allow infected people to isolate. As in Bardonecchia, watchmen stood guard outside to ensure that no one either escaped or tried to get in.

Have you read?

Beyond the plague, quarantine – as well as various forms of self-isolation and physical and social distancing – has been adapted to respond to and contain other outbreaks, including smallpox, yellow fever, the flu epidemic, severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and the Ebola virus.

COVID-19 era quarantines: lockdowns, self-isolation and hotel seclusion

Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, nearly every country in the world has imposed some form of quarantine, such as stay-at-home orders or mandatory seclusion for foreign visitors. As early as January, China was building a quarantine centre on the outskirts of Wuhan, as well as imposing its own local lockdown together with other cities in Hubei province. This put more than 20 million people under quarantine. Many countries implemented similar measures, with curfews and local, regional and even national lockdowns forcing school and business closures, limited travel and nearly non-existent in-person interactions with people from different households.

This was certainly a shock to people’s version of normalcy, but a necessary one in the context of a pandemic that was spreading rapidly and without a viable vaccine. Even as vaccines currently begin to roll out around the world, quarantine still affects many people,particularly travelers. In countries from Australia to Rwanda, arriving passengers face a mandatory hotel quarantine, whilst in other countries, like Nigeria, travelers are required to self-quarantine at home for seven days after which they must take a COVID-19 test.

It is not always easy to face such measures of isolation, and even if quarantine has proved effective in controlling outbreaks throughout the course of history, it has not always been welcomed by a public sceptical of both extensive government intervention and the restrictions on personal freedom that accompany mandatory self-isolation. Nevertheless, despite the significant sacrifices that everyone must make for it to work, it ultimately keeps us safe, just as it did for previous generations.