Hope and despair on Nigeria’s malaria frontline

A scourge that has defied centuries of efforts to control it, malaria continues to run riot in many Nigerian communities, inflicting unimaginable suffering on families across the nation.

- 27 November 2024

- 7 min read

- by Eric Dumo

Aina Ogundare tightly clutched her crying three-year-old baby, Tunmise, as she waited to see a doctor at the Ikorodu General Hospital last Wednesday morning.

Looking visibly worried and ruffled, the 34-year-old was surrounded by dozens of other women who had defied an early morning downpour to besiege this Lagos hospital in search of medical care for their loved ones. Laboratory test results confirmed that the little girl had malaria.

“I cannot afford to lose her. I will do anything I can to ensure she overcomes this sickness,” the young mother said as a nurse tried to calm her fears.

Ogundare has valid reasons for expressing such worry. Four years ago, she lost her only child at the time, Ayomide, to malaria.

Though the arrival of Tunmise helped reduce the impact of that loss, the constant threat posed by malaria has ensured that the shadow of that tragedy continues to lurk.

“I cannot count the number of times that my baby has fallen ill to malaria,” Ogundare told VaccinesWork as she walked out of one of the three consultation rooms on the ground floor of the hospital.

“The situation has drained our resources and taken a huge mental toll on us,” she added, before heading to the dispensary to purchase prescribed drugs for her daughter.

Single mother of twin boys Kelechi Ukatu is also familiar with the pain and nightmare that malaria brings. Since she gave birth to her children, the parasitic disease has ensured that she knows only little sleep. Day and night, at different times, malaria has infected her boys, leaving her to contend with a heavy burden.

Apart from the resources that go into seeking treatment each time they fall sick from malaria, the psychological trauma that comes along can be devastating.

“There have been occasions when we are forced to wake up in the middle of the night to rush the children to the hospital because of malaria. We have become frequent visitors to different hospitals because of this situation,” Ukatu says.

The impact of conflict

In other parts of Nigeria, especially in the northeastern region, where conflict has sacked communities and forced families to take refuge in camps, the threat and danger posed by malaria remain real and severe.

In Borno, one of the six states in the region and epicentre of the insurgency that has left behind a full-blown humanitarian crisis, malaria spares no one. Young and old have been left to contend with a ruthless killer.

“My neighbour lost a child to malaria in September after floods overran our community,” Aisha Aliyu, a mother of one living in Maiduguri, Borno’s capital, recalls.

“Less than a week after that incident, my son, Ali, also fell ill from the same disease. I was confused and afraid that I was going to lose him.

“Though he is well now, he has not been the same child again, especially since we don’t have a treated net to protect him from mosquitoes,” she added during an interview with VaccinesWork.

Fatima Hassan, who also resides in the same city with her daughters, lost a nephew to malaria two years ago. Following a rise in malaria cases in her neighbourhood since September, after floodwater from a collapsed dam overran parts of the region, she has grown worried for the safety of her girls.

“I cannot count the number of times that my baby has fallen ill to malaria.”

- Aina Ogundare, mother

“The threat of malaria in this part of the country has increased over the last two months. The situation has exposed our children to the disease, and this is affecting our lives a lot.

“We hope that the authorities do something about this problem soon, before we lose more lives to malaria,” she said.

Nigeria’s malaria burden

Saliu Ibrahim, a medical doctor in Kebbi, the state with the highest malaria prevalence in the country, said that nearly eight in every ten cases attended to at the government facility where he works is malaria-related. He fears for the worst if urgent measures are not taken to tackle the situation.

“As medical personnel, we are mostly overwhelmed as a result of the number of malaria cases we attend to every day. The number of casualties related to the diseases makes it a serious crisis that must be quickly looked into by higher authorities,” he said.

The leading cause of death among children five years and below as well as pregnant women in Nigeria, malaria continues to wreak havoc across the country, inflicting households and entire communities with wounds that may never fully heal.

“Malaria hampers productivity and slows down the national economy as a result of illness and death to individuals. Therefore, the amount lost to this disease every year is surely more than what is being projected.”

- Peter Agadibe, a consultant pharmacist based in Lagos

WHO’s 2023 World Malaria Report reports that Nigeria accounted for 27% of the global malaria burden – the highest in the world – with a national prevalence rate of 22% in children five years and below. In the northeast region, the figure is as high as 49%.

Transmitted to humans by female Anopheles mosquitoes, malaria is a common fixture all year round in the country, especially during the rainy season when the flooding of communities encourages disease spread. Health authorities put the economic burden of the disease on Nigeria at US$ 1.6 billion annually, pointing out that the amount could rise to US$ 2.8 billion by 2030. But experts believe that the cost is, in fact, higher when considering the direct impact on individuals and households.

“Malaria hampers productivity and slows down the national economy as a result of illness and death to individuals. Therefore, the amount lost to this disease every year is surely more than what is being projected,” Peter Agadibe, a consultant pharmacist based in Lagos, said.

Professor of Paediatrics, and Strategic Adviser to Nigeria’s Minister of Health on Malaria Elimination, Olugbenga Mokuolu identified inadequate funding, health system weakness, including depletion of the workforce, insecurity, environmental challenges and behavioural patterns as some of the factors responsible for the country’s malaria crisis.

“My second child suffered from frequent malaria, and unfortunately I didn’t know about it on time until she died. My baby is five months old now, and I would like to give him the vaccine to protect him.”

- Permanent Epiere, a mother of two in Onuebum community

“We have issues with insecticide resistance, behavioural problems around inadequate use of available nets, poor diagnosis and [poor] treatment practices. While we have made progress on the fight against malaria, the challenge is that at any point in time, the resources deployed are a fraction of what is needed.

“The problem requires a multisectoral response, mobilising resources, and innovative approaches to improve access to preventive and treatment tools,” he said.

Have you read?

Vaccines arrive

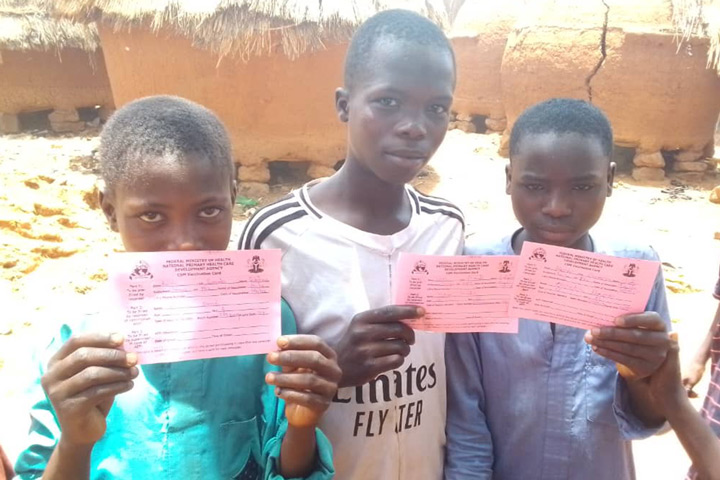

In October 2024, the Nigerian government took their first delivery of malaria vaccines. Designed to bolster already implemented interventions like the distribution of insecticide-treated nets to households, the vaccine will soon be rolled out in Kebbi and Bayelsa states. Over 800,000 doses are expected to be distributed during this initial phase.

Nigeria’s Minister of Health and Social Welfare, Prof Ali Pate, while receiving the vaccines in Abuja last month, said that the arrival of the malaria vaccine was a huge step in the country’s effort to reduce malaria cases and related deaths.

“With the support of UNICEF, Gavi and WHO, we are on a path toward achieving our goal of a malaria-free Nigeria,” he said during the occasion.

While the arrival of the preventive vaccine has offered some relief and hope to parents in parts of the country, in Bayelsa, one of the two states where the first roll-out will take place this month, some mothers wished the vaccine had come earlier.

“My second child suffered from frequent malaria, and unfortunately I didn’t know about it on time until she died. My baby is five months old now, and I would like to give him the vaccine to protect him. The vaccine will be very helpful for us because many children die due to malaria,” Permanent Epiere, a mother of two in Onuebum community under Ogbia council area of the state, told VaccinesWork.

Prof Mokuolu sees a ray of hope with the arrival of the new vaccine. He believes that the roll-out later this month will lead to reduced hospital visits for children and increase survival rates for those within the most endangered age bracket.

“The malaria vaccine offers an immense opportunity as an added tool to the fight against malaria,” he said.