How Africa defeated meningitis A

The MenAfriVac vaccine has eliminated the leading cause of bacterial meningitis in Africa. A new vaccine covering other major strains could be a further game-changer.

- 5 October 2023

- 11 min read

- by Linda Geddes

Jean-Francois was a star pupil, a talented footballer; a boy who had everything to live for. He was admitted to hospital in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso in 2006, after waking up one morning with a splitting headache, which rapidly deteriorated into a life-threatening illness.

Though the 18-year-old survived the episode, he was left completely deaf. Months later, he was playing football in a yard near his house when the ball rolled into the street, and he chased after it.

"When you live through one of these meningitis epidemics in Africa, it sears your soul."

– Dr Marc LaForce, infectious disease doctor and epidemiologist

"He never heard the truck that ran him over," says Dr Marc LaForce, an infectious disease doctor and epidemiologist who met Jean-Francois during his hospital stay. "Here was a potential president of Burkina Faso who never had a chance, because we didn't have something that we should have had – a vaccine to protect him."

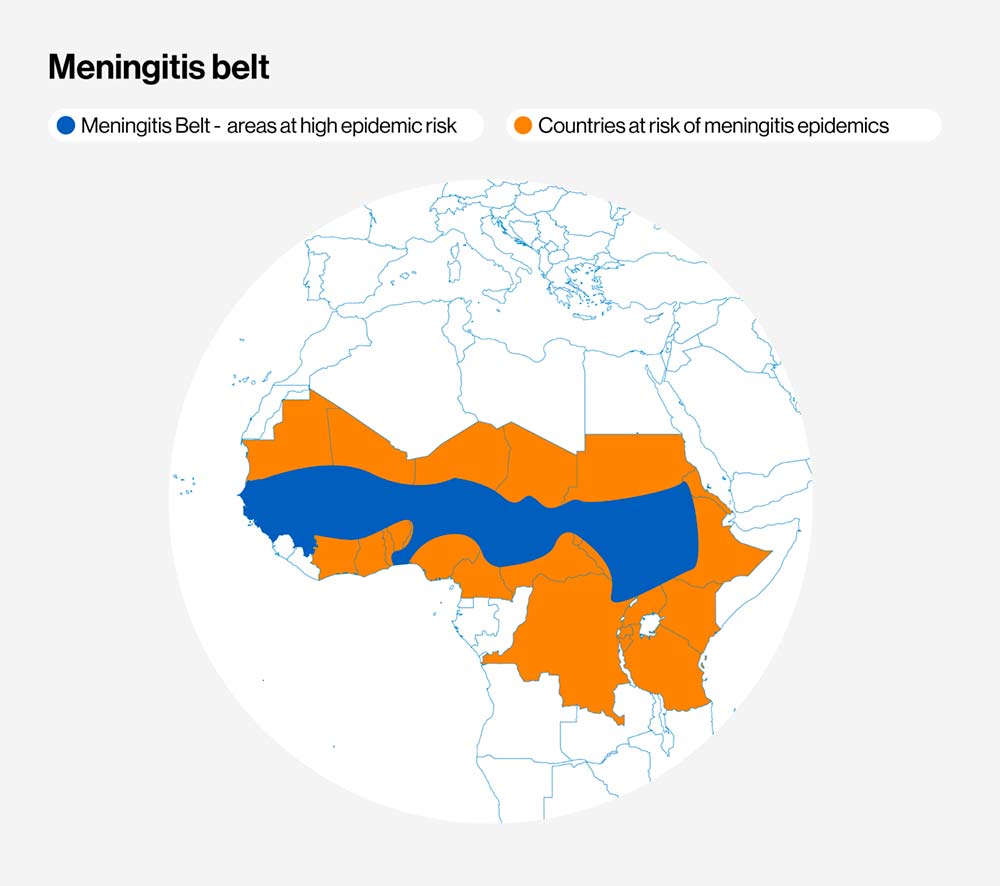

Meningitis is a disease with the power to strike fear into the heart of any parent – particularly those living in the region of sub-Saharan Africa known as the Meningitis Belt, which has the highest rates of meningococcal disease in the world. Historically, major epidemics have swept through these countries every five to 12 years. The disease is fatal in 80% of cases if untreated, with children and young adults going from healthy to critically ill or dying within 24 to 48 hours.

Even when it is diagnosed early, and appropriate antibiotics given, around one in ten patients die, and up to 20% of survivors are left with brain damage, amputated limbs, or, like Jean-Francois, hearing loss.

"When you live through one of these meningitis epidemics in Africa, it sears your soul," says LaForce. "It is impossible to predict where and when they are going to occur, and when they do, the disease strikes unpredictably: you could have four or five cases in one home, no cases in the rest of the village, and then another family with multiple cases just outside the village.

"People are very afraid, so they retreat into their homes. There's no commerce; nothing much happens until the epidemic disappears."

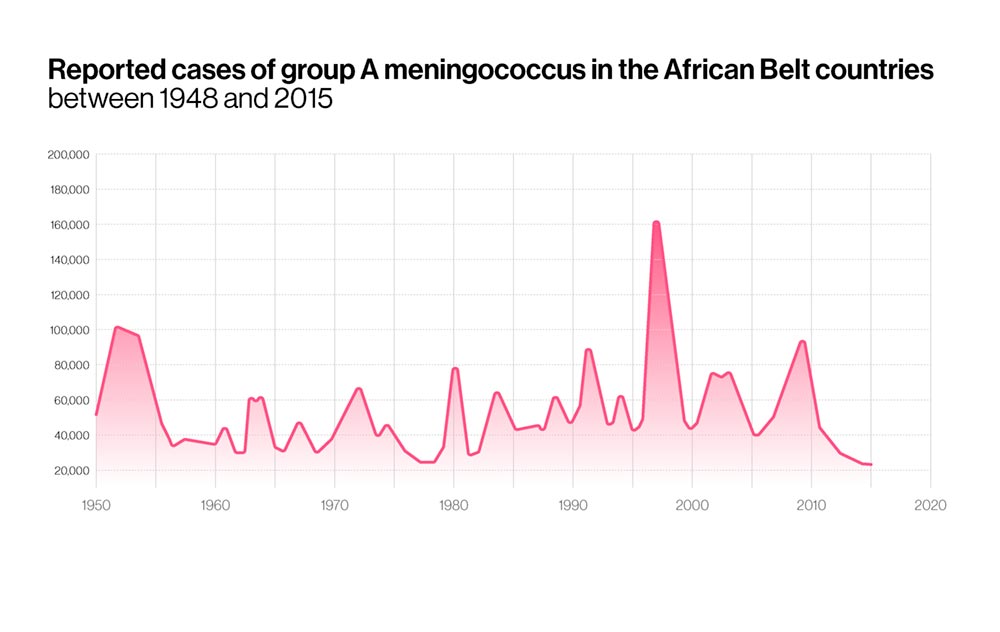

Until little more than a decade ago, epidemics of meningococcal meningitis were a regular feature of Meningitis Belt countries, with up to one in every 100 people becoming infected during the worst epidemics, and the intervals between these outbreaks appeared to be growing shorter. However, starting in 2010, the introduction of a vaccine against Group A meningococcal bacteria, the leading cause of epidemic meningitis, has effectively been eliminated, saving millions of lives. Now the world is on the cusp of another milestone: the roll-out of a vaccine that will protect against four further meningococcal strains.

"What Africa is looking at right now is the possibility of doing something incredibly exciting," says LaForce. "The first step was to eliminate MenA, which was the worst problem. We now have the opportunity of applying the same epidemiologic principles but taking care of all the problem. We're looking at the continental elimination of all meningitis in Africa."

Deadly infection

Meningitis is an infection of the meninges, the thin lining that surrounds the brain and spinal cord. Although viruses, fungi or parasites can also cause it, the bacterial form is the most common and the deadliest. Many different types of bacteria can cause meningitis, but people living in the Meningitis Belt – which stretches across 26 countries from Senegal to Ethiopia – are at particularly high risk of meningococcal disease, caused by Neisseria meningitidis bacteria.

These pathogens can live in the nose or throat without causing symptoms, but occasionally break into the bloodstream and travel to the meninges. This becomes more likely during dry, dusty conditions, which irritate respiratory tract linings. In some cases, these bacteria can also trigger sepsis or blood poisoning, which is what causes the characteristic pinprick rash – although not every patient develops this tell-tale sign.

In Meningitis Belt countries, epidemics typically start at the beginning of the calendar year, when dry, dusty winds from the Sahara start blowing southwards, and cold nights and upper respiratory tract infections inflict further damage on people's respiratory tracts. Since 1905 major epidemics have been recorded in this region every few years, but the 1996-97 meningitis was one of the worst in its history, sickening more than 250,000 people and causing at least 25,000 deaths.

"There were many, many cases, and you could see children and young adults dying one after the other," says Dr Marie-Pierre Preziosi, who was working as an epidemiologist in southwest Senegal in 1996, and now leads the WHO's Defeating Meningitis by 2030 initiative. "It is terrifying because it happens very fast – within 24 hours you can develop a high fever and then die. And it is not only not young babies that are affected, but children, adolescents and young adults."

Although polysaccharide meningitis vaccines were available, they tended to be deployed as part of a "reactive vaccination" strategy, which involved immunising the epidemic district and surrounding areas. These vaccines were also expensive, provided only short-term protection, and were largely ineffective in infants and young children.

"The protection from polysaccharide vaccines is gone within a couple of years, but it was felt that if you could introduce the vaccine at that time, it could provide some local immunity and bring these epidemics under control," says LaForce.

However, affordability and getting these vaccines to where they were needed quickly enough, was an ongoing challenge. "More often than not these reactive campaigns occurred months after the epidemic had gone by. When one sat down and did an analysis across countries, across years, and across the amounts of vaccine that had been purchased, it was impossible to determine that any effect had occurred through these reactive strategies," LaForce says.

A vaccine for Africa

Alarmed by the devastating impact such outbreaks were having on children and young adults approaching the peak of their economic lives, in 1997, health ministers from across the meningitis belt approached the WHO to develop a new strategy to prevent these epidemics from occurring.

This meant developing a low-cost vaccine that could be given to all high-risk groups, including infants and young children, and which would confer lifelong protection against Group A meningococcal bacteria.

In 2001, the Meningitis Vaccine Project was born, and LaForce appointed its director. Led by WHO and the Seattle-based health organisation, PATH, and funded by the Gates Foundation – but with African researchers and health ministries involved at every step – its aim was to develop, test and license an affordable Group A meningococcal conjugate vaccine in sub-Saharan Africa.

“The first step was to eliminate Men A, which was the worst problem. We now have the opportunity of applying the same epidemiologic principles but taking care of all the problem. We're looking at the continental elimination of all meningitis in Africa.”

– Dr Marc LaForce, infectious disease doctor and epidemiologist

The project began with an intensive research phase to better understand the disease and the infrastructure that would be needed to introduce such a vaccine. LaForce and his team also began reaching out to big pharmaceutical companies about developing this vaccine, but no multinational vaccine manufacturer was willing to make a vaccine that was cheap enough for African governments to afford.

Unperturbed, they decided to create their own vaccine company in partnership with The Serum Institute of India, which agreed to produce the vaccine for less than US$0.50 per dose. Between 2003 and 2010 the partnership worked tirelessly to develop, test and license this vaccine.

Though there were many obstacles in their path, the team persevered – with Jean-Francois' untimely death only adding to their momentum. "From the entire team's standpoint, his story became a beacon, frankly. Whenever we got discouraged, the answer was to keep going," LaForce says.

Have you read?

By 2005, a prototype of the Meningitis Africa Vaccine (MenAfriVac) was ready for testing in 74 healthy adults in India. This successful safety test was followed by larger Phase 2 trials in Mali and The Gambia, which demonstrated that the vaccine was not only safe, but triggered high levels of antibodies in those who received it.

Preziosi, who was leading the vaccine's clinical development, was one of the first people to see the data from these trials. She vividly recalls the moment when they crossed her desk: "I called my bosses and I said we are on the voie royale – the golden ticket . I knew when I saw this result that the product was working, and we were going to make this happen," she says.

Lining up for immunity

On December 6, 2010, the vaccine was introduced in Burkina Faso, with 95% of Burkinabes between the ages of one to 29 years – 10.8 million people – vaccinated within ten days. Its impact was as dramatic as it was sudden: "Between December 2010 and June 2011 we went from a lot of meningitis cases to practically zero," LaForce says. "We had only one documented case of Group A meningococcal meningitis – which was in an unvaccinated individual who lived in a desert area between Mali and Burkina Faso."

Hearing what had happened in Burkina Faso, other African countries started demanding access to the vaccine.

Over the next ten years some 360 million people across sub-Saharan Africa were immunised, and the impact has been huge: before the vaccine was introduced, Group A meningococcal disease accounted for 80–85% of meningitis epidemics in the Meningitis Belt. As of April 2021, 24 of these countries had conducted mass vaccine campaigns, and incidence of serogroup A meningitis had declined by more than 99%.

The impact of the vaccine has been felt on multiple levels, says Preziosi, who took over as director of the Meningitis Vaccine Project in 2012. "The first is that it has eliminated Group A meningococcal disease; there have been no reported cases since 2017, and the vaccine has likely prevented close to a million cases since 2010," she says.

"The vaccine has also brought communities in these countries a lot of hope because they've realised that a vaccine could be developed by African researchers – they were the people leading the trials and designing the introduction strategies. For the first time, Africans were not receiving a product that had been tested in high-income countries, and then sold to them after years of use. This was their vaccine."

Preziosi believes that the success of the campaign has also boosted confidence in vaccines more broadly: "Vaccine programme managers in several of these countries told me that it had brought them hope because they'd seen that this new product could eliminate a major scourge, which revitalised their programmes," she says. "People could see this terrible disease going away."

"It has eliminated Group A meningococcal disease; there have been no reported cases since 2017, and the vaccine has likely prevented close to a million cases since 2010.”

– Dr Marie-Pierre Preziosi, director of the Meningitis Vaccine Project

However, challenges remain. Even though meningitis cases have dramatically reduced, other types of non-A meningococcal bacteria also cause epidemics, including Groups C, W, X, and Y. In 2017, outbreaks caused by groups C and W caused more than 14,000 cases in Niger and Nigeria alone.

Meningitis is also caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae (pneumococcus), Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib), and Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B streptococcus) – and although effective vaccines against pneumococcus and Hib are included in most routine immunisation programmes, continued high coverage is needed to prevent infections.

Game-changing vaccine

The good news is that further vaccines are coming. Two vaccines against Group B streptococcus are currently in clinical trials, while an affordable meningococcal conjugate vaccine against Groups A, C, W, X, and Y – developed at The Serum Institute, under LaForce's leadership – achieved WHO prequalification in July 2023. This means the vaccine meets strict international quality, safety and efficacy standards, and can be procured by United Nations agencies and Gavi, The Vaccine Alliance.

"This vaccine has the potential to be a game-changer because it will eliminate epidemics and cases of meningitis not only in the belt, but in the rest of Africa," says Preziosi. "It will be a challenge to introduce, because there are a lot of competing priorities, but there is a high demand for this vaccine, and we think it could also drive the coverage and acceptation of [other] vaccinations. So, we have a lot of hope that it could really make a difference in these countries."

In late September 2023, WHO's Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunization (SAGE) recommended that all countries in the African meningitis belt introduce the new vaccine into their routine immunisation programmes in a single-dose schedule at 9 to 18 months of age. In high-risk countries and those with high-risk districts a catch-up campaign should also be conducted at the time of the vaccine's introduction, targeting all individuals aged 1 to 19 years.

The vaccine is also currently undergoing an additional Phase 3 study in healthy infants in Mali to test its safety and immunogenicity when given alongside measles/rubella and yellow fever vaccines.

“For the first time ever, there is a component not only of preventing the disease but recognising that many people and communities have been affected by lifelong sequelae - including loss of limbs, hearing loss, visual and neurological impairments, and developmental issues - who do not have access to any support whatsoever.”

– Dr Marie-Pierre Preziosi, director of the Meningitis Vaccine Project

Yet vaccines are only part of the solution. In September 2021, WHO launched a global roadmap that sets out a strategy to defeat meningitis by 2030. Its goals are to eliminate bacterial meningitis epidemics, reduce cases of vaccine-preventable bacterial meningitis by 50% and deaths by 70%, and improve of quality of life for meningitis survivors.

Survivor support

"For the first time ever, there is a component not only of preventing the disease but recognising that many people and communities have been affected by lifelong sequelae – including loss of limbs, hearing loss, visual and neurological impairments, and developmental issues – who do not have access to any support whatsoever," says Preziosi, who is leading the initiative.

"First and foremost, we are developing guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of these lasting sequalae, to detect them as early as possible and help people before the effects become too dramatic. We are also working on quantifying how many people are affected, to enable sufficient support for them, and linking with existing NGOs or national initiatives that could help people living with disabilities by providing e.g. cochlear implants and other hearing devices, or wheelchairs."

Such interventions could have saved Jean-Francois' life, and those of countless others like him. But they could also enable meningitis survivors to live happier and more productive lives – ones where we can all imagine a future free from meningitis.