How Indonesia got vaccinated

With 95% of the population now jabbed against COVID-19, Indonesia’s vaccine campaign has trounced pessimistic early forecasts.

- 2 June 2022

- 5 min read

- by Dyna Rochmyaningsih

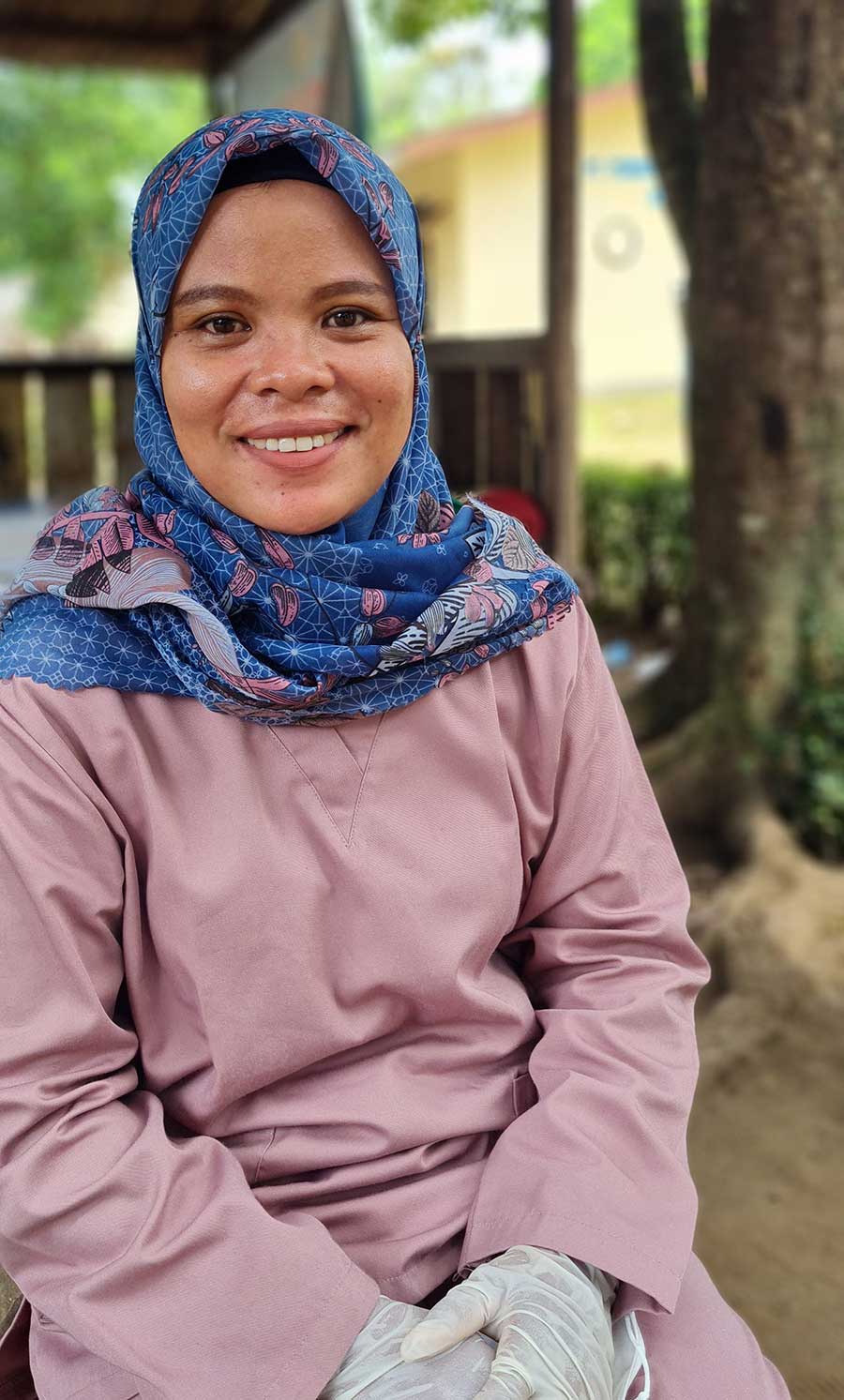

It’s a bright morning, and under the rusty roof of a wooden shack, Nur Fatima is arranging her vaccine kits in their blue cooler box. Mothers with babies in their arms are lingering around her, chit-chatting. Posyandu, a monthly programme for childhood vaccinations in Indonesia, has returned to Sungei Putih, a small village located in Deliserdang, North Sumatra, where Fatima works as a midwife.

The digitalisation campaign, in particular the use of a smartphone application and the electronic vaccination data, has helped Indonesia massively speed up its COVID-19 vaccination rate.

Credit: Dyna Rochmyaningsih

It’s a welcome sign of a return to normalcy. Until the village achieved a high COVID-19 vaccination rate, health workers like Fatima were unable to get on with their regular, life-saving work.“Thanks God, we have already achieved a nearly 100% vaccination rate in our village, so we can focus on our routine immunisation programme and monitoring the health of our children,” Fatima says.

In mid-2021, Sungei Putih, like the other villages across Indonesia, was badly hit by the COVID-19 Delta variant. But, in less than a year, the village has vaccinated nearly all of its people, and has all but extinguished its COVID-19 outbreak.

Sungei Putih is not alone in its success. The village is a testament to Indonesia’s wider achievements in curbing the pandemic virus.

Early in 2021, many observers were pessimistic about Indonesia’s ability to achieve its vaccination target. Given the country’s faltering public health management in the early days of the pandemic, some public health experts doubted that the country’s health systems would be able to vaccinate the more than 250 million people living spread across 6,000 islands on the tight timeline the Ministry of Health set for itself. Some onlookers even suggested that it could take as long as 10 years to vaccinate the whole archipelago.

Credit: Dyna Rochmyaningsih

But, a year later, those assumptions were proven wrong. As of 25 May 2022, 208 million people, more than 96% of the target group, have been vaccinated with first dose. Eighty percent of those already have their second dose. Those figures include the populations of both big cities and smaller rural communities like Fatima’s village.

“I admit that it is an achievement,” says Ilham Ahsanul Ridlo, a public health expert from Airlangga University in Surabaya, East Java.

Have you read?

The success, says Ridlo, stems from the concerted effort made by various major Indonesian institutions. From a transformative digitalisation effort spearheaded by the Ministry of Health, efficient vaccines stock management and distribution led by Biofarma (Indonesia’s vaccine supplier and distributor), to the strict regulations imposed by the Police and National Army (TNI/POLRI), “Every stakeholder has done a good job,” Ridlo says.

The digitalisation campaign, in particular the use of a smartphone application and electronic vaccination data, has helped Indonesia massively speed up its COVID-19 vaccination rate. From his early days in office, Budi Gunadi Sadikin, Indonesia’s Minister of Health, has pushed for digital transformation, which helped facilitate a rapid response when the pandemic hit. The information system that manages all data related to the COVID-19 vaccination programme was quickly developed.

At the national level, Biofarma has used real-time digital systems to monitor vaccines stocks and distribution, enabling them to quickly supply vaccines to the areas where they were most needed. At village level, PCare, an app developed by the Ministry of Health, has helped frontline health workers like Fatima to submit vaccination data to Jakarta in a matter of seconds.

“It also helped me determine who has not received their vaccine dose,” says Fatima. PCare is linked up to PeduliLindungi, a must-have app for every Indonesian citizen which was developed to track the spread of COVID-19.

But Ridlo is quick to point out that Indonesia’s battle against COVID-19 has not only been waged on screens and online. “This digital transformation would have been useless without strict regulations imposed by TNI/POLRI.”

In mid 2021, Luhut Pandjaitan, a military general who is also the Coordinating Minister of Maritime Affairs and Investment, imposed public activity restrictions to respond to the surge of Delta variant infections. Unvaccinated people were not allowed to enter public spaces or to travel between provinces. Those checks acted as an effective nudge – people flocked to the health care centres (Puskesmas) to line up for their jabs.

And amid initially high rates of misinformation and COVID vaccine hesitancy, the support of TNI/POLRI has been instrumental for health workers in rural area. In the early days of the COVID-19 vaccination programme, many people in rural Indonesia doubted the vaccines’ safety and adopted self-protective stances towards healthcare outreach workers.

Dr Henny Andriani, a health care centre head in Galang, North Sumatra, says that she and her team struggled in the beginning.

“[Residents] were consumed by hoaxes and fake news. To tackle the challenge, my team actively visited the villages and public spaces to increase awareness on the importance of vaccines. But it wasn’t very successful until the police joined us,” she says.

Ridlo believes that the success of Indonesia’s COVID-19 vaccination programme can be a stepping stone for the country to improve its performance in vaccinating its people from other diseases.

“We have two years’ experience in managing COVID-19 vaccinations during the pandemic: we should now have the ability to do more,” he says.