How Uzbekistan scrambled to stay polio-free – and succeeded

Still endemic to neighbouring Afghanistan, polio was suddenly resurging in next-door Tajikistan. Uzbekistan’s health system needed to act fast, or risk the futures of its children.

- 17 February 2023

- 5 min read

- by Umida Maniyazova

Uzbekistan had last recorded a case of polio in 1996, but in 2021, cases of paralytic polio were reported just over the border in Takijistan. WHO declared the outbreak a 'grade 2 emergency,' warning that neighbouring countries "should be prepared and ready to prevent, detect and treat polio cases".

When cases of paralytic polio were first announced in Tajikistan, more than 150,000 children under age five in the Surkhandarya Oblast of Uzbekistan bordering Tajikistan were vaccinated within 11 days.

The news left many Uzbek parents questioning whether the oral polio vaccine given to infants would protect them in the event of a viral importation from over the border. It was a valid concern: the cases in Tajikistan were caused by type 2 poliovirus, a variety eradicated in its 'wild' form, but which can, in very rare and unlucky cases, appear as a mutated version of the safe, weakened vaccine-virus.

In September 2021, the Ministry of Health of the Republic of Uzbekistan announced that it would vaccinate 1.2 million children against polio over the course of ten days. "Infectious diseases know no borders," the Ministry's statement cautioned. For the process, 1.2 million doses of inactivated polio vaccine (IPV) were delivered to the country.

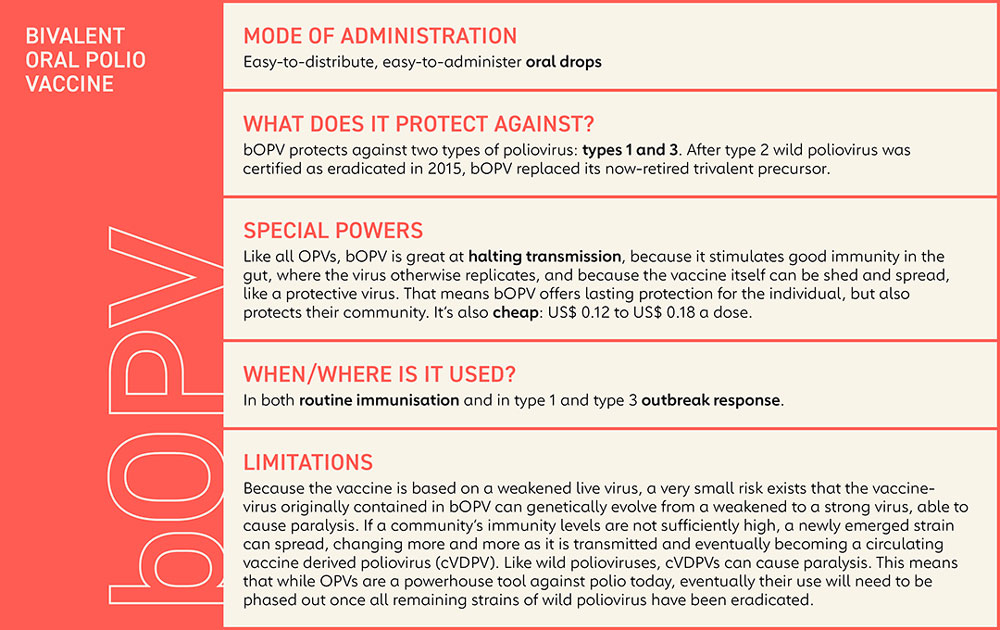

The oral polio vaccine (OPV) is bivalent – protective against polio types 1 and 3, but not against type 2. For that reason, the country introduced additional vaccination with IPV, an injectable polio vaccine that can be used against all three types of poliovirus, explained Dilorom Tursunova, head of the Vaccines and Immunoprophylaxis Department of the Sanitary and Epidemiological Service.

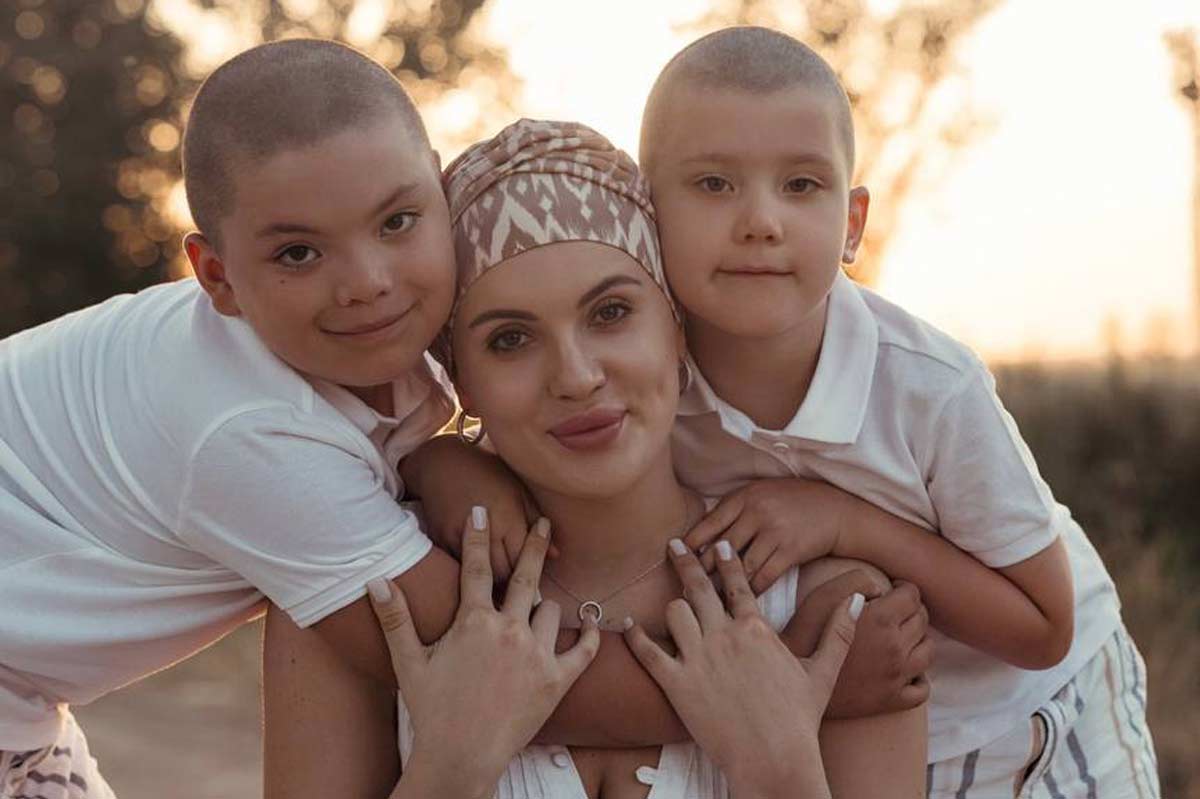

Four-year-old Maksuda from Tashkent received that injected vaccine in September 2021. According to her mother, Sanobar Latipova, the girl has received all routine vaccines under the national calendar, including polio. Therefore, she was surprised at the news that she had to receive the additional inactivated vaccine to reliably protect against infection with the disease. Her surprise didn't stop her: she scheduled an appointment directly.

"At this time, COVID-19 was being distributed in the country, as it was worldwide, but even this did not prevent us from getting the polio vaccine. At first, I thought that a new type of vaccine had been introduced for children, but our family doctor explained to us that several cases of polio had been detected in neighbouring Tajikistan and this made me worried. I took my daughter to the polyclinic the very next day, after we got the call and she got the vaccine. My heart was relieved," says Latipova.

Malika Niyazova, a physician at a family polyclinic in Tashkent city, says: "Some mothers who had young children who were almost a year old or older were too scared to go to the polyclinic to vaccinate their child against polio because of the fear of coronavirus.

Have you read?

"Of course, the process of additional polio vaccination has put an additional strain on the health system at a time when the country is focused on fighting the coronavirus," she adds. "But polio control is no less important, given the consequences of the disease."

COVID-19 and polio are very different illnesses, the doctor clarifies, and equally different vaccines. While COVID-19 vaccines are given mainly to adults, children are the focus for polio immunisation.

Family outpatient clinic health workers called people assigned to their clinic and explained the need for polio vaccination, Dr Niyazova recalls. All necessary precautions were arranged in the polyclinics, to make sure the fight against one infection didn't compromise efforts to halt the spread of the other. To avoid queues or crowds of people, parents were assigned a certain time at which they had to come and get their children vaccinated. In addition, all staff at the health centre wore masks and protective clothing, and all residents visiting the clinic were also required to wear masks.

Routine polio vaccination is included in the national calendar of vaccinations against 13 infectious diseases, according to the Health Ministry. The country uses mixed immunisation – employing both the oral drops and the injection.

According to Dilorom Tursunova, children are vaccinated against the disease in family polyclinics with OPV, an oral polio vaccine, according to the national vaccination calendar. The vaccination process has covered 95-99 per cent of children.

"Continuous monitoring is being carried out to prevent the spread of polio. Measures are also being taken to detect signs of polio in citizens arriving from neighbouring countries," Tursunova says. Afghanistan, Uzbekistan's neighbour along a short stretch of south-eastern border, is one of wild polio's last two remaining endemic strongholds.

In March 2021, when cases of paralytic polio were first announced in Tajikistan, more than 150,000 children under age five in the Surkhandarya Oblast of Uzbekistan bordering Tajikistan were vaccinated within 11 days, she said. Some 300,000 doses of the inactivated polio vaccine were used.

Credit: U.Maniyazova

In addition, to study the epidemiological situation regarding acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) – a condition characteristic of polio, but which can also have other causes – specialists from the Sanitary Epidemiological and Public Health Service (SES) of Uzbekistan visited Surxondaryo Region, which borders Tajikistan and Afghanistan. The specialists provided advice on strengthening the surveillance for AFP at state border sanitary inspection points and health care facilities.

Anvarzhon Yarulin, head of the Sanitary-Epidemiological Welfare Department of Ferghana District, said that here, in one of the most densely populated regions of Uzbekistan extensive awareness-raising efforts were also conducted among residents through TV and radio programmes, so that every family understood the risks of the disease for children. "Before children are immunised against polio, of course, a medical check-up is carried out. After vaccination, the child is under patronage supervision for three days," Yarulin said.

The Uzbek health system's response to this outbreak of poliovirus in neighbouring countries has borne fruit. Not a single case of poliomyelitis has been reported in Uzbekistan.

"As a result of vaccination, since 1996, poliomyelitis caused by wild polioviruses has been eliminated in our republic, and Uzbekistan managed to obtain international certificates called 'Polio Free Territory' in 2002, and 'Territory with 36 months of measles and rubella elimination' in 2017," Nurmat Otabekov, deputy head of the Service for Sanitary and Epidemiological Welfare and Public Health, told a UNICEF press conference last May.