How the West lost its grip on measles (and what we can do about it)

Falling vaccination coverage is promoting a resurgence of measles in countries that had previously eliminated it.

- 8 November 2024

- 10 min read

- by Linda Geddes

In early 2019, a six-year-old boy called Samuel was admitted to a hospital in London, UK, with a rare form of brain inflammation. His family had initially sought medical tests because Samuel had begun to lose his balance while walking. Over the next few weeks, he also started struggling to eat, talk and swallow. By mid-March, Samuel had slipped into a coma. He died six weeks later.

The cause of Samuel’s progressive brain inflammation was measles. He caught the disease when he was two years old and had seemingly recovered, but even people who sail through their infection can develop complications years afterwards. Others develop more immediate problems such as blindness, deafness, ear or chest infections, fits or brain damage.

To many people in the UK, cases like Samuel’s are shocking. “In the pre-vaccination era, we had about half a million measles notifications a year in England, which meant you very likely would have been infected before you turned 10, and these were associated with severe public health burden, with a average 100 measles-related reported deaths a year,” says Dr Alexis Robert, Research Fellow in Infectious Disease Modelling at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

“Notably, the spread of myths and misinformation can lead to a decrease in vaccination coverage and put communities at risk for outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases like measles.”

- Dr David Sugerman, team lead for domestic measles, rubella and cytomegalovirus,Division of Viral Diseases, CDC

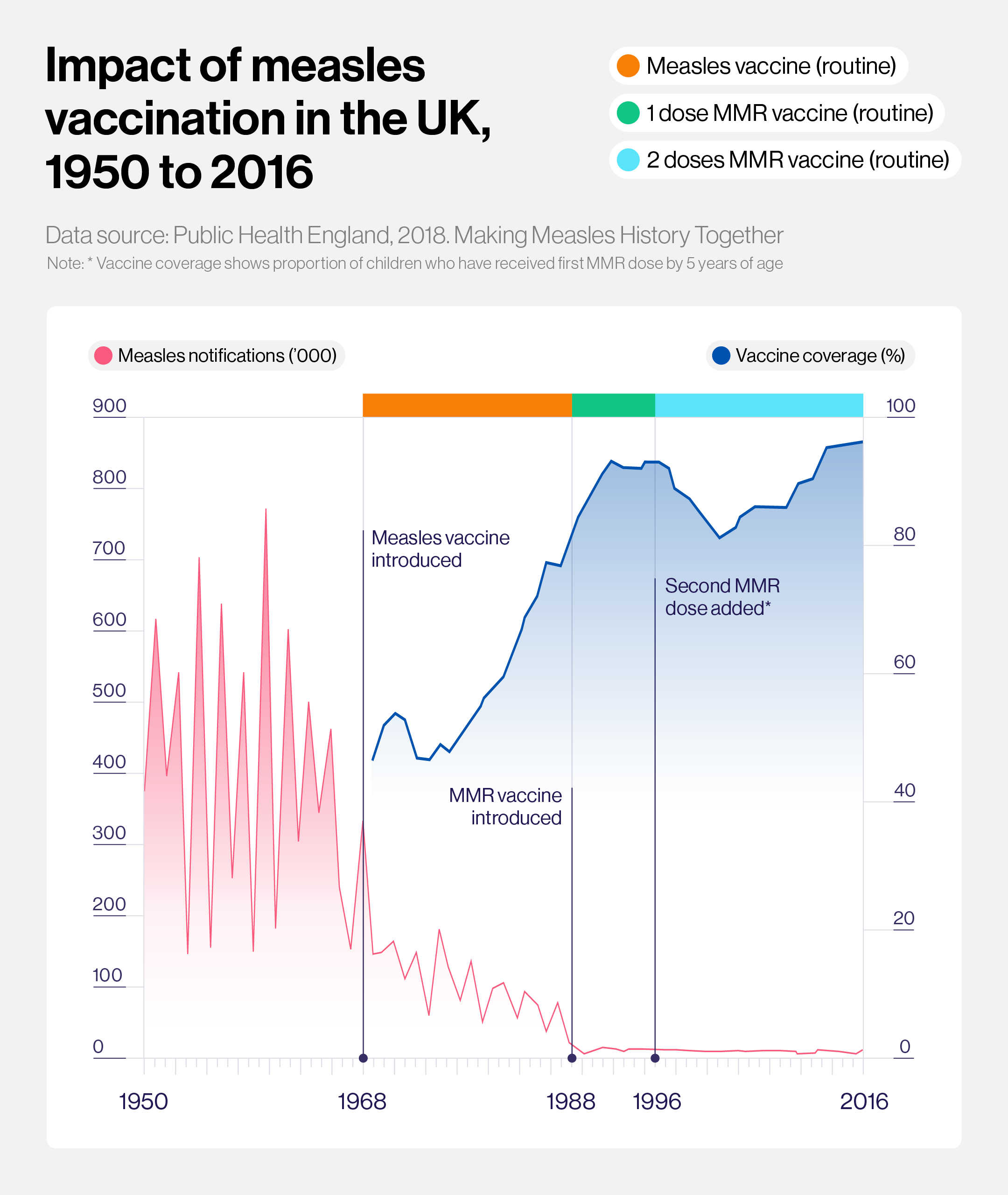

Today though, British babies are routinely offered the measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccine. Since the introduction of mass vaccination in the 1960s, cases of measles have plummeted.

In 2016, measles was officially declared eliminated from the UK, meaning no locally transmitted infections or outbreaks for at least 12 months from the last known case.

But then in 2017, outbreaks in the northern cities of Liverpool and Leeds linked to a resurgence of the disease across Europe heralded the return of locally circulating measles. Despite a temporary lull in infections at the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic and the associated lockdowns and quarantines, the country has been battling outbreaks ever since.

A Europe-wide problem

A similar pattern has been detected in other European countries that had previously eliminated or come close to eliminating measles, such as Belgium and Austria. Between January and October 2023, more than 30,000 measles cases were reported by 40 out of 53 countries in the WHO European Region – a 30-fold increase on the year before.

Four of the five countries with the highest measles incidence were middle-income countries, but high-income countries including the UK, Liechtenstein, Austria, Belgium and Romania have also experienced recent large outbreaks.

“The 2023 measles situation in the European region was particularly alarming, with over 60,000 cases and 13 deaths reported across 41 countries. The majority (98%) of these cases were reported from just 10 countries,” says Cyndi Hatcher, a health scientist in the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC’s) Global Immunization Division.

“In the first three months of 2024, 45 countries reported a combined 56,634 measles cases and four deaths. Provisional data up to August 2024 is showing 98,769 reported measles cases.”

Infections have also been raising concerns in the US, where measles has officially been eliminated since 2000. Although outbreaks have occurred since then – including two prolonged outbreaks among an under-vaccinated community in New York in 2019 – the country has maintained its elimination status by rapidly stamping them out and ensuring overall high measles vaccine coverage.

However, in response to a spike in infections detected during the first quarter of 2024, the CDC said additional activities were needed to increase routine MMR vaccination coverage, especially among close-knit, under-vaccinated communities and those planning international travel.

Measles-containing vaccines are one of the most effective public health interventions going, with two doses providing almost 100% protection against measles. High-income countries have ample access to doses, as well as health systems that should be well-equipped to deliver them into babies’ arms.

Yet, through a combination of biology, sociology and politics, many such countries appear to be losing their grip on measles, with implications for the wider world.

Herd protection

Samuel’s mother wasn’t anti-vaccines, but Samuel didn’t receive the MMR jab as a baby because he had been experiencing constant chest infections – which later turned out to be asthma – and his doctors recommended waiting.

In countries with high vaccination coverage, a phenomenon called herd immunity should mean that individuals who can’t be vaccinated, like Samuel, are still indirectly protected, because the measles virus can’t find anyone new to infect. For measles, herd immunity kicks in once 95% of the population has received two doses of measles-containing vaccine.

The UK has never managed to achieve this level of coverage, but it has come close: Scotland hit 94% coverage between 2013 and 2016. Thanks to these ongoing vaccination efforts, few Britons have ever met someone who had had measles.

Yet, several factors have led to a backsliding in vaccination rates in recent years.

“Many factors influence vaccine decision-making, including cultural, socia, and political factors. Notably, the spread of myths and misinformation can lead to a decrease in vaccination coverage and put communities at risk for outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases like measles,” says Dr David Sugerman, team lead for domestic measles, rubella and cytomegalovirus in the CDC’s Division of Viral Diseases.

“The CDC is addressing vaccine uptake and combatting misinformation around the MMR vaccine through education, including providing reliable, evidence-based information to the public through a variety of platforms including the CDC website and our Keeps It that Way campaign, focused on childhood vaccination.”

Increased questioning about the safety or importance of vaccines, as well as a lack of knowledge or trust in health care, are also consistent themes in the UK. However, these are not the only issue.

“Many countries in Europe have a high vaccine coverage, but they will [also] have areas or groups with lower coverage and if the measles virus gets there, then there's going to be an outbreak. Because measles is so infectious, we need to have a high vaccine coverage, but we also need to have homogenously high vaccine coverage if we want to control transmission.”

- Dr Alexis Robert, Research Fellow in Infectious Disease Modelling at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine

For one thing, a restructuring of how vaccination services are delivered by the health system has made it harder for some people to access vaccines. As well as doctors’ surgeries, in the past many community-based ‘Children’s Centres’ ran vaccination clinics.

Because parents were already going there to receive different types of support or to attend parent and baby groups, getting their child immunised was convenient. However, reduced funding has led to the closure of most of these centres.

“That kind of convenience and supportive, enabling environment for immunisation has been taken away, with the focus now very much on primary care and going to your GP surgery for vaccinations, when these services are also overstretched,” says Dr Ben Kasstan-Dabush, assistant professor in global health and development at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine.

The drive for austerity has also changed the role that health visitors – who provide targeted support to vulnerable families in their homes – play in immunisation, including reducing the amount of time available to discuss it with parents.

“Funding cuts mean that the current asks of health visitors when they go in are just huge, and vaccination is one of multiple things we are expected to talk about. Even if we manage to, whether it is heard by parents is another thing,” says Amy Campbell, clinical lead for health visiting in Bristol, UK.

Although some of these factors are UK-specific, austerity is not: “I think it has probably characterised the past decade in lots of countries and societies,” says Kasstan-Dabush. “And I would hazard to guess that it has reconfigured the ways that systems invest in public health and immunisation – whether that’s the funding available for the ‘where’ of vaccination or the ‘how’ of communication about vaccines.

“These things are crucial when you're working with underserved communities and those who may need additional support to participate in a routine immunisation programme.”

Reduced protection

Although coverage with two doses of measles-containing vaccine is still well above the global average of 74%, immunisation rates within the UK are slipping.

By 2022/23 the proportion of children receiving two doses of the MMR vaccine by their fifth birthday had fallen to 90% in Scotland and 84.5% in England. However, within these figures there is also significant regional variation. For instance, while coverage in the north east of England stood at 90.4%, in London it was just 74%.

Even in countries where measles has been eliminated for a number of years, outbreaks can occur in under-vaccinated communities, if someone who is infected with measles arrives from abroad.

For instance, a measles outbreak in New York City, which resulted in 649 confirmed cases between September 2018 and July 2019, started when a single unvaccinated child returned home from Israel with measles.

“Many countries in Europe have a high vaccine coverage, but they will [also] have areas or groups with lower coverage and if the measles virus gets there, then there's going to be an outbreak,” says Robert. “Because measles is so infectious, we need to have a high vaccine coverage, but we also need to have homogenously high vaccine coverage if we want to control transmission.”

This risk of measles importation is a key reason why some public health experts are calling for a global target for measles elimination.

“Almost all countries really struggle to sustain their achievements when the virus is circulating elsewhere in the world,” says Dr Jon Kim Andrus, chair of the Pan American Health Organization’s Regional Verification Commission for Measles and Rubella Elimination.

As the world moves closer to measles elimination, outbreaks in high-income countries could also potentially seed infections in lower-income countries, where the consequences of catching measles are even more serious.

If you’re healthy, well-fed and live in a wealthy country, your chances of dying if you catch measles are 1 in 1,000. But some epidemics in poor countries have recorded fatality rates as high as 15%.

“Given the frequency of travel to and within Europe, the risk of importation is substantial, and we must remain vigilant, even in countries that have eliminated measles or are close to achieving elimination,” says Hatcher.

Countering the threat

Reversing these trends will not be easy. In both the UK and US, catch-up campaigns have been launched to get young people up to date with their vaccinations. NHS England is also experimenting with new models for delivering vaccinations, including health visitors taking on some of these responsibilities.

“The untapped potential of health visiting on vaccination is huge,” says Campbell. “Many of the families that we see aren’t even registered with a GP; they don’t have an NHS number. They might be from traveller and Roma communities, newly arrived in the UK, non-English speakers or families who do not currently access other health information and support. So there is a huge amount of untapped potential regarding access, early intervention and building trust with families for any public health topic ˜ immunisation included.”

Meanwhile, Kasstan-Dabush has been involved in evaluating targeted outreach initiatives to try and boost vaccine uptake in London’s ultra-Orthodox Jewish community.

“This has included having vaccinations on offer as part of family fun days, alongside free toothbrushes for oral health, and diet and nutritional advice,” he says.

While it may not be possible to offer this as a standard service, “it is part of that bigger picture of a creating family-friendly service.”

Tailored interventions that make it easier for under-vaccinated or marginalised communities to access vaccines or to discuss vaccination are also helping to increase uptake in other areas of the world, including India. However, it is essential that such initiatives are adequately funded, if they are to work.

Also necessary will be ongoing efforts to counter vaccine misinformation, including claims that measles vaccination is associated with autism – a claim that studies have repeatedly disproven – or that it doesn’t matter if a child catches measles. As Samuel’s death illustrates, measles still has the potential to shatter lives, no matter where in the world you live. But thanks to vaccines, it is entirely preventable.