Measles: a VaccinesWork briefing

This week VaccinesWork is spotlighting measles: super contagious, damaging, deadly – and always more destructive amid poverty. Stick with us to find out about this horrific, yet eminently preventable, disease and the global effort to contain it.

- 4 November 2024

- 4 min read

- by Maya Prabhu , James Fulker

Later this month, WHO and CDC will release their annual global measles statistics. We’re hoping deaths will be lower than last year’s figure of 136,000 – but we can bet they will be higher than they should be.

That’s not because measles isn’t dangerous. With an R0 figure of 18 – that’s the number of people each sick person is expected to infect – it’s one of the most contagious human viruses we know. Walk into a room two hours after a measles patient walked out and, unless you’ve been vaccinated or had measles before, you’re liable to catch it.

What happens after that is a big, tragic case of it depends. If you’re healthy and well-fed and live in a wealthier country, the chances that you’ll pull through are very high: about 999 in 1,000. That still leaves, of course, a 1 in 1,000 chance you’ll die, typically as a result of a secondary infection that sets in when the measles virus brings your immune system to its knees.

For several reasons – nutritional status is a big one, but there are others, like the likelihood of receiving a larger infectious dose if you live in a crowded setting with plenty of virus circulating – your odds get steeply worse if you live in poverty. Some epidemics in poor countries have recorded fatality rates as high as 15%.

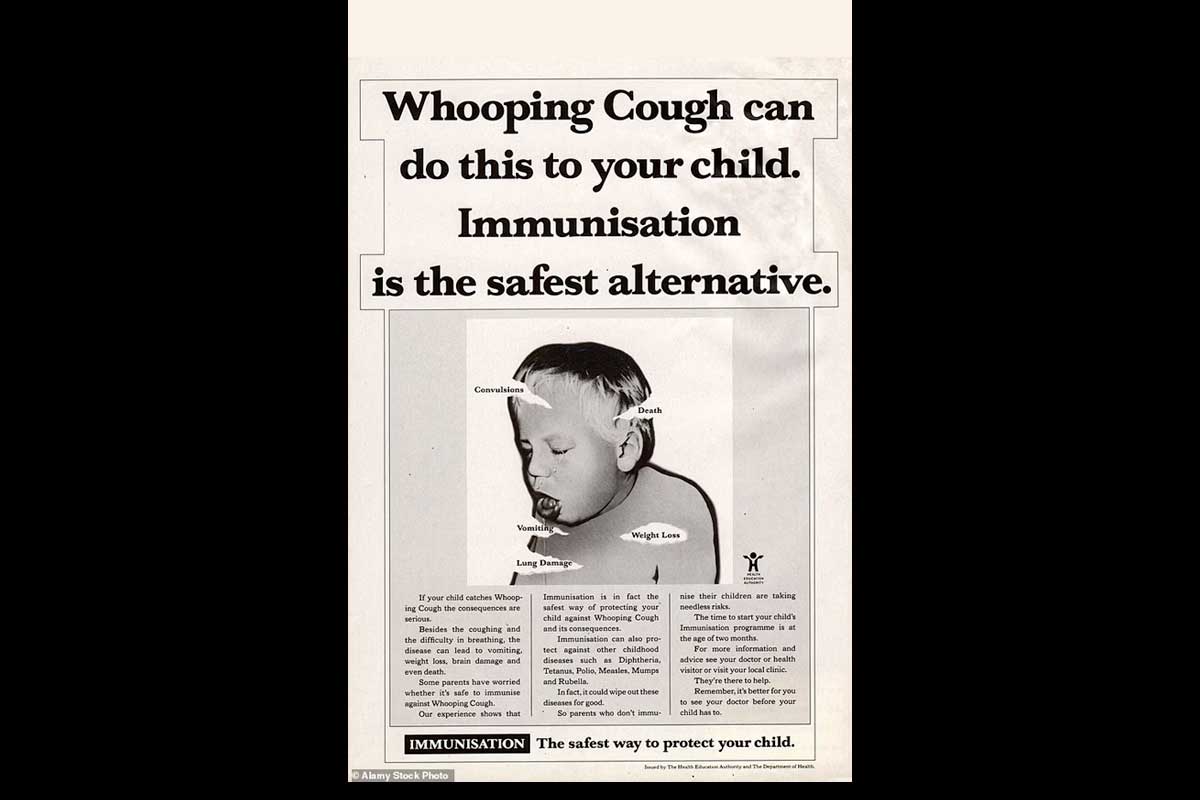

And, brutally, survival doesn’t always mean recovery. Just 20 years ago, measles was the single leading cause of childhood blindness in poor countries, and it still causes children to lose their vision today.

Measles-linked hearing loss is likely under-reported. Measles-precipitated encephalitis has been known to leave survivors with a dizzying spread of neurological deficits, from seizure disorders to paraplegia to intellectual disability.

Rarely, an apparently cleared measles infection can hide out in the brain, and boomerang years later as a disease called sub-acute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE), which starts subtly – headaches and forgetfulness are among typical early symptoms – but ends, always, in death.

And measles can rob the immune system of its protective memory of other pathogens, leaving children more vulnerable to other illnesses for years after they recover.

But the vaccines we have are outstanding. Two doses of the measles jab are close to 100% protective, which means, simply put, that vaccinated kids are safe. And if 95% of a population is vaccinated, then the herd immunity threshold is achieved, and everyone is safe.

So why are people still dying of measles? At risk of being infuriatingly circular in our answer: because too few people are vaccinated. The immune gap grew during the COVID-19 pandemic: in 2019, 86% of eligible children had received their first dose of the vaccine. In 2023, that rate stood at 83%.

Let’s be clear: we’ve travelled lightyears. Before the measles vaccine existed, the virus killed an estimated 2.6 million people a year. Between 2000 (not coincidentally the year Gavi was established) and 2022, the World Health Organization estimates that measles vaccination staved off 57 million deaths. It’s been so effective in some countries that entire measles wards have been permanently shut down.

But although the measles death toll for 2022 was less than a fifth of what it was back in 2000, it was still 136,000: way too many. This is why Gavi is currently fundraising for its next five-year period, from 2026–2030. Raising the full US$ 9 billion we are asking for means expanding access to these lifesaving vaccines to millions more children in the world’s most vulnerable countries.

The fightback is well underway. Stick with us this week to learn about big, ambitious immunisation campaigns, compelling innovations, and just how reasonable it is to hope for elimination in the nearish future.

For now, we’ve pulled up some of our favourite measles stories from the archive for you.

Anatomy of an outbreak: measles hits urban India

Measles ripped through Thane, near Mumbai, after immunisation coverage dipped during the pandemic. VaccinesWork visited the city to hear about its devastating impact, as well as how social factors may have helped its spread.

South Sudan’s nationwide anti-measles campaign pays off

Awerial County’s vaccine blind spots included cattle camps and a remote lake island, but April’s ambitious mobile outreach efforts have calmed the early year’s spike in cases.

“I will never forget”: a father in Pakistan recalls almost losing his baby to measles

Massive vaccination drives against the virus have made headway in Pakistan. But for the unvaccinated, the risk remains grave.

After measles, a life in the dark

Not so long ago, measles was the leading cause of childhood blindness in poor countries. Vaccination and vitamin A supplementation helped – but now measles cases are again on the rise. In Ethiopia, VaccinesWork spoke to sightless survivors.

History: finding a vaccine against the measles

How the measles virus was trapped and tamed in vaccinology’s wild West.

More from Maya Prabhu

Recommended for you