Last Mile Delivery: How Borno State is reaching children in conflict zones with routine immunisation services

Maina Modu is the programme manager for Routine Immunisation in Borno State, working with the State Primary Health Care Development Agency (SPHCDA). He coordinates the state emergency routine immunisation coordination centre activities.

- 15 February 2021

- 13 min read

- by Nigeria Health Watch

Maina Modu is the programme manager for Routine Immunisation in Borno State, working with the State Primary Health Care Development Agency (SPHCDA). He coordinates the state emergency routine immunisation coordination centre activities.

For those safe areas we have a direct vaccine delivery system in place where our vehicles can convey the vaccine from the zonal post to the individual health facilities, but for the security compromised areas we have a plan for the LGAs to come and collect their vaccine

Borno State’s routine immunisation emergency coordination centre is nestled at Maiduguri’s Maman Shuwa Memorial Hospital, in the Polio Emergency Operations Centre (EOC). Modu and his team work with partners and the state to ensure that routine immunisation (RI) continues to happen in the state. They coordinate logistics, service delivery, and community engagement activities.

Modu said his team has targets on how many children under 1 year of age they are meant to reach with immunisation services annually. “The administrative target shows that we are supposed to reach up to 265,168, but what is on ground is far far beyond that. If you look at our coverage like in November last year, we reached up to 90% but still a lot of children were not reached in some areas,” he said.

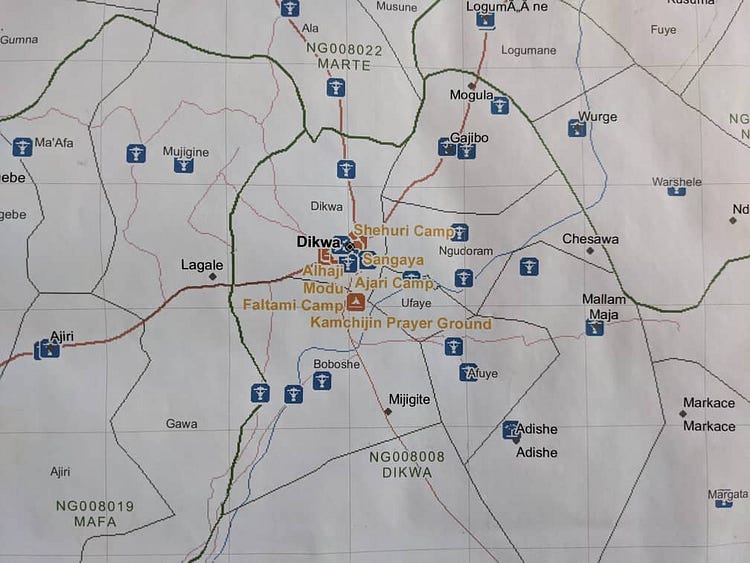

Some of the areas where the RI team is unable to reach children are places cut off by the current insurgency in the North East, such as parts of Dikwa Local Government Area (LGA). Dikwa LGA is east of Borno State and has ten wards. The LGA was once controlled by non-state armed groups (NSAGs), known as Boko Haram, in August 2014 but was recaptured by the Nigeria army in June 2015. The LGA capital Dikwa town lies some 90 km away from Maiduguri and is a gateway to several other LGAs, including Bama, Ngala, Mafa and Marte.

Over the years of the insurgency in North East Nigeria, the abduction of women and girls, destruction of towns, the killing of hundreds of innocent civilians, and large-scale displacement has been reported. Livelihoods have been devastated and assets looted. Although the Nigerian military regained control of Dikwa, travel by road to Dikwa from Maiduguri is only feasible with military escort. Nine of the ten wards in Dikwa LGA are inaccessible to humanitarian partners due to insecurity. The humanitarian response is therefore limited to the people in Dikwa town, who are dependent on humanitarian assistance due to lack of livelihood opportunities. Most of the internally displaced persons (IDPs) are farmers from the inaccessible neighbouring villages and LGAs. Dikwa has 17 IDP camps that are managed by the International Organisation for Migration (IOM) and Agency for Technical Cooperation and Development (ACTED). High congestion across the IDP camps has degraded the quality of services provided in the camps. This is a result of IDPs self-settling in between the already planned shelters.

The inaccessibility of most of Dikwa LGA and other LGAs in conflict-affected areas is a huge concern for development agencies working in the region and the state agencies set up to provide healthcare services, like the SPHCDA. Modu admits that the insurgency has made the state’s routine immunisation service delivery challenging.

Have you read?

“Right now, we operate in 377 out of the 672 existing health facilities,” he said. “This limitation is due to the security challenges we have which has affected the routine immunisation approach in the state.” He notes that prior to the insurgency the state already had challenges with routine immunisation service delivery, both on the side of supplying vaccines and generating demand for immunisation services.

Fortunately, in 2015, the state signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF) and The Aliko Dangote Foundation (ADF), which helped the state begin to address the supply side challenges. The MOU was to help revamp the routine immunisation system. “In the first year of the MOU, the state was to contribute 30% while the two principal partners provided 70% of the budget,” Modu explained. In the second year, the state’s portion of the funding increased to 50%, and in the third year the state was to provide 70% of the funding. The MOU was initially meant to end in 2018

They channeled the funds towards vaccine logistics, including the procurement of Solar Direct Drive (SDD) Refrigerators to store and distribute the vaccines and outreach services across all the health facilities. “We are funding each of the 377 health facilities to conduct four outreach services per month,” Modu said, adding, “We disburse these funds directly from the state to the health facilities quarterly. We also have funding for monthly review meetings to review the performance of activities with the health facility workers.”

The funding from the MOU is also used to get communities on board with the state’s routine immunisation drive, and train health workers. “We fund the community engagement aspect where we engage the Bulamas, the Lawans and the district heads to ensure they can enlist their under 1 aged children in their domains. We also fund the training of our health workers in routine vaccine introduction,” Modu said.

Adapting cold chain storage in the midst of insurgency

As a result of the insurgency, the MOU between the state and the two principal partners was extended till 2021. “Dangote Foundation and BMGF are providing 30% of the funds while the state government is providing 70% till 2021,” Modu explained.

For routine immunisation activities to continue in conflict-affected areas, ensuring that the cold-chain logistics remain in place is crucial. “At the peak of the insurgency we were able to provide SDDs across the state,” Modu said, but added that in some LGAs security challenges began to increase between 2014 and 2015, affecting government health infrastructures.

The state’s goal was to provide one SDD to each of its 311 wards, but the humanitarian crisis meant the state had to look at other ways of ensuring that the cold chain for vaccines is provided. “If you look at the case of Dikwa, Dikwa is only one ward that’s hosting all the IDPs in Dikwa and you know the criteria is to give one SDD per ward,” Modu explained. “We are trying to ensure that the other devices we have for storage reach to health facilities and then the SDD will only be installed in Dikwa.” He pointed out that the health facility where the SDD will be installed must be a government health facility. Other health facilities would then come there and pick up their vaccines.

“We deploy the SDDs where the security situation is stable,” Modu said, adding, “In most of the conflict affected LGAs we have to ensure we deploy devices that can keep our vaccines. Like now in Damasa, we were able to go and install one SDD there to ensure that vaccines are available. Then there’s also a new device, an indigo device, that can keep our vaccines. It does not require much maintenance. If you charge this device, it can last for at least 10-15days. So, we are trying to deploy such devices to the security compromised areas to ensure that vaccines are available in those locations.”

According to a blog on vaccination innovations by Bill Gates in 2018, a group of inventors called Global Good created the Indigo Cooler. The cooler keeps vaccines at the right temperature for at least five days with no ice, no batteries, and no power required during cooling.

Modu said the state is working towards deploying the indigo cooler for RI activities after they experienced its benefits in supplementary immunisations. “It is a friendly device, just like a vaccine carrier and having the required temperature for storing vaccines. So we are working with a partner to ensure that all our health facilities located in the security compromised areas are provided with the indigo vaccine carriers,” he said, adding, “If we have devices like indigo, they can collect their vaccines for a week or two weeks and then keep it in their facilities before having to report back to the apex health facility.”

To ensure that SDDs and other storage devices can get into conflict zones, the Borno PCHDA enlisted the help of the Nigerian Military. “We also use the support of military to convey these devices to station our routine immunisation activities in conflict areas, especially Dikwa, Kala Balge, in Monguno, because of the destruction by this insurgency of our infrastructure,” Modu said, adding that “In a town like Dikwa for instance, we operate only in 4 health facilities out of which only two are government health facilities. The other two apart from these, Disanga IDP camp and the ICRC clinic, are all supported by humanitarian agencies.”

Meeting the demand for RI services in conflict zones

In 2021, two additional health facilities will likely be supporting immunisation service delivery in Dikwa. “Throughout 2020 we are operating only in 4 health facilities and you can see the huge population concentrated in Dikwa. Now we understand that Intersource is also willing to commence routine immunisation in Dikwa and the current Dikwa dispensary has been renovated, so they are about to start as well,” he said. The Dikwa Dispensary was renovated by a private sector partner, and primary health services were also expanded through the construction of a 20-bed facility, and provision of a deep solar-powered borehole to the PHC.

The increased demand for RI services in Dikwa and other towns where IDPs have fled for refuge prompted Modu’s team to make changes to the immunisation days at the existing facilities. “For us to reach out to more children we need to optimise our sessions, so we asked those health facilities to conduct daily fixed immunisation sessions and then also at least 4 outreach sessions per week to meet up our target,” he said.

Generating demand for RI services in places like Dikwa has not been difficult, Modu said, because caregivers living in the IDP camps are “always eager to accept whatever the government is bringing.” He said the challenges that arise come when some mothers become non-compliant to routine immunisations because the health workers’ offer does not appear as attractive as the package given by humanitarian agencies. “Sometimes they may react to say ‘you’re giving us routine immunisation all these times but you’re not bringing anything like other organisations who are giving us money, non-food items, and food items’,” he said.

Community engagement with the traditional institutions has also proven to be key for generating demand and building sustainability into the RI program. The state engaged the Emirs and Lawans as part of the strategy to foster ownership and support for the program. Modu said some traditional leaders came to expect to be paid to carry out their duties as a result of the influence of humanitarian agencies, but continued advocacy to the traditional institutions has helped these leaders see that supporting this program is their responsibility.

Distributing vaccines safely to conflict-affected zones

Most humanitarian workers coming into Dikwa and other conflict-affected areas from Maiduguri arrive by helicopter, a service provided by the United Nations Humanitarian Air Service and managed by the World Food Programme (WFP). Modu said vaccines are delivered to conflict areas by road with military escort, and where that is not possible, by helicopter.

The state distributes vaccines through zonal storage facilities, one in Maiduguri to cater to the central zone and one in Southern Borno to take care of the nine LGAs in the South. “For those safe areas we have a direct vaccine delivery system in place where our vehicles can convey the vaccine from the zonal post to the individual health facilities, but for the security compromised areas we have a plan for the LGAs to come and collect their vaccine,” Modu said. “We do that monthly and we pay transportation for conveyance of vaccines to those LGAs.”

He said the major challenge they face in distributing vaccines is the “delay in movement of vaccines from the state to the LGAs. Because we need to have security clearance from the military who will convey vaccines to those locations. And even if the LGA is to come and collect the vaccine at the state level, we need to have a clearance for the LGA to collect the vaccine and convey to their LGA.”

Most of the LGAs in Borno affected by the insurgency are in the north and central zones of the state, and in order to ensure that vaccines get to these areas, Modu said the state disburses monthly stipends of N10,000 to the LGA Cold Chain officers that come to Maiduguri to collect their vaccines.

Dealing with human resource challenges

A significant number of the health workers providing services in conflict-zones like Dikwa and environs are employed by partners providing humanitarian services at health facilities. When partner programs end, they disengage their personnel, and where there is no sustainability plan built into the program, it results in a dearth of skilled health workers.

“If we discover such challenges, we quickly deploy health workers to those locations to provide routine immunisation services,” Modu said. “In Dikwa I think we deployed three of such individuals to provide services. We have them across the state in the conflict-affected areas.” He said the state has currently deployed about 100 health workers to support routine immunisation services. He added that health workers recruited to fill human resources for health gaps for routine immunisation services are paid N20,000 per month, and when the state is planning to engage new health workers, this pool of workers are first to be deployed. “That is how we motivate our health workers to provide services in some areas,” he said.

Charting the path ahead

Modu says he is proud of the commitment and sacrifice that the frontline health workers and his team have made to continue providing RI services despite the security challenges facing the state. “A lot of us in Borno, be it partners, state or LGA staff, have all faced a lot of challenges, but we insist that we would not stop the fight until we reach out to all eligible children,” he said.

He says the state has the necessary structures in place for routine immunisation but is quick to point out that the drivers of success for the program in the state has been the MOU with the Dangote Foundation and BMGF. That agreement is set to end this year, although the state is considering extending the MOU to a broader range of primary health care services, Modu said.

To move forward, Modu is eager to see the state PHCDA established and Primary Health Care Under One Roof (PHCUOR) become a reality in Borno. “As I am speaking to you now the SPHCDA has no budget, has no overhead, but because of the synergy with partners, that’s why most of our activities are moving as a state,” he said, adding, “So, my prayers is to have PHC Under One Roof in Borno State. That will move us forward.”

Author

Adaobi Ezeokoli

Ada is the Editor of Nigeria Health Watch. She has a B.A. in Communications - Journalism and Creative Writing, and an M.A. in Ancient Near Eastern History. She is a documentary photographer. She tweets as @adankemeze.

Website

This article was originally published by Nigeria Health Watch on 9 February 2021.