Rethinking healthcare in Africa with geospatial mapping

In August 2020, Nigeria became the last African country to be declared free from wild poliovirus.

- 23 December 2020

- 5 min read

- by Nigeria Health Watch

In August 2020, Nigeria became the last African country to be declared free from wild poliovirus. This was achieved by relentless vaccination efforts across urban and rural communities, including awareness campaigns and deployment of personnel to communities to carry out vaccination programmes. An underlying, but essential enabler of this success story was the use of location technology to carefully map out areas where there were outbreaks, and that were most in need of these vaccines. The technology combined mapping software capabilities and mobile devices to capture, analyse and present data as legible and informative maps, as against the hand drawn maps that were previously in use.

Where else has location technology excelled?

In 2019, Kaduna State released the Kaduna State Health Facility Census Report and Interactive Analytics (HEFA). The HEFA project was aimed at clearly understanding the state of healthcare facilities and access to healthcare services, to ensure effective planning and service delivery. Simultaneously, it provided baseline information on the capacity of healthcare facilities to provide basic care, as well as the record-keeping systems in place to monitor, prevent and diagnose infectious diseases.

Using a combination of questionnaires and GPS coordinates, about 5263 public and private healthcare facilities were enumerated, with issues like no government facility below secondary level having a phone line and shortage of HIV/ARVs in private facilities being identified. The findings from Kaduna show us the promises that the use of robust data in healthcare holds; how it can help decision makers solve the most important problems, ease the work of public health workers, as well as inform lawmakers on the right allocation for health budgets.

The census that has been carried out in Kaduna will become obsolete in a few years as the population grows and as the dynamics of survival evolve. This is why there is an enormous need for big data and automation to run full course in the healthcare sector in Nigeria, so as to sustain the gains of states like Kaduna.

Have you read?

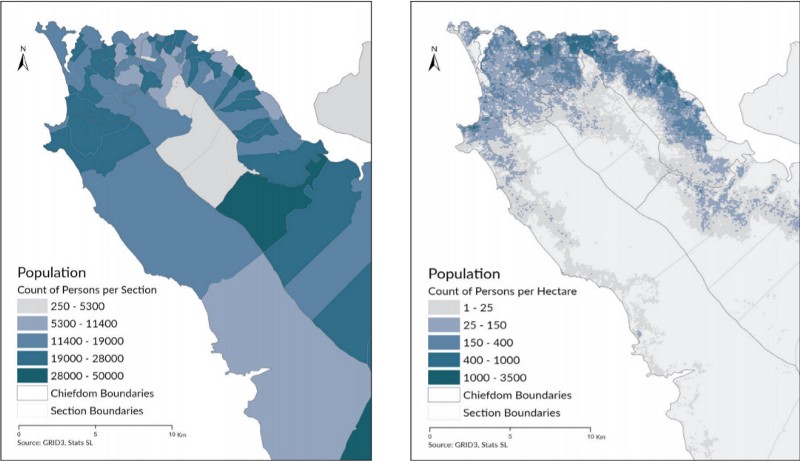

In some countries across Africa, the outstanding response to the COVID-19 pandemic has had the use of location technology in play as the virus moved progressively from country to country. In Sierra Leone for instance, the COVID-19 response team did not only consist of healthcare workers and policy makers, the Directorate of Science, Technology & Innovation (DSTI) as well as Sierra Leone’s statistical body came together to produce crucial geospatial datasets that helped track the spread of the virus. The estimates, which provide demographic data as well as the risk level of populations and their socioeconomic vulnerability, have been described as the most granular in Sierra Leone’s history.

In South Africa, GIS-powered contact tracing apps that track infected people and notify those who were in close proximity to them during the past 15 days were developed. A combined effort of the South African government, National Institute of Communicable Diseases (NICD), the country’s centre for communicable disease, a research institute as well as private technology players led to the development of the vulnerable communities map which provides demographic data, state of healthcare, mobility level as well as poverty levels in communities across South Africa.

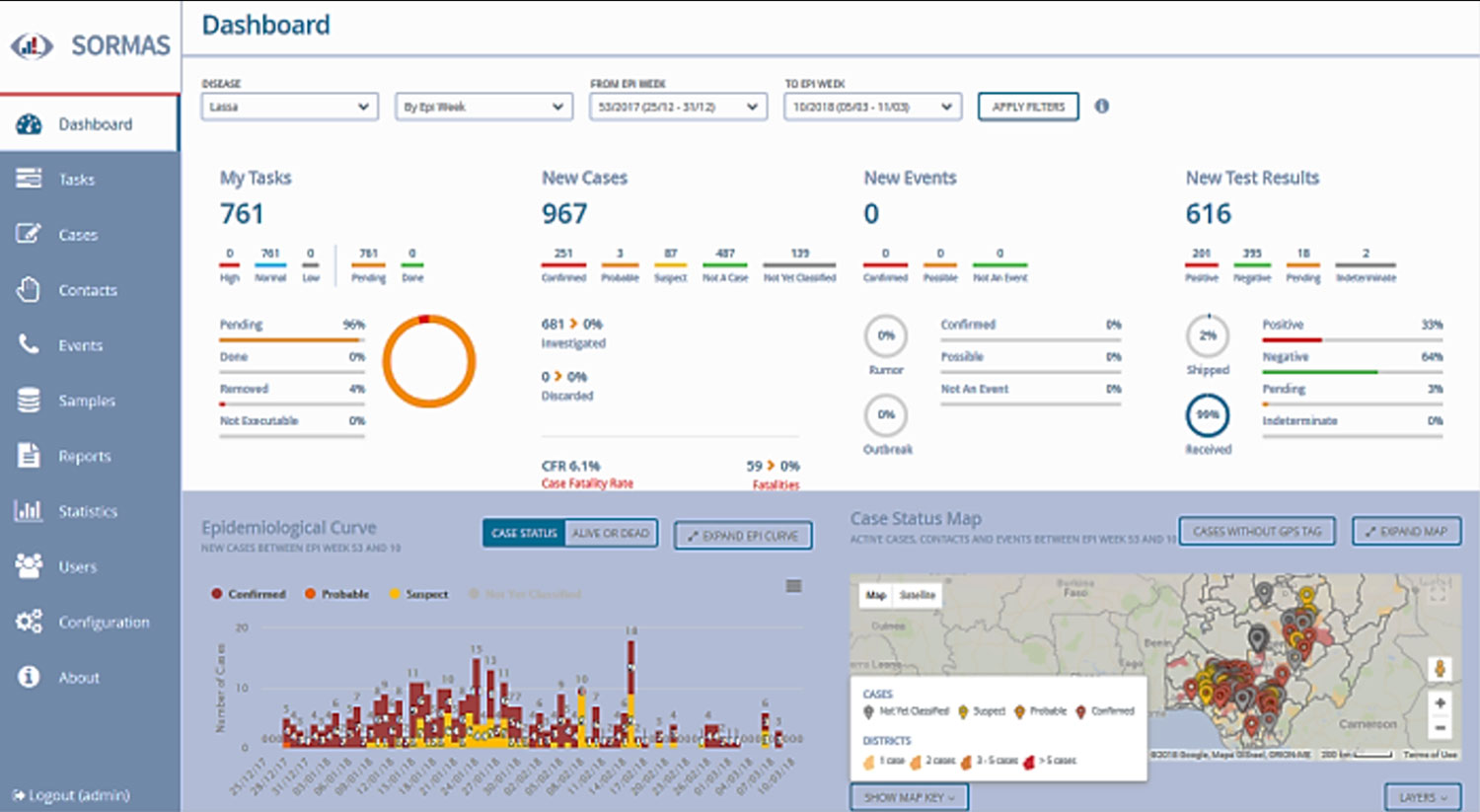

In Nigeria, a Surveillance Outbreak Response Management and Analysis System (SORMAS) which combines location (health facility) data and contact tracing has been deployed as part of COVID-19 containment measures. This system which is also being used to track monkeypox, meningitis and the Lassa fever outbreak has been deployed in 196 Local Government Areas in 12 states, including the FCT since 2018.

Why we must get data right

Big data provides a huge opportunity for Africa and Nigeria in particular to improve medical surveillance. However, reliance on non-digital methods of collecting patient information makes it difficult for this advancement to occur. For Dr. Pelumi Olaore, Special Assistant to the Kaduna State Governor on Primary Health Care, we need to end our reliance on data from outside.

“The paucity of data in Nigeria often leads to making treatment decisions and interventions based on research conducted abroad. This does not always yield the best outcomes as the environment is different and as such may require a different approach. For example, hypertensive heart disease is gradually becoming prevalent amongst the younger age group in Nigeria and the lack of research/data to help identify the cause has led to an increased incidence of strokes in middle-aged men and women. To reverse these trends, we urgently need to start conducting research and generating data locally,” he said.

While we have made remarkable gains in tracking the COVID-19 pandemic, it is important to track other outbreaks like Lassa Fever which has been a silent pandemic across many states in the country. Funding health research and digitising public healthcare facilities must become a priority area for government and key stakeholders.

What can we do for a change?

The increasing need for humanitarian aid, especially in the northern part of Nigeria, makes it an even more urgent need, but despite several attempts to provide reliable geospatial data, a significant information gap remains in this area. From all the instances we have seen, the most common success factor is not just the application of technology, but collaborations across several levels in the public and private sector. In Nigeria, alliances between government agencies and the private sector appear to be dwindling, making it difficult to solve its major challenges.

This lack of accord is also reflected in the way information or data is being shared between government agencies and departments, as well as the private sector. Moving forward, it would be ideal for harmonisation of data to occur across various levels of the public and private sector.

Organisations that have funded different kinds of geomapping projects can come together and create a unique map of the most vulnerable populations within the country to facilitate prompt health response and to ensure that no one is left behind, on the path to achieving good health and well-being.