“My heart is always stuck in my homeland”: A Rohingya returnee’s story

Abdullah and his family escaped genocidal violence in Myanmar in 2017, survived a diphtheria epidemic in Bangladesh’s Cox’s Bazar and weathered the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic in a Rohingya camp. Then, in December 2020, he returned to the country that forced his flight. He tells VaccinesWork his story.

- 29 July 2021

- 9 min read

- by Maya Prabhu

A few months after he swam back to Myanmar from Bangladesh, Abdullah and three of his friends drove out to the spot in Maungdaw District where his village used to be. It was the day of Eid, May 2021, and he wanted to read a prayer for the dead in the cemetery. As far as the living were concerned, the place was desolate. The houses had been burnt down the day Abdullah’s family left nearly four years earlier, and now the jungle was staking its claim. There was evidence that a herd of elephants had moved in; Abdullah suspected that “different kinds of snakes” were living in the overgrown graveyard.

The proportion of humanity forced to flee their homes and seek safety elsewhere has been rising, hitting new records every year for the last nine years.

It wasn’t the return he had dreamed of during his refugee years. Abdullah, now 26, numbers among the 700,000 Rohingya Muslims who fled their homes in Rakhine State for Bangladesh in 2017 when the Myanmar army unleashed a campaign of genocidal violence . It had begun decades earlier: since the 1970s, the Rohingya minority have been subject to discriminatory policies in the mostly Buddhist country, including an official denial of their status as one of Myanmar’s ethnic groups, meaning that they are considered illegal immigrants from Bangladesh even when their roots in Myanmar are centuries deep. But in August 2017, a fresh offensive of killings, rapes and village-razing triggered an unprecedented exodus of the persecuted.

On 25 August, 2017, Abdullah was at work, teaching in a high school about seven miles from his home, when “the military started burning my village – at that time, not only my village, but two other villages as well.” He reached his mother on the phone. “My mother told me that they are leaving”: on foot, en masse, for the border. She urged him to hurry and find them. He caught up with them – his mother, his grandmother and his brother’s family, amidst a trudging column of frightened neighbours – halfway through the first day of the two-day walk to the river which divides western Myanmar from south-eastern Bangladesh. His brother’s three children were little and needed to be carried. “We became very tired,” he says. They jettisoned most of their luggage on the roadside.

At the river, Abdullah learned that the going rate for a boat to escape Myanmar was about 200,000 kyat (approximately US$ 120). Many couldn’t afford it. Even for those who could, the danger wasn’t over: a Reuters report found that 196 people drowned fleeing Myanmar between August and November 2017. The boat behind Abdullah’s family’s in their convoy of three, sank. “There were 21 people at that boat. We found only 11 people,” Abdullah says. “The other ten people – we didn’t find them.”

(UNICEF/UN0119963/Brown)

A previous wave of persecution in Myanmar in 2012 had displaced an aunt named Yasmin, who welcomed them that night in her tarpaulin shelter in a sprawling Rohingya camp in Bangladesh. “My auntie cooked rice,” Abdullah remembers. They hadn’t eaten a proper meal since the burning began, and had drunk only muddy canal and river water.

The proportion of humanity forced to flee their homes and seek safety elsewhere has been rising, hitting new records every year for the last nine years. In 2020, the global number of forcibly displaced people reached 82.4 million – 1 in 95 people on earth – according to UNHCR. Today, 1.1 million among them come from Myanmar with nearly 900,000 “Forcibly Displaced Myanmar Nationals”, or FDMN, living in vast camps in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh.

Have you read?

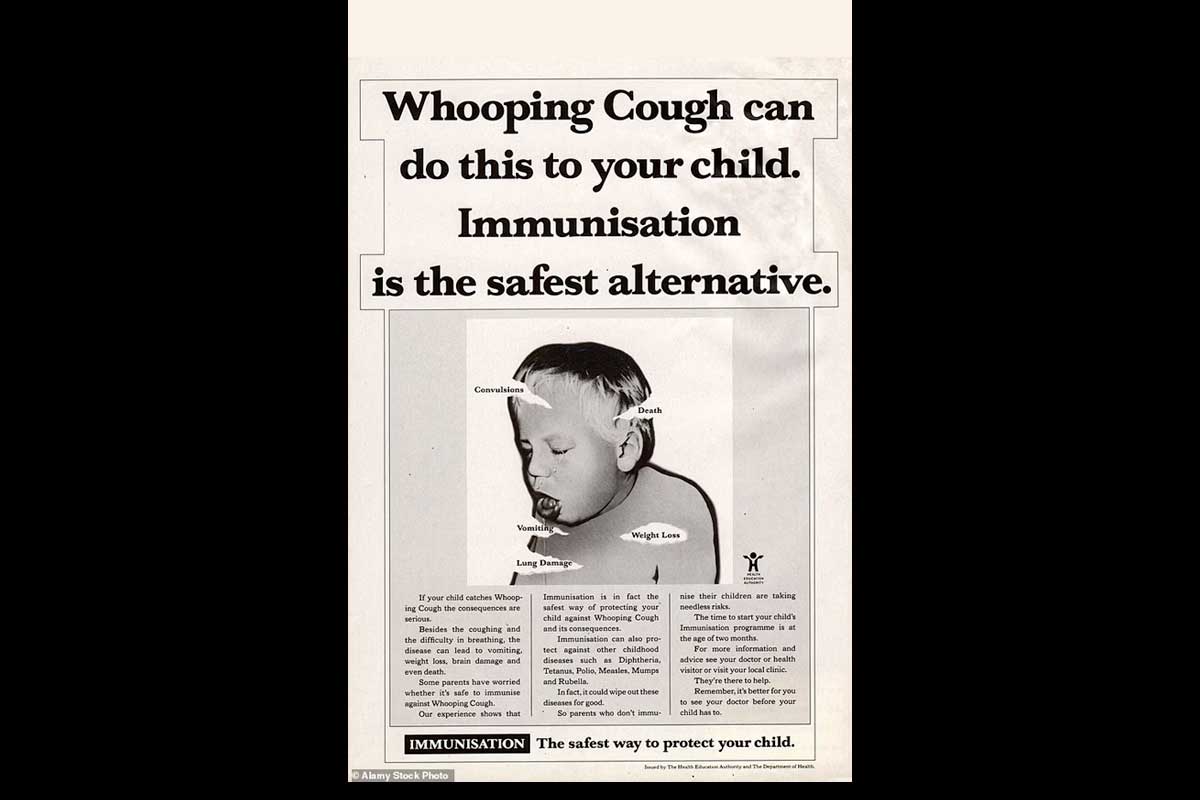

Even without a global pandemic, the camps – crowded, with limited sanitation, and subject to high temperatures and heavy rainfall – exist on the precarious brink of a public health crisis. “Every single day, I saw someone dying, or someone being buried,” the Magnum photographer Moises Saman said of his time at Cox’s Bazar in October 2017, as the camps scrambled to expand for the influx. Within a month, Cox’s Bazar was in the grips of an epidemic of diphtheria, the first outbreak in years of the deadly but vaccine-preventable disease. “This is an extremely vulnerable population with low vaccination coverage, living in conditions that could be a breeding ground for infectious diseases like cholera, measles, rubella and diphtheria,” said Dr Navaratnasamy Paranietharan, the World Health Organization (WHO) Representative to Bangladesh at the time.

(UNICEF/UN0143063/LeMoyne)

Abdullah, who found work assisting and translating for an epidemiologist in the colossal Kutupalong camp network, understands the outbreak as the near-inevitable product of a kind of generalised and unrelenting insufficiency: “my observation is it comes mostly from water, because of the unpurified water in the camp people were using,” he said. “Then, so many unclean foods – there was no gas stock to cook the food.... Then we didn’t get enough food to cook.” (Although unclean water and poor nutrition certainly compromise immunity, diphtheria usually spreads via respiratory droplets.) He had no idea whether he had been vaccinated as a child – there was a mark on his arm, but even his mother couldn’t remember which immunisation it recorded. As part of the emergency response to the outbreak, he received two doses of the diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis (DTP) vaccine, which appeared to keep him safe even as he worked with patients. But in December, his 75-year-old grandmother fell ill. He checked her throat with a flashlight and saw the distinctive greying of the pharynx, which he had learned to recognise as the definitive symptom. “I admitted her in the MSF clinic,” he says. “After eight days she became better. She came home.”

“Home” was by then no longer Auntie Yasmin’s. After two months, it was too cramped, and the newer arrivals moved on. In fact, the story of the four years Abdullah spent in Bangladesh is an unflaggingly restless one, an unceasing scramble for survival – for adequate housing, for work and money, and then, in 2020, for some sort of protection from the novel coronavirus. COVID-19 arrived as a double threat, the fear of disease shadowed by the dread of heavy-handed intervention by authorities.

Abdullah knew that social distancing was a tall order: “For me, in our shelter, we were eight members in my family – and then the problem is that there were three apartments [rooms] including the kitchen in my shelter. We had seven plates to use and one jug and two glasses. Everything is shared. There was no place to sit away from each other,” he said. When a neighbour became “seriously sick” they “urgently” sent him to quarantine – institutional segregation seemed the only way to limit the spread.

And yet, institutionalisation felt at moments like an even graver danger than infection. His grandmother, a smoker, had a cough. “When she coughed loudly, we were worried if we will be taken,” recalls Abdullah. He had heard a rumour of a sick woman in a different camp who was sent into quarantine, after which “the armies came, and they started catching people in that block.”

But it was a different kind of fear that brought Abdullah to the decision in late 2020 to leave Bangladesh – and his family – and return to Myanmar. It had been building gradually, the terrible feeling that his future was not only on hold, but at risk of being irretrievably compromised in Bangladesh. He had always planned to return to graduate school: to become a doctor, or if not a doctor then an engineer. He had won admission to a degree programme at a university in Chittagong, but without Bangladeshi paperwork, was not allowed to take up his place. Meantime, around him, he saw signs of a sort of social fracturing: “The refugee children, if they play, they use wrong words,” he said – disrespectful language he had never heard among the kids back home. Anxious not to judge, but alarmed nonetheless, he noted: “so many people don’t get jobs, and if they don’t have money to run their families, they start crime.” There was “lots of conflict situation” – between Rohingyas and Bangladeshis, Rohingyas and Rohingyas. “I realised that within three years, if people can become like that, in future what can happen?”

(UNICEF/UN0120414/Brown)

As 2020 neared its end, Abdullah learned that his father had died. His father had lived in Malaysia since Abdullah was a baby, had been a voice down a telephone line to him for almost all his life, but Abdullah had hoped to join him one day. His death was a twofold loss: of a loved one, and of an avenue to a brighter future. Abdullah called a family meeting, and announced his plan to leave. “I realised, actually, if I will stay in a refugee camp I will never be able to become a good wisdom,” he explained. Wisdom was a quality he invoked often when we spoke – an ideal that married career ambition and a higher kind of personal, even spiritual, growth.

The journey back was not much easier than the departure had been. He and a friend, together with three others, set out swimming across the Naf River one midnight in late December. At the halfway point of the crossing, a current ripped them off course. Twenty-five minutes later, they emerged, dripping, exhausted, only to find they were back where they had begun, on the Bangladeshi side of the river. In wet clothes, they shivered through until morning. That evening they tried the swim again, losing their bags in the current but battling through onto Myanmar soil. Four days later, they walked into Maungdaw township.

The plan was to get to Yangon, the former capital, to find a place at university. Abdullah paid a hefty fee for protected passage and set out for Sittwe, meaning to fly onwards to Yangon. “When we arrived in Sittwe, unfortunately we had one bad news, that our president is arrested, Aung Sang Suu Kyi. The airport was closed for one month.” Abdullah and his friend returned to Maungdaw, where they have remained since the February coup that brought the country under military control.

Abdullah lives in a new kind of limbo now – he has filed an application for formal repatriation, but hasn’t yet received his paperwork. On the road to his home village on Eid in May, he says he was stopped and questioned at five police checkpoints, no doubt a troubling reminder of his apparently unremitting precarity. And yet, even though seeing his burnt-out, overgrown village was “very different” from the homecoming he had pictured, it felt good: “I only feel satisfaction on my home floor,” he explained. “Wherever I go, my heart is always stuck in my homeland.”