Needle-free vaccines could be available within five years, but investment is needed

Researchers have called for pilot manufacturing facilities to be constructed ‘at-risk’, to ensure this game-changing technology is ready for deployment before the next pandemic.

- 17 May 2023

- 5 min read

- by Linda Geddes

Needle-free vaccines could transform immunisation, but investment is needed to hasten their development and help protect against future pandemics. Without it, development is likely to languish, with the first licensed patches not available for another decade, researchers say.

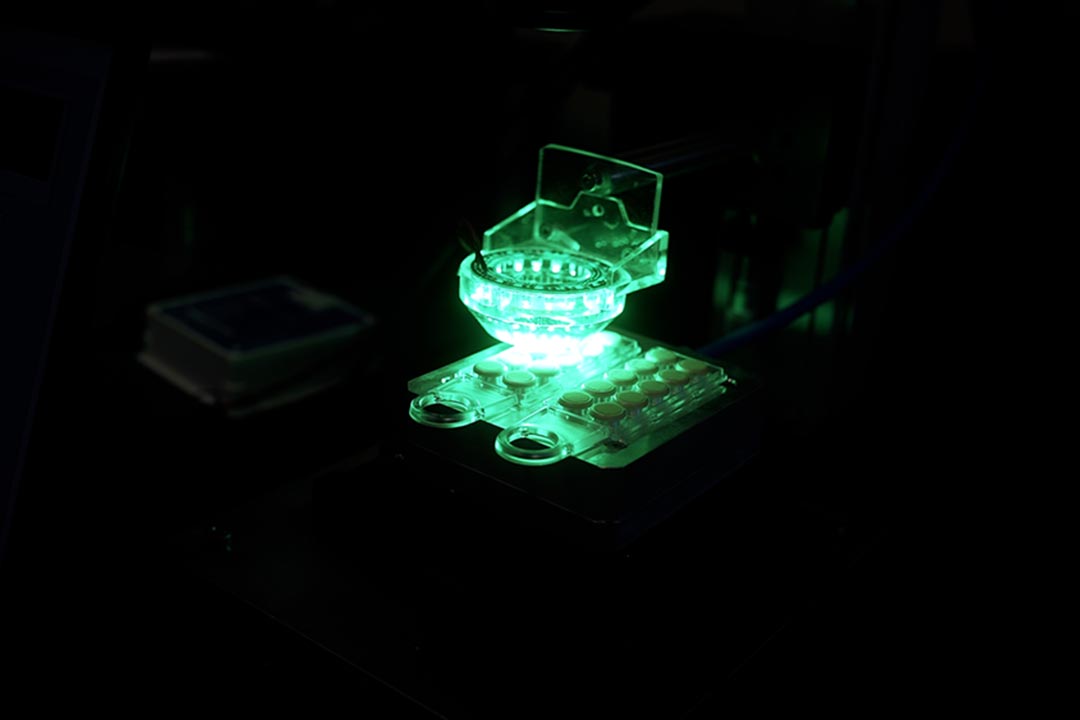

Vaccine microarray patches (vaccine-MAPs), also known as microneedle patches, consist of microscopic projections that are applied to the body like a small bandage, painlessly penetrating the skin's outermost layer to deliver a vaccine to the top layers of the skin.

Although microarray patches have been in development for several decades, none have yet been approved by regulators – although the COVID-19 pandemic has reinvigorated interest and investment in the technology.

They have the potential to overcome many of the logistical obstacles hindering vaccine deployment, ensuring these lifesaving interventions reach everyone, everywhere, as quickly as possible. Vaccine-MAPs could also ensure rapid deployment of protective vaccines in the event of future epidemics or pandemics.

Game-changing technology

As seen during the COVID-19 pandemic, bottlenecks can occur at various stages of the vaccine supply chain, from shortages of vaccine ingredients, packaging materials, and fill and finish facilities, to there being insufficient healthcare workers to deliver vaccines into people's arms.

Vaccine-MAPs could ease pressure on many of these bottlenecks. Because they're manufactured differently to traditional needle and syringe vaccines, there would be less competition for materials. They are also lighter than traditional vaccines, expected to be more stable at non-refrigerated temperatures, and easier to administer, simplifying their transportation and distribution – they could even be posted directly to clinics or people's houses. Those who dislike needles may also be more willing to be vaccinated using a patch.

Recent modelling by US healthcare consultancy firm Avalere Health estimated that, in a pandemic scenario similar to COVID-19, even if only 10% vaccines were delivered via microarray patches, the burden of disease could be reduced by 35% percent and deaths by 30% in the US, while the global economic impact could be reduced by US$ 500 billion over two years.

Roadblocks to success

Although microarray patches have been in development for several decades, none have yet been approved by regulators – although the COVID-19 pandemic has reinvigorated interest and investment in the technology.

Have you read?

Currently, one measles and rubella vaccine patch has completed a Phase 1/2 clinical trials with results expected to be published soon and two additional phase 1/2 clinical trials planned. Several COVID-19 and flu vaccine candidates are entering Phase 1/2 trials. Many others are undergoing preclinical assessment for various diseases including human papilloma virus (HPV) and rabies.

Even so, there are a number of hurdles to overcome before the potential benefits of this technology can be realised.

Because the vaccine in microarray patches is in a dry formulation, developers and manufacturers must ensure that enough antigen (the vaccine component that triggers an immune response) can be concentrated to deliver a full dose.

Standardised quality control tests and sterility requirements for vaccine manufacture must also be drawn up, and developers will also need to demonstrate that microarray patches would be acceptable to healthcare workers and the general public.

Dedicated facilities

However, arguably the most significant bottleneck is the lack of established production facilities for producing vMAPs at commercial scale – hence the call for investments to fund pilot-scale manufacturing facilities, with no absolute guarantee that it will be successful as is always the case with transformative innovations.

Sharing the cost of this investment between developers and manufacturers, global health organisations, and other donors, could significantly reduce the risk to individual organisations, while accelerating the availability of this technology, argues Dr Tiziana Scarnà, a senior manager in market shaping at Gavi.

Writing in the journal Expert Opinion on Drug Delivery, Scarnà and colleagues from WHO, UNICEF, The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, PATH, CEPI and the US Department of Defense and Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority, said: "The development of vaccines in response to the COVID-19 pandemic has shown that the traditional vaccine development timelines can be dramatically shortened with political commitment, at-risk funding, and intensive collaboration between all actors.

"Similar strategies could result in increased capital for at-risk investment in vaccine-MAP pilot production facilities and for supporting partnerships between microarray patch developers, vaccine manufacturers, and contract development and manufacturing organisations.

"It is possible that, with investments made now, one or two pilot facilities could be established in two to three years and the first licensure studies could be initiated in three years. This would likely incentivise additional investments in research and development, resulting in a global research and development portfolio with multiple vaccine-MAPs in development for both epidemic and endemic vaccines."

Flexible facilities

To further mitigate risks, the technology and manufacturing facility should be flexible enough that it could be applied to different vaccine targets and MAP platforms, depending on current needs. "It is also important that a facility is used in between epidemics – for example, for routine vaccines – both to justify the investment and to keep the facility ready for rapid response," Scarnà and colleagues said.

Taking these steps could at the very least ensure that vaccine patches will have undergone a minimum set of clinical trials before the next epidemic or pandemic hits. This means emergency use listing of the first vMAP could be available in less than five years.