HPV poses ongoing threat for older women, study finds

Routine screening often stops at 65 if previous smear tests have been clear, but new data suggests women remain at risk – indicating a need to rethink guidelines.

- 4 July 2025

- 3 min read

- by Priya Joi

Women over 65 years are still at risk of cervical cancer, and in some cases, might be at even higher risk than younger women, a study of more than 2 million women in China suggests.

The researchers say their finding that older women still have a significant risk of cervical cancer caused by human papillomavirus (HPV) infection warrants a rethink of current guidelines that say women don’t need to be screened after 65 years if they have a history of normal smear test results. This is especially important as the global population ages and more women live well beyond their 60s, they add.

Rethinking guidelines

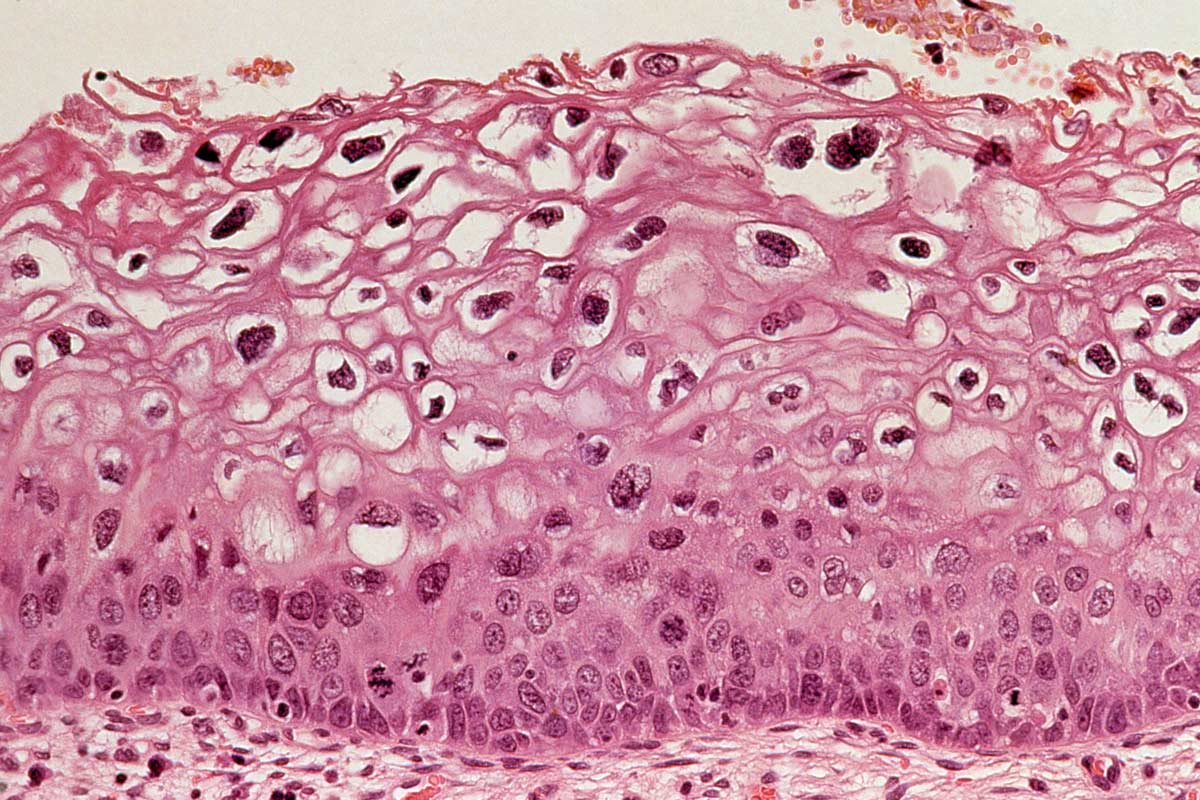

HPV is a common sexually transmitted infection, and while most cases clear on their own, persistent infections with high-risk forms of HPV can lead to the development of cervical cancer.

This disease claimed the lives of around 350,000 women in 2023, of which more than 90% were in low- and middle-income countries.

According to WHO statistics, in 2022 there were 157,182 new cases of cervical cancer in women over 65 years worldwide, and 124,269 deaths.

The new research found that the prevalence of high-risk HPV infections and cervical cell abnormalities is actually higher among women aged 65 and older compared to younger women.

Elevated risk

Zichen Ye at the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College in Beijing, China, and colleagues retrospectively analysed cervical cancer screening data and HPV vaccination status for 2,152,766 women from across Shenzhen, China, collected between 2017 and 2023.

Just over 2% of the women had been vaccinated against HPV, as the vaccine only became available to women in China in 2017. Of the total group, 1% or 17,420 of women were aged 65 and above – cervical cancer screening is not routine for women in this age group.

The study, published in BMJ Global Oncology, reported that nearly 14% of women aged 65 and above had high-grade cervical cell abnormalities (CIN2+), while the rate among younger women was less than 9%. CIN2+-grade abnormalities are classed as moderately abnormal cells in the cervical lining. Although such cases may clear up on their own, women with CIN2+ are generally monitored or treated as these cells can progress to cervical cancer if left untreated.

Women over 65 years were also more likely (23% vs. 16.5%) to be infected with several different types of HPV and more likely to have abnormalities picked up on screening (just over 7% vs. just over 4%).

These results suggest that a significant portion of older women remain at risk for cervical cancer, particularly if infections are not detected and treated.

Have you read?

Ageing population

The findings have important implications for public health policy and cervical cancer prevention. As life expectancy rises worldwide, more women are living well beyond their 60s, and many may not have had access to regular screening earlier in life.

The study’s authors argue that continuing cervical cancer screening is the best way to detect and prevent cases as cell abnormalities are often asymptomatic. Stopping screening at a fixed age could leave many women vulnerable, especially in settings where screening coverage has historically been low.

Persistent high-risk HPV infections are the main cause of cervical cancer, and the results from this large study, combined with WHO data on cervical cancer deaths in older women, suggests that the risk does not disappear at age 65. The researchers suggest that decisions about when to end screening should consider individual risk factors and screening history, rather than relying solely on age.

This research highlights the need for ongoing vigilance. As cervical cancer remains preventable through vaccination and screening, adapting policies to reflect new evidence could help save lives and reduce the burden of disease among ageing populations.