‘No progress’ in tackling premature births – UN

UN report says urgent investment in antenatal care is needed to reduce premature birth rates.

- 10 May 2023

- 5 min read

- by SciDev.Net

No measurable progress has been made in any region of the world in the last decade to reduce the number of babies born prematurely and thus vulnerable to loss of life, a major UN report reveals.

Preterm birth, where babies are born in the first 37 weeks of pregnancy, is now the single largest cause of child mortality, accounting for more than one in five deaths of children under the age of five, according to new analysis in the Born Too Soon report.

In 2020 an estimated 13.4 million babies were born early, nearly one million of whom died due to complications of preterm birth.

“Ensuring quality care for these tiniest, most vulnerable babies and their families is absolutely imperative for improving child health and survival.”

Anshu Banerjee, WHO director for maternal, newborn, child and adolescent health and ageing

The report, by the WHO, UNICEF, and the Partnership for Maternal, Newborn and Child Health, says failure to invest in health care for pregnant women and newborns is partially to blame for the stagnation in progress, while conflict, climate change, and COVID-19 have added to the risks.

Research published this week in The Lancet says implementation of a handful of low-cost interventions could prevent more than one million newborn deaths and stillbirths in developing countries.

“Ensuring quality care for these tiniest, most vulnerable babies and their families is absolutely imperative for improving child health and survival,” said Anshu Banerjee, director for maternal, newborn, child and adolescent health and ageing at the WHO.

He said progress was also needed to help prevent preterm births from occurring in the first place, adding: “This means every woman must be able to access quality health services before and during pregnancy to identify and manage risks.”

Unequal burden

The report, including analysis from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine in the UK, reveals immense survival gaps between rich and poor settings. Roughly nine in ten babies born before 28 weeks survive in high-income countries compared with less than one in ten in low-income countries.

Have you read?

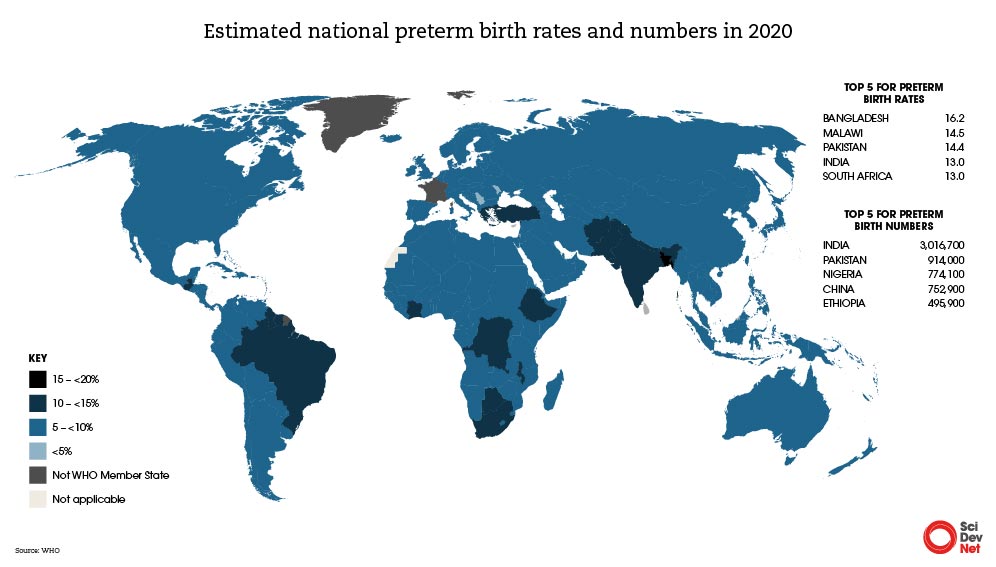

South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa have the highest rates of preterm birth, with premature babies in these regions facing the greatest mortality risk. The two regions together account for more than 65 per cent of global preterm births.

In 2020, almost half (45 per cent) of all preterm babies were born in just five countries: China, Ethiopia, India, Nigeria and Pakistan.

Developed by more than 140 individuals from 46 countries, spanning national governments and civil society actors such as patients’ groups, the report states that over the past decade there has been “no change” in reducing preterm birth rates in any region.

And in almost all countries with reliable data, preterm birth rates are increasing.

Births data lacking

However, paucity of data remains a major obstacle to tackling the problem. Extensive data on preterm births is available only from high-income countries, where monitoring systems are generally more robust and antenatal ultrasound is more often used.

Most countries do not report national civil registration and vital statistics on preterm births, meaning the true scale of the problem is hidden.

The report, which comes a decade on from the last major UN report on the issue, calls for the standardisation of definitions, measurement and reporting of preterm birth rates.

In the decade between the two reports, opportunities were missed due to such lack of data, says Neena Khadka, senior newborn health advisor at the charity Save the Children US.

“While the [first] Born Too Soon report tried to bring attention to the smaller newborns, there was so much that needed to be done for every newborn,” Khadka tells SciDev.Net.

“Anyone who has a newborn needs attention, because that’s the basic requirement, and they were not getting it.”

Twenty years ago most births globally took place at home, but “we didn’t even have data to tell us what was happening to the newborn,” she says. “So we spent two decades focusing on newborns that are born at home.”

Today, more than 80 per cent of births occur in facilities, according to the Lancet research.

The authors of the analysis estimate that 476,000 newborn deaths and 566,000 stillbirths could be avoided each year if eight preventative interventions were fully implemented in 81 low- and middle-income countries. These include simple measures such as access to vitamins, antimalarials, protein supplements and aspirin.

Birth prevention

The UN report, presented at the International Maternal Newborn Health Conference (IMNHC) in Cape Town, South Africa this week (8-11 May), calls for increased investment and acceleration of policies to improve maternal and newborn health and bridge inequalities.

The WHO recommends antenatal ultrasound (before 24 weeks) for all pregnant women — a recommendation that is a challenge for many low- and middle-income countries because of lack of resources.

In 2022 the WHO released a set of recommendations to help improve the health of preterm infants.

The recommendations focused on two specific interventions: the use of antenatal corticosteroids to help prevent respiratory-related morbidity, and tocolytic treatments that inhibit contractions of the uterus to delay labour.

Delaying labour creates time for women to be transferred to a higher level of care, if necessary and possible.

Last year the WHO also updated its guidelines on “Kangaroo mother care” (KMC) – where a mother has skin-to-skin contact with the newborn to breastfeed – for premature babies. For infants born before 37 weeks of pregnancy, it recommends KMC by mothers, fathers or care-givers immediately after birth without an initial period in an incubator.

“Improving outcomes is not always about providing the most hi-tech solutions,” said WHO director-general Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus at the launch of the KMC guidelines.

Reflecting on what is needed to make the next decade more successful, Khadka echoes this sentiment. She stresses the need for “back to the basics, no zero separation… caring for the mum and the baby together”.

This article was produced by SciDev.Net’s Global edition.

Written by

Website

This article was originally published on SciDev.Net. Read the original article.