Nose sprays, needle-free patches, durable immunity: towards the next generation of COVID vaccines

The development of COVID vaccines has already been explosive. There are more innovations on the way.

- 9 November 2021

- 6 min read

- by The Conversation

The past 20 months has seen an explosion of vaccine development, with COVID vaccine testing and rollout happening at an unprecedented pace in the face of a global pandemic. There have been absolute triumphs – the fact we have multiple safe, effective vaccines is remarkable – but there have also been challenges.

We’ve seen storage and delivery issues, vaccine hesitancy, breakthrough infections and the beginnings of waning immunity.

Vaccine innovators around the world have these challenges in their sights. They are already working on the next generation of COVID vaccines.

Tweaking current vaccines

After hundreds of millions of doses, we have a good handle on how current vaccines are performing and where they can be improved. As more data is gathered, a modified dose, time between doses, and/or using different vaccines together in mix-and-match strategies may become the preferred approach.

We could also improve vaccines that aren’t performing at their best.

Inactivated vaccines have been used in many parts of the world but their early protection has waned, particularly in older people, with the World Health Organisation now recommending a third dose.

One way to improve this could be to add an adjuvant – something that fires up the immune system. One such vaccine, called Valneva, has early results that suggest including an adjuvant improves immunity.

Making vaccination easier

As we have seen, vaccinating large numbers of people is not easy. Innovations to make this easier will be welcome.

Needle-free approaches would be ideal. One approach, known as a nanopatch vaccine, coats the vaccine onto tiny spikes on a small patch.

The patch is applied to the skin and the spikes deliver the vaccine to a dense barrier of immune cells sitting just under the top layers of our skin. A nanopatch COVID vaccine developed by Vaxxas and researchers in Queensland has been shown to trigger strong immune responses in animal models, with trials underway in humans.

Have you read?

Another approach, known as an intranasal vaccine, sprays a vaccine up the nose. This would be easier to deliver and it could also build immunity in the right location in our body.

The coronavirus infects us through the lining of the nose, mouth, throat and lungs – a type of sticky tissue that lines body cavities and some organs called mucosa.

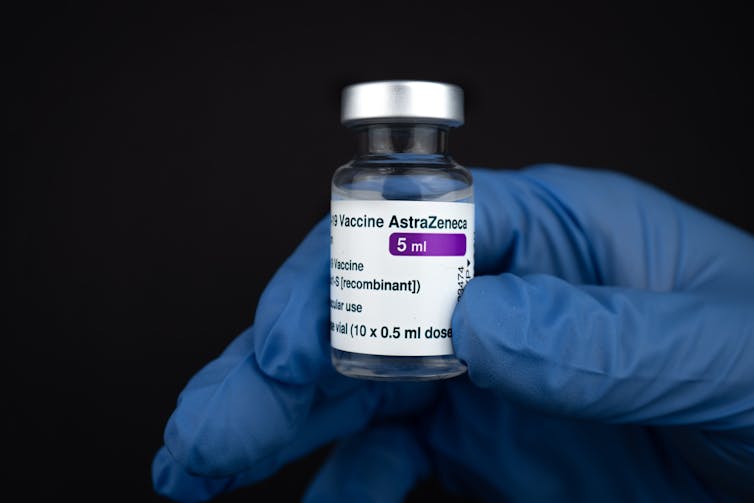

Currently, COVID vaccines are delivered into our arm muscle and build antibody levels in our blood and tissue, with some antibody spilling out into the mucosa. Delivering the vaccine directly to the mucosa might be a better approach for preventing COVID infection. This is being trialled with a number of vaccines, including the AstraZeneca vaccine.

#LifeSciences 📢 news of the week:

— APPG for Life Sciences (@LifeScienceAPPG) November 5, 2021

👃#Covid-19 vaccine nasal spray is trialled

🥼New #diabetes test enables some patients to stop taking insulin

📑@beisgovuk conducts major review of @UKRI

If yearly COVID boosters are recommended for some or even all of the population, it would be easier to deliver them together with the yearly flu vaccine. These “multipathogen” vaccines are being tested with current flu vaccine or even new types of flu vaccine.

More durable immunity

With two doses of the current vaccines, immunity is seen to decline and poor responses are seen in certain groups such as the severely immune-compromised and older people. COVID vaccines that can induce more durable immunity, more consistently across vulnerable populations would be a major innovation.

This could require completely new vaccines. Protein subunit vaccines – which use purified protein from the surface of the virus as a target – are still working their way through approvals around the world.

One example is the Novavax vaccine, but there are a large number of other protein subunit vaccines also development that often use new adjuvants – again, the vaccine ingredient that fires up your immune system. These new adjuvants could support more durable immunity but this remains to be tested.

Protection against future variants

We can also update the current vaccines by changing their target. All current COVID vaccines use a target from the original strain of the coronavirus to train the immune system.

This is okay for vaccinating against the Delta strain, as this new virus still looks pretty similar to the original virus to your immune system. But new viruses could emerge that the immune system struggles to recognise.

We could simply use a new target from a new virus. Some vaccines have been updated to target the Beta strain, which is relatively hard for our immune system to recognise. Trials are being run with these Beta-targeted vaccines as a dry run, to make sure that we can update vaccines if we need to.

A more ambitious approach would be to focus the immune response on a target/s common to all coronaviruses. This “pan-coronavirus” vaccine would hopefully provide protection from all or most coronaviruses. Again, early data from animal models are promising.

TOP ARTICLE: Our most popular article this week was @cbaker_research + Andrew Robinson from @UniMelb's explainer on how unvaccinated people are 10x more likely to contract COVID + more likely to pass it.https://t.co/gZHRbaCkFU

— The Conversation (@ConversationEDU) October 31, 2021

Working out if vaccines are working

An important innovation for COVID vaccines would be an immune correlate.

An immune correlate is something that can be measured in an immune response to indicate if someone will be protected against infection or not. For rubella and hepatitis B virus, we measure the amount of antibody targeting these viruses in our blood. If antibody is absent or too low, a booster dose of the vaccine is recommended.

An immune correlate for COVID could similarly allow us to identify people that need a booster.

Some researchers, including Australian teams, are sorting through data from around the world to see if there is something we can measure in our immune response to use as a correlate for COVID.

Research around the world is driving us towards the next generation of COVID vaccines. Innovations for COVID vaccines will lead to better vaccines for other infections too – those that currently afflict humanity and those that are yet to emerge.![]()

Authors

Kylie Quinn, Vice-Chancellor's Research Fellow, School of Health and Biomedical Sciences, RMIT University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Disclosure statement

Kylie Quinn receives funding from the Rebecca L. Cooper Foundation, CASS Foundation and the Medical Research Future Fund.

Partners

RMIT University provides funding as a strategic partner of The Conversation AU.