What is the blood clotting disorder the AstraZeneca vaccine has been linked to?

The European Medicines Agency has concluded that there is a possible link between AstraZeneca’s COVID-19 vaccine and very rare blood clots. But what are these clots and how great is the risk?

- 8 April 2021

- 8 min read

- by Linda Geddes

After its initial finding last month that there was no convincing link between the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine and rare blood clots, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) has now concluded its investigation and announced that unusual clots with low blood platelets (small fragments that enable blood to clot) should now be listed as a possible “very rare side effect” of the vaccine. However, having reviewed data from 190 million AstraZeneca vaccinations, compared to the 34 million considered by EMA, the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Global Advisory Committee for Vaccine Safety (GACVS) issued an interim advisory that a causal relationship, while plausible, had not been confirmed. Both organisations stressed that the benefits of the vaccine in terms of preventing deaths and serious disease from COVID-19 still outweigh its risks.

Even though your chances of developing a blood clot or low platelets after receiving the AstraZeneca vaccine is very low, you should be aware of the symptoms so that you can get prompt medical treatment, if necessary.

These announcements also show that the adverse events monitoring systems, which are designed to identify any rare side effects that weren’t detected during clinical trials, are working. Even once they’re licensed, the safety of all COVID-19 vaccines continue to be monitored, with any relevant side effects investigated in detail and action taken where necessary

What sort of clots?

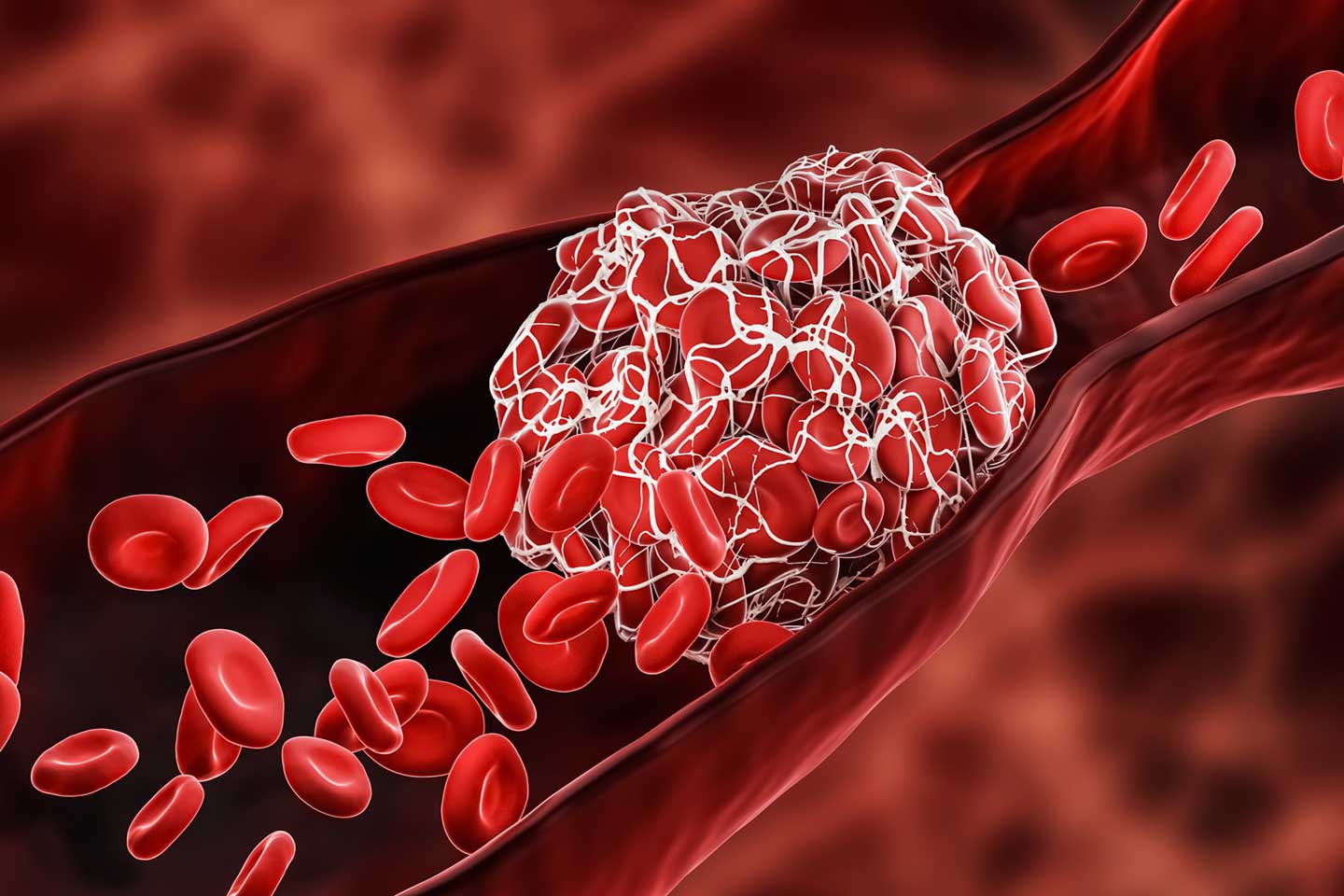

The blood clots causing the greatest alarm are called cerebral venous sinus thromboses (CVST), which occur in the veins draining blood from the brain. These can be fatal. Blood clots also occurred in the abdomen (splanchnic vein thrombosis, or SVT) and in arteries. In most of the patients identified so far, these clots occurred in combination with thrombocytopenia, a condition characterised by abnormally low numbers of platelets and sometimes bleeding.

Having a low platelet count puts you at an increased risk of heavy bleeding, because it makes it harder for blood to clot. Although it may therefore sound odd that clots and low platelets can occur at the same time, this does happen in other rare conditions. An example of this is heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT), an immune-related complication that sometimes occurs when people are given the blood-thinning drug heparin. Here, patients produce antibodies against a platelet protein called P4 when it is bound to heparin, triggering blood clots and consuming platelets. Some scientists have proposed that something similar might be happening in a small number of people who receive the AstraZeneca vaccine. This has not been proven, although the EMA’s safety committee agrees it could be a plausible explanation, and has requested new studies and amendments to ongoing ones to provide further insights and information.

Importantly, HIT and related conditions are treatable with other non-heparin drugs, as well as antibodies that destroy the problematic antibodies. So, by recognising the signs of bloods clots and low blood platelets and by treating them early, healthcare professionals can help those affected to recover. For the same reason, anyone with clot-related symptoms (see below) should immediately seek medical advice.

How many clots?

The EMA’s safety committee carried out an in-depth review of 62 cases of CVST and 24 cases of SVT reported in the EU drug safety database (EudraVigilance) as of 22 March 2021. Eighteen patients died. The cases were mostly identified through spontaneous reporting systems within the European Economic Area and the UK, where around 25 million people have received the vaccine.

However, WHO’s GACVS stated that more information from regions outside of Europe and the UK was needed to fully understand any potential relationship between vaccination and possible risk factors. Based on its analysis of more than 190 million doses of the vaccine being administered, 182 cases of thromboembolic events with thrombocytopenia had been reported. “If there is a causal link, the events are very rare and the risk is extremely low,” it said.

According to the EMA’s findings most of the clots reported occurred in women under the age of 60 within two weeks of vaccination. No increased risk was observed among older individuals who received the vaccine. Because of this, some countries have decided to restrict use of the vaccine in younger individuals.

Have you read?

Weighing the risks

All medicines, even paracetamol or ibuprofen, carry a risk of rare but serious side effects but we still use them. The EMA’s safety committee has stressed that the reported combination of blood clots and low blood platelets is very rare, and the overall benefits of the vaccine in preventing COVID-19 still outweigh the risks of side effects.

Of course, this risk-benefit ratio is likely to be higher in some groups of individuals than others. We know that older individuals, and those with other underlying illnesses such as high blood pressure, cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes and obesity are at greater risk of serious COVID-19 disease or death than younger individuals. However, young and healthy people can, and do, catch the virus, and some of them become seriously ill. Then there’s the risk of “Long Covid”, which appears to be higher among middle-aged individuals, particularly women.

The EMA says it has not yet identified any specific risk factors, such as age, gender or a previous medical history of clotting disorders, for these very rare events. Although most cases appear to be in women, it is hard to disentangle the association with sex-related differences in the immune response, or the role of hormonal contraceptives or other hormone therapies which are also risk factors for clots.

Curiously, similar clots are not being reported for other COVID-19 vaccines, but this could be because, in many countries, they are being used in different population groups. It will take some time to disentangle all of these factors, but currently the benefits of the vaccine clearly outweigh the risk of rare events, especially for older age groups.

How risky?

The UK’s Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) has carried out its own review of 79 reported clotting events occurring in the UK up to 31 March. All occurred after a first dose of the vaccine. During the same time period, 20.2 million doses of the AstraZeneca vaccine had been administered, suggesting that the overall risk of blood clots is approximately four people in a million who receive the vaccine.

Of these clots, 44 were CVSTs and 35 were clots in other major veins – all occurring with low blood platelets. Sadly, 19 of those affected died – three of whom were under the age of 30.

As mentioned above, the risks associated with catching COVID-19 are lower for younger age groups, so how do they compare with the very small risk of developing a blood clot from the AstraZeneca vaccine?

The Winton Centre for Risk and Evidence Communication at the University of Cambridge has calculated this for various scenarios and age groups, based on the numbers of blood clots detected in different age groups within the UK. This means the estimate of serious harm due to the vaccine is slightly different to the “four in a million” figure given above. However, we should be cautious about these estimates because of the low numbers of people in each band, and possible differences in the numbers who have received the vaccine in each age band.

Assuming a low rate of coronavirus cases in the community (equivalent to 20 per 100,000 people), the risk of being admitted to an intensive care unit (ICU) with COVID-19 for someone aged 20-29 is 8 per million people, versus 11 per million for the risk of serious harm from the vaccine in this age band. However, if a country has high rates of infection (equivalent to 200 cases per 100,000 people), the risk of ICU admission for someone aged 20-29 is 69 per million people – higher than the risk associated with receiving the vaccine.

For someone aged 60-69, the risk of ICU admission in this scenario is 1,277 per million people, versus a risk of 2 per million for the risk of serious harm from the vaccine.

For this reason, even though the MHRA is not recommending age restrictions, the UK government has decided to offer people in their twenties an alternative COVID-19 vaccine, which has not been linked to these extremely rare blood clots.

It is important to remember, however, that as more data becomes available for larger population sets these risk scenarios may change, not just as more people are vaccinated but also as the number of people killed by COVID-19, currently at 2.87 million, continues to rise. GACVS is due to reconvene on 13 April, after which it will issue its conclusions and recommendations.

What to do if you’re concerned

Even though your chances of developing a blood clot or low platelets after receiving the AstraZeneca vaccine is very low, you should be aware of the symptoms so that you can get prompt medical treatment if necessary. These include: breathlessness; pain in the chest or stomach; swelling or coldness in a leg; severe or persistent headaches or blurred vision; or tiny blood spots under the skin beyond the site of the injection. You should seek urgent medical attention if you have any of these symptoms in the weeks after your injection.

Serious side effects from vaccines are rare but they do occur, with any vaccine and for any disease. However, regulators stress that it is important to remember that we are witnessing the largest mass vaccination campaign in history. Given the high number of people being vaccinated and the attention focused on the vaccines and the pandemic, some rare reactions are to be expected. It remains to be seen if similar concerns will be raised over other COVID-19 vaccines, but given that AstraZeneca’s was the first to be approved and has been given to far more people than any others, any rare adverse events are more likely to show up simply because of the sheer volume of people to have received it.