“A huge step forward”: malaria vaccines roll out in Mali

Mali is taking a historic step by introducing an anti-malaria vaccine through a novel approach. Driven by the commitment of health workers, local communities and religious leaders, the introduction raises hopes for a safer future for children.

- 2 May 2025

- 7 min read

- by Aliou Diallo

In Mali, every family, every village, every neighbourhood lives under the heavy shadow of malaria.

Despite the mass distribution of insecticide-treated mosquito nets, awareness campaigns and preventive treatments for pregnant women, the disease continues to claim lives.

It remains the main reason for medical consultations, hospital admissions and deaths among children under five – a stubborn scourge.

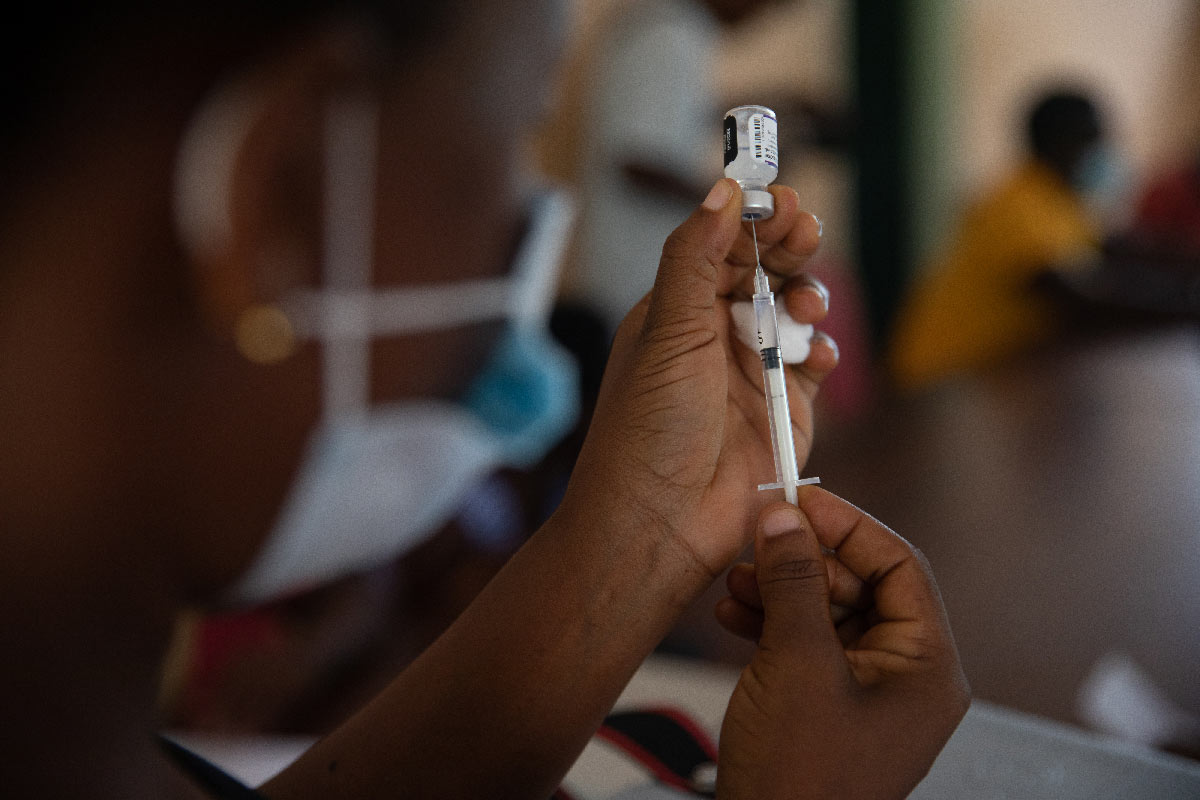

In this context, the announcement of the roll-out of the first-ever anti-malaria vaccine has sparked a wave of mobilisation across the country.

The official launch took place on 25 April, coinciding with World Malaria Day, in the commune of Kalaban-Coro on the outskirts of Bamako.

The R21/Matrix-M vaccine will first be deployed in 19 priority health districts across five regions – Kayes, Koulikoro, Mopti, Ségou and Sikasso – and will target children aged 5 to 36 months, following a five-dose vaccination schedule.

This vaccine will complement existing prevention tools rather than compete with them. According to WHO recommendations, the best individual protection for children under five combines vaccination, seasonal malaria chemoprevention (SMC) and the use of insecticide-treated mosquito nets.

A hybrid approach

Mali has also become the first country in the world to adopt a hybrid approach to malaria vaccination.

Under this innovative protocol, children will receive three initial doses spaced closely together, administered at specific times throughout the year. A fourth and fifth dose will then be given seasonally, each year just before the rainy season – a strategy designed to maximise protection during the peak transmission period.

This strategic innovation could become a model for other African countries facing seasonal malaria transmission.

According to WHO’s 2024 World Malaria Report, Mali accounted for 3.1% (or 8.15 million) of global malaria cases and 2.4% (14,328) of malaria-related deaths in 2023.

The country ranks among the 11 most affected worldwide and is one of eight countries that saw a marked increase in cases between 2019 and 2023, with 1.4 million more cases over that period. Globally, the African Region bears the overwhelming burden of the disease, with around 94% of cases and 95% of deaths.

In the face of this burden, the hope for a lasting decline in malaria is gaining ground – driven above all by the daily commitment of communities. Bereaved mothers, overstretched health workers, dedicated religious leaders: all are united in their determination to protect children and break free from this devastating disease.

Families scarred by malaria

In Ségou, 240 kilometres from Bamako, the vegetable market is buzzing with life. Dozens of women tend to their stalls, exchanging laughter, bargains, and daily news.

When word spreads that a malaria vaccine has arrived, a ripple of joy runs through the “Sugu Thini Sugu” market in Hamdallaye. Each woman has her own tale, her own scar tied to a disease that has long haunted their daily lives. Soon, they all point to a young woman in her thirties, whom they believe carries a particularly powerful story.

Aïssata Diallo, mother of three, sweat on her brow and a baby strapped to her back, steps forward to speak, her voice heavy with emotion:

“I lost my son Moussa when he was five. A sudden fever, then a coma – and in two days, he was gone. Malaria is like a thief that stalks the night. Since then, every time one of my children has a fever, I can’t sleep. If this vaccine can spare other mothers what I’ve been through, it will be a blessing.”

Beyond the human pain, malaria also places a heavy economic burden on families. In a small metalworking shop in Ségou, hammers ring against steel sheets under the blazing sun. Dressed in dusty work clothes, the labourers hammer, weld and polish non-stop, making doors and windows.

It is in this setting that Mamadou Traoré, a metalworker for the past ten years, speaks of the hardships malaria imposes:

“Every time one of my children falls ill, I have to find money for the consultation, the medicine – sometimes even just to pay for transport to the health centre. My salary barely covers food for the family, so when malaria hits, I sometimes have to go into debt. Malaria doesn’t just kill – it impoverishes.”

Beside him, his workshop supervisor, Boubacar Keïta, adds:

“Here, in our neighbourhood, it’s malaria that hits us the hardest. If a vaccine can protect our children and our families, that alone would be a huge step forward.”

Have you read?

A new and long-awaited ally

In community health centres, preparations are underway. With the rainy season approaching, health workers are on high alert, knowing that another wave of malaria-stricken children is inevitable.

In Sirakoro, a working-class neighbourhood of Bamako, Dr Oumar Konaté, head doctor at a private clinic, describes a situation now sadly familiar across the country’s health centres:

“During the rainy season, we see so many children with malaria that we lose count. Sometimes there aren’t enough beds, and families end up sleeping on the floor next to the patients. We do our best, but without long-term prevention, it’s a losing battle.”

For medical staff on the frontline, the arrival of the vaccine is a welcome development.

“This vaccine could change everything. It finally gives us the chance not just to treat malaria, but to prevent it. It’s a tool we’ve been waiting for,” adds Dr Konaté.

In remote villages, health workers are often the first line of defence during epidemics. Aminata Sidibé, a mobile vaccination agent, shares her experience:

“When I visit villages to administer the usual vaccines – against measles, polio, or tuberculosis – I see so many children laid low by malaria. It breaks my heart. Something’s missing. That something is this vaccine.”

Aminata recalls having taken part in past campaigns to distribute SMC (seasonal malaria chemoprevention) tablets, aimed at boosting children’s resistance during the rainy season.

The combination of SMC, vaccination, and insecticide-treated nets now offers the highest level of protection for children under five.

Community leaders at the heart of mobilisation

In villages and neighbourhoods, community and religious leaders play a crucial role in building trust around any new vaccine. In Malian society, their voices carry weight. They serve as natural intermediaries between health authorities and the population. Imams, village chiefs, respected elders, or heads of community groups – all help shape and influence public opinion.

Their support is essential, especially to counter the fears and rumours that often surround vaccination campaigns. With news of the imminent arrival of the malaria vaccine, Imam Amadou Bamba, a well-respected figure in his community, has committed to personally raising awareness among his congregation.

“Many people here are still wary of vaccines. But the importance of vaccination is undeniable,” he says. “Thanks to vaccines, our children are now protected from many diseases that once devastated families. As an imam, I tell them that protecting yourself from illness is also honouring the life God has given us. If we all come together, this malaria vaccine can save our children.”

More from Aliou Diallo

Recommended for you