Uganda’s malaria vaccination programme is picking up pace

Families and health leaders say community health workers deserve much of the credit for rising uptake.

- 8 September 2025

- 6 min read

- by John Musenze

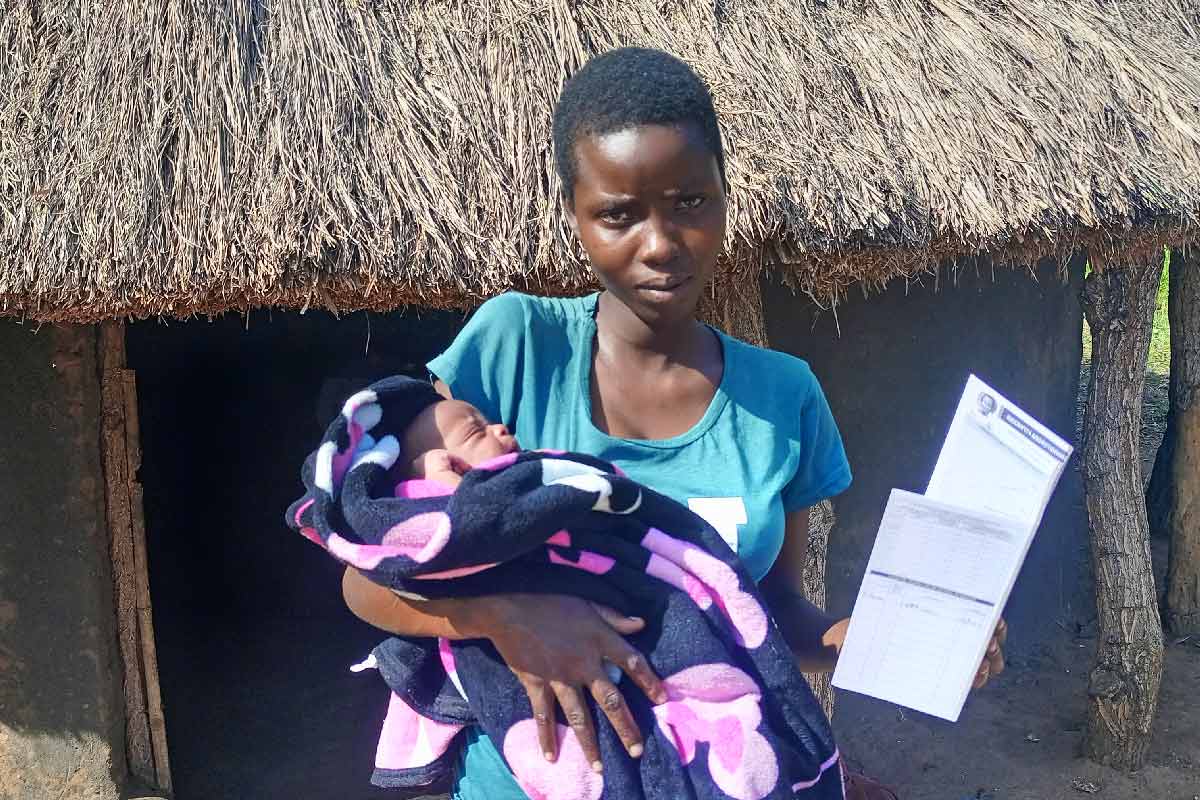

When Uganda kicked off its malaria vaccination programme in April, 29-year-old Hawa Umulu was hesistant to bring her baby daughter for the jab. People around her were talking, articulating shadowy concerns about the still-unfamiliar vaccine. Umulu was nervous.

That left her between a rock and a hard place. In Maracha district, where Umulu lives, malaria is common. At just one year of age, Umulu’s daughter had already survived one bout of the parasitic infection.

The brush with the deadly illness not only threatened the child’s life, it also affected Umulu’s finances. Each hospital visit had cost her more than 30,000 shillings (US$ 10), she said: a huge cost for a jobless mother. Her only other option, Umulu says, would have been using a government hospital that offers free services but was located two kilometres away, a distance that felt impractically far from home.

Widespread danger

Malaria remains the country’s leading cause of illness and death among children, with 16 million cases recorded in 2023 according to the World Health Organization (WHO). The disease accounts for 40% of all outpatient visits, 25% of all admissions and 14% of deaths in Uganda.

In Maracha district, West Nile, the crisis has been especially pronounced, according to Sunday Cadribo, District Health Educator, who says malaria has long dominated outpatient statistics.

“In 2020, 57% of all outpatients tested positive for malaria – that was 146,246 people. By 2021 it rose to 59%, and in 2022 it was 62%, that’s why this vaccine came in at the right time,” he told VaccinesWork.

Interventions such as indoor residual spraying and mosquito net distribution have helped. But the introduction of the malaria vaccine in 2025, with a roll-out of 2.278 million doses in 105 high- and moderate-transmission districts, marks a new chapter in malaria prevention.

Trusted voices

Umulu’s child would be less likely to experience further episodes of malaria, Community Health Extension Workers (CHEWs) explained, if she was immunised.

“For two months I was worried,” said Umulu, “but then the Community Health Extension Worker kept coming back. She explained everything clearly. Finally, I took my baby for the first dose in June, the second this August, and we are going for the third in September,” she recalls.

Umulu noted that ever since her child had received her first shot, she had not had any episodes of malaria. She also pointed out that her daughter had not experienced any side-effects from the vaccine, despite the rumours.

“Unlike the doctors in the hospitals, these community workers are always with us and we see them as part of us,” Umulu said. “They keep checking on my daughter even after the first jab and I feel safe to have taken that decision thanks to them.”

Though swirling misinformation has raised the spectre of dented uptake, Uganda has widely accepted the malaria vaccine. Maracha now reports uptake rates of between 85–90%, according to district data.

Building momentum

Parents and health administrators across the country credit CHEWs, like Maureen Yesco, with a leading role in driving those uptake rates.

Assigned to Alivu parish, Yesco walks between 5 and 20 kilometres a day, visiting households spread across hilly terrain, sitting down with parents in their homes and explaining to them that the vaccine has been proven safe, and is a vital guard for their children’s safety.

Yesco noted that the first month of vaccination was not an easy one. She recalls “negative attitudes” from the community, with many parents expressing hesitation to vaccinate their children.

“We initiated community outreach and started programmes from the worship places and markets, where we encourage mothers to bring children to the facility. [Children] are vaccinated under our watch, and we also liaise with the facility to take the vaccine to different vaccination points in the villages at least twice a week. We engage the parents, local, religious and opinion leaders during the outreach, and this has helped us a lot,” said Yesco.

“Vaccine misinformation was common before even the vaccine came in, but there was a [knowledge] gap about its efficacy amongst the people. When we move around, we even give examples of those whose children have been vaccinated and did not get any problem after, then we tell them that Uganda is not the first country to take this vaccine, and no one has ever died because of it – they were lied to,” Yesco said.

Peddling evidence-based information

In Maracha’s Ojiba village, meanwhile, CHEW Morris Osuga has been using mobile-moving media – large speakers – to spread evidence-based information about the vaccine.

Osoga, previously a village health team (VHT) member, said, “before we did door-to-door sensitisation, people were talking negative especially in some cells. We use simple and clear [messaging in the] local language that they understand. We emphasise the importance of vaccines in preventing serious diseases and protecting the community – and then I tell them that even my children have been vaccinated and I did it because I trust the vaccine,” Osoga said.

Riding a tricycle mounted with speakers, Osoga moves throughout the community, stopping at markets, churches and any other large gathering to pass information to the community. Many people here have neither smart phones nor televisions to watch educational content about the vaccine from the health ministry, he explained.

“We have not received any cases of side effects of the vaccine, which many used to enquire about before,” Osuga noted. “Now many people are welcoming us and the vaccine unlike before.”

Unlike traditional broadcasting – via TV or radio, for instance – Osuga’s tricycle-mounted broadcasting system creates opportunities for two-way conversation. He welcomes community questions as he makes his rounds, happy to be able to respond immediately.

Esther Asibazuyo, a 32-year-old mother of four children from Bura Opidri village, Alivu parish in Kijomoro Subcounty, says she has benefitted from Osuga’s efforts.

“Indeed, the beginning of the vaccine was terror for us because we were hearing different stories,” Asibazuyo told VaccinesWork. “But ever since my community health extension worker visited our home for sensitisation and told us the truth, I changed my mind, because I used to walk over four kilometres taking my children for malaria treatment at the health centre and sometime spent over 20,000 shillings (US$7.5) on treatment of malaria when there is not medicine in the government facility”.

According to her, the two children who were vaccinated for the first and second doses have been malaria-free since June, a fact she attributes to the vaccine that she had initially hesitated to take.

Have you read?

A human bridge

Millions of families across the country have taken up their children for the malaria vaccine on the advice of the CHEWs, Dr Ronald Ocaatre, Assistant Commissioner in charge of Health Promotion and Strategic Health Communication at the Ministry of Health, told VaccinesWork during an interview at the Ministry offices in Kampala.

Ocaatre described CHEWs as the Ministry’s “bridge to the last person”, as many people in hard-to-reach areas would otherwise be cut off from the information the public health services put out in the traditional media.

“We have trained them on misinformation before even the vaccine roll-out. Those with children have gone ahead to act exemplary by initiating their children to these vaccines, and we have registered such high vaccine intakes in the West Nile region because of them.”

Ocaatre highlighted that besides creating awareness, CHEWs have been tasked with registration of infants for vaccination in communities and then follow up those that require to take second, third and the last dose.

“Even before the roll-out, we had a lot of untrue information [circulating] – and yet we have so many vaccines in use that have never caused any single problem,” he noted.

According to the Assistant Commissioner, 85% of the vaccines have been taken up across the targeted districts.

More from John Musenze

Recommended for you