“We came here for safety”: in Uganda, refugee girls find protection from conflict and cancer

At Bidbidi Refugee Settlement, each HPV jab armours an already hard-won future.

- 14 January 2026

- 7 min read

- by John Musenze

At a glance

- For the past ten years, refugee girls in Uganda have had the same rights of access to free human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination as their Ugandan-born counterparts

- A majority of the refugees at Bidibidi Refugee Settlement have fled war in South Sudan, a country which, like Uganda, sees high fatality rates from cervical cancer, but unlike Uganda, does not yet offer the HPV vaccine as routine

- “We must protect our children,” says Moses Duku, a refugee leader at the settlement. “In South Sudan we had no such vaccination. Here in Uganda, our girls have a better chance to grow healthy... We came here for safety.”

Sixteen-year-old refugee Rose Fitina says coming to Uganda gave her more than a shot at survival: it gave her the chance to dream of a future.

She was a small child when she witnessed her village in South Sudan being wiped out amid civil war. In 2016, she fled over the border; soon, she settled in at school and cultivated plans to become a nurse. Today, Zone 8, Yoyo village in Bidibidi Refugee Settlement in the West Nile region of northern Uganda, is not just a sanctuary, it’s home.

And the public health system in her adoptive country is as eager to underwrite her future as if she were born in Uganda. “Uganda has an integrated refugee policy. We do not segregate health service delivery by nationality. As long as a girl is on Ugandan soil and is ten years old, she receives the HPV vaccine,” Dr Immaculate Ampeire, Senior Medical Officer at Uganda’s National Expanded Programme on Immunization (UNEPI), told VaccinesWork.

Fitina recalls: “One afternoon in 2019, we were suddenly called out of class. We didn’t know why until we entered the room and saw health workers waiting. They told us about cervical cancer and the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine. Everyone looked confused because it was our first time hearing about it.”

They were told they could say “no” or “yes” to the jab. Trust can be a scarce commodity in displaced communities like Bidibidi, but because the health workers who began to explain the purpose of the vaccine included some South Sudanese refugees, she and many of her classmates accepted the jab.

“Some girls said all vaccines were not safe, others said it was a secret family planning method for schoolgirls, but we were sensitised by our own people. After proper education, we understood the truth, and majority accepted the vaccine,” Fitina told VaccinesWork.

“I know it will protect me from cervical cancer,” she says. “After learning more, many of us have become agents [for vaccination] within the settlement.”

As a veteran of the jab, she finds herself in a position to dispel some of the rumours about the vaccine that have been circulated. “We had been told we will not be having our monthly periods, but I get them on time and not even painful as we had been threatened.”

Have you read?

A shield

Uganda currently hosts about 2 million refugees according to the Office of the Prime Minister, with 91% in settlements coming principally from South Sudan and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). Women and children make up nearly 80% of this population.

In all three countries – South Sudan, the DRC and Uganda – women are at high risk from cervical cancer, with low rates of screening and access to care meaning a majority of the women who are diagnosed will die of the disease. But unlike South Sudan and the DRC, Uganda has already made the HPV vaccine – which has been proven capable of preventing some 90% of cases of cervical cancer – available for free to adolescent girls as part of its routine immunisation schedule.

Moses Duku, a refugee leader and a father of two, says that his role is to see that his people are safe and happy – and that means making sure eligible girls in the Bidibidi Refugee Settlement access the shield being offered to them.

“We must protect our children. In South Sudan we had no such vaccination. Here in Uganda, our girls have a better chance to grow healthy. If a parent is hesitant, we ask the child if they want the jab and then as elders sit and decide for the girl, because we came here for safety – so why deny it to one, just because of ignorance?” he told VaccinesWork.

Ten-year-old Swail Fidaya from South Sudan, also now resident in Bidibidi, got vaccinated four months ago. Fidaya was just two when her mother fled to Uganda, escaping violence in South Sudan that left her father dead.

“My mother told me about [cervical cancer] and the vaccine,” Fidaya says. “When the vaccinating team came, I was so happy because I had never heard anyone affected by it. I know about cervical cancer: it kills women only and only those that did not get this vaccination.”

Talking vaccines across language barriers

The HPV programme was a difficult one to set up, says Hindum Afakorum, the nurse in charge of Expanded Program on Immunization (EPI) activities at Jomorogo Health Centre III, a facility that serves both the refugee population at Bidibidi and the local host community.

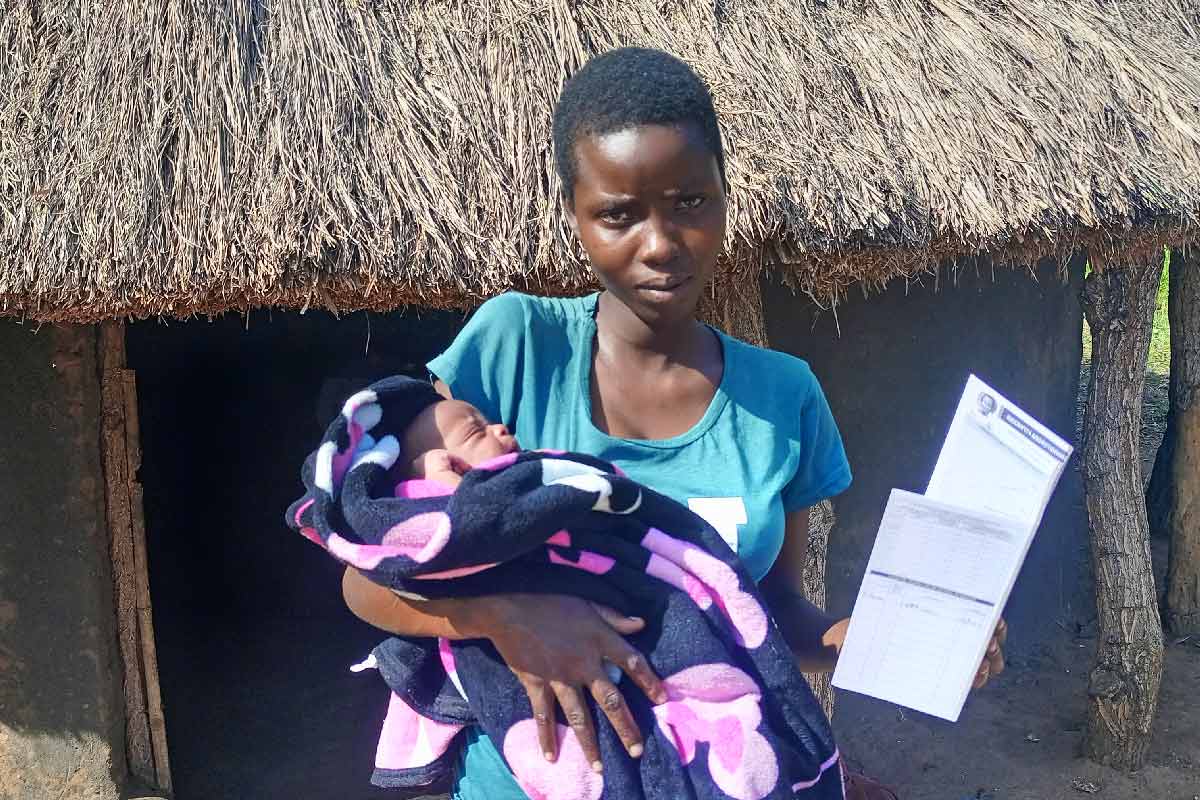

Credit: John Musenze

Language barriers, differing social norms, and high levels of vaccine misinformation and myths among refugees made for a sticky start. But Afakorum says that over the course of the decade since the roll-out to the refugee population began, the programme has picked up pace, with many parents bringing in their children unasked.

Afakorum, her colleagues and allies in the school system begin to reach out to girls and their families with information about the vaccine when the girls are nine. The target age for vaccination is ten. The biggest challenge in such a communication-heavy public health push, she says, is language.

“We begin the campaign from the age of nine, and in schools, and this is done constantly. We ask the children to go and teach their parents about the vaccine, seek consent to take it when the time comes. Some parents do not understand our explanations because we don’t speak the same languages. But after continuous education, things have improved. Many now come willingly, and others receive the vaccine during our outreach visits,” Afakorum explained.

Besides vaccination, they normally offer screening for cancer and precancerous lesions every three months. “Sadly, we have had some positive cases, and these are currently on treatment freely,” she said.

Full speed ahead

UNEPI’s Dr Ampeire says that Uganda’s HPV coverage is estimated at 100% for refugees, a figure boosted by ambitious biannual catch-up campaigns. In line with World Health Organization guidelines, the country has transitioned to a single-dose schedule from a two-dose schedule.

Dr Ampeire said UNEPI works closely with districts and refugee settlement leaders, especially village health teams (VHTs) who are typically refugees themselves. These teams help mobilise communities, translate health message, and guide outreach teams to girls who might otherwise be missed.

Unlike measles and polio, which are given immediately at refugee reception points, the HPV vaccine is administered after settlement, through facilities, schools and monthly outreach visits, Dr Ampeire explained.

“We follow the same policy for both refugees and host communities. We also vaccinate older girls aged 11 to 14 who missed doses earlier. Our programme started in 2016 and has now picked up, achieving more than even with the host communities. And this is not only with HPV vaccine but with all vaccines and immunisation programmes” she adds.

But despite those successes, challenges remain – and the refugee community is one in constant flux, meaning immunisation gaps can open up quickly. Dr Ampeire called on parents and other caregivers to give a chance to all girls, whether they are in school or not.

“Geographical access, health worker shortages, misinformation and language constraints complicate our work. In refugee communities, you may have French speakers, Arabic speakers and local dialects, but health messages are often in English, so we must take extra steps. Then girls who are not in school are often left behind from sensitisation to vaccination,” she said.