When infection sparks obsession: PANDAS and PANS

A controversial diagnosis is increasingly accepted among doctors. Finding care remains out of reach for many families.

- 15 April 2024

- 23 min read

- by Undark

When Angela Tang’s teenage son came down with a baffling illness, few households could have been better equipped to deal with it. The family lives in a wealthy Los Angeles suburb. Both parents are doctors — Tang in internal medicine, her husband in infectious disease — and their son, a straight-A student well-liked at school, had been cared for by the family’s pediatrician since birth.

Still, the parents worried as their son’s symptoms appeared, seemingly out of the blue, in September 2018: He'd meticulously line up pencils in groups of five, recite prayers unrelentingly, make homework illegible as he had to erase or cross out every C, D, and F.

Eating, too, became a chore. If he had a contaminating thought while taking a bite, he’d have to spit out the food, wash his mouth, and try again, but the new bite couldn’t have touched the old one. It got to the point where he could only eat mushy or semi-liquid foods carefully placed “in little aliquots on his plate, so that if one bite got contaminated,” it wouldn’t touch the others, Tang said. Before long, she and her husband were working around the clock just to get him through the day.

In a panic, Tang consulted their pediatrician, and recalls the doctor asking an intriguing question: “Has he had any unusual infections recently — because you know about PANDAS, right?”

At the time, Tang knew nothing about PANDAS. She had completed her own medical residency two years before the illness — short for pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections — was first outlined in a 1998 paper. That publication detailed how a child’s behavior could change alarmingly after a strep infection, and may include symptoms of obsessive-compulsive behavior and tics. It has also stirred controversy: Many doctors hesitate to diagnose or treat the condition even today.

Talking with their pediatrician then, Tang and her son could not recall that he had had any “unusual” infections. (Undark is not naming Tang’s son because of the sensitive nature of his health diagnosis.) But his obsessive-compulsive symptoms had become unmanageable. “I need medicine. I need therapy. I need whatever you could throw at this,” Tang recalled telling the doctor, who provided a list of psychiatrist referrals. None would accept new patients or return her calls, Tang said. Meanwhile, the boy worsened.

Tang confided their struggles with a medical school friend; the friend consulted her mother, a semi-retired pediatrician, who had a similar premonition: They should rule out PANDAS.

But ruling out PANDAS isn’t easy. After several decades, the illness still eludes mainstream medicine. PANDAS spans multiple body systems and medical specialties. In 2010, a group of clinicians and scientists defined a broader category — pediatric acute-onset neuropsychiatric syndrome, or PANS — which includes PANDAS as well as sudden OCD (or severe eating restriction) that could be associated with other types of infections, or with inflammation triggered by other causes.

In the United States, as many as 1 to 3 percent of children and adolescents have OCD, and researchers estimate that 5 percent of these cases meet criteria for PANDAS or PANS. For numerous reasons — including the suddenness and severity of psychiatric symptoms, lack of a definitive lab test, and the siloed nature of health care in the United States — time-pressed physicians struggle to help patients with these illnesses. Both misdiagnosis and missed diagnoses are common.

But awareness is growing, and some doctors seem to be less dismissive. "I think it is starting to get more respect,” said Tempe Chen, a pediatric infectious disease physician at MemorialCare Miller Children’s and Women’s Hospital Long Beach in California.

“There are a lot more people who are highly respected in the field, not deemed ‘quacks,’” she added, “that are highlighting that this is something very real that needs to be further explored and investigated and appropriately treated.”

The idea that immune responses to infections could trigger OCD traces some of its roots to a childhood “dance mania” initially observed centuries ago in medieval Europe. In a 1686 book, the British physician Thomas Sydenham described boys and girls limping and convulsing uncontrollably — stricken with a condition known now as chorea, from the Greek choros meaning dance. Later, scientists recognized Sydenham’s chorea as a neurologic complication of rheumatic fever, an inflammatory autoimmune condition that develops in some children after a strep infection.

Though initially defined by movement abnormalities, many people with Sydenham’s chorea have psychiatric symptoms as well. “Children who, previous to the onset of chorea, were quiet and manageable, suddenly became restless, irritable, extremely sensitive and abusive,” a psychiatrist at the University of Colorado wrote in the Journal of the American Medical Association in 1926. Sydenham’s chorea is less common today, but when it does occur, some 60 to 80 percent of children with this disease also have obsessions and compulsions.

“There are a lot more people who are highly respected in the field, not deemed ‘quacks,’ that are highlighting that this is something very real."

OCD can be a disabling illness — even more so back in the early 1990s when its biological roots were poorly understood. It was around that time that Jesse, as an elementary school student in Connecticut, found herself incessantly clearing her throat and spitting in the middle of the classroom. “I couldn’t touch people because I felt like I would get demons in me or ‘bad energy,’” Jesse said in a recent interview with Undark. (Jesse asked that her last name be withheld due to concern over public disclosure.) And “if I did feel there was a bad energy in me or some kind of bad force, I would have to spit — which is really embarrassing as a kid in school,” she added. Jesse knew how bad it looked, "but I couldn’t not do it.”

In the mid-1990s, at the age of 12, Jesse was admitted to Yale New Haven Hospital, where psychiatrist James Leckman treated children with OCD and tic disorders. (Leckman has co-authored more than 200 research papers on these illnesses.) By that point, the girl had spent years with tutors, therapists, psychologists, and psychiatrists — to no avail. At Yale, Jesse received further psychotherapy and several medications for behavioral and movement disorders. Still, nothing seemed to result in lasting improvement.

What stood out to Leckman were “things like the sudden onset and the complexity of the presentation” — and her positive strep test. Jesse’s unusual symptoms bore some resemblance to four 10- to 14-year-old boys being studied in a National Institute of Mental Health trial. As described in a 1995 paper, the boys had a newly recognized subtype of sudden-onset OCD or tic disorder that develops after infections, much like Sydenham’s chorea. They received immunological treatments, consistent with the idea that Sydenham’s stems from an autoimmune process, where antibodies mistakenly attack the brain. All showed clinically significant improvement immediately following treatment.

Leckman discussed with Jesse’s family the possibility of a treatment called plasma exchange that had helped two boys in the NIMH study. After several rounds of the procedure, which can be used to rid the blood of plasma containing harmful antibodies and replace it with healthy plasma, Jesse’s tics and obsessive-compulsive behavior improved, and she “conducted herself with better humor, spontaneity and independence,” the researchers noted in a 1996 case report.

The NIMH boys were among the landmark 1998 report on the first 50 PANDAS cases. Jesse was “patient zero” for Leckman’s team. While he is no longer active as a treating clinician, Leckman estimates that since Jesse, his team treated about 10 PANDAS patients per year. Her case “started me down the PANDAS/PANS road in earnest,” Leckman noted in an email.

Today, Jesse still takes Prozac for extreme anxiety and OCD, and the 42-year-old owns a house and has a long-term partner. “I’m definitely a lot more stable,” she said.

After a round of antibiotics, Tang’s son also enjoyed a period of stability. It lasted 10 days. Then he slipped again — hard and fast.

He couldn’t walk in a straight line; Tang remembers it taking 45 minutes for him to go two blocks home from the bus stop because he had to divert his path each time he saw a mark on the ground. At school, he was late to classes and once had to be escorted off the quad by the nurse because he couldn’t find his way out.

At some point, Tang came across the PANDAS Network, a national advocacy group, and contacted the founder, Diana Pohlman. Pohlman, who lives in the San Francisco Bay Area, started the group in 2009 after her son developed PANDAS.

On the phone, Tang was “just like any other mom — really, really, really scared,” said Pohlman, who receives dozens of emails, texts, and calls per month — mostly from parents “whose kids flip out” but also from doctors who see suspected PANDAS and want guidance.

Pohlman took Tang’s panicked calls and went over key research showing how the immune response to an infection could send autoantibodies into the brain and cause odd behavior — and which treatments may help. She “shepherded us through the illness,” Tang wrote in a follow-up email.

Have you read?

Pohlman was “excited because I’m a doctor in LA” and could potentially help local families, Tang recalled. However, with her own son barely eating or drinking and unable to swallow pills, “I’m a mess right now,” she told Pohlman in the fall of 2018. “I’ll help you as soon as my kid’s better.” In the coming years, Tang made “more than good on her promise,” Pohlman said.

Tang and her son eventually connected with Nicole Cobo, a local neurologist in Long Beach who squeezed him in “as a favor to my pediatrician,” Tang said.

Cobo was taking a risk. At the time, her neurology practice did not treat such patients, consistent with the common sentiment in their field. "I don’t know if ‘voodoo’ is the right word, but that’s kind of what comes to mind,” she said. Although the practice has become more open-minded about suspected PANDAS cases, at the time, “our staff was told, if anybody's calling for a consult for PANDAS, tell them we don't see that.” But Cobo was moved by Tang’s son’s predicament — so much that she broke convention and made special arrangements for his care.

Those arrangements depended on Chen, the pediatric infectious disease physician in California. During her medical training in the 2000s, Chen had a “peripheral idea” of PANDAS. Mainly she knew “it was controversial.” But years later, when several of her patients had concerning symptoms that looked like PANDAS, she began to take it more seriously. When Tang’s son came along, Chen remembers Cobo telling her, “If there was someone that was going to make me believe that this syndrome is real, it’s this kid.”

Tang carried a copy of the PANS treatment guidelines in her bag and had already researched and discussed with Pohlman the treatment she felt that her son needed: IVIG, where a patient receives intravenous infusions of antibodies pooled from thousands of healthy donors.

Similar to plasma exchange, the immune therapy Jesse received in the 1990s, IVIG, or intravenous immunoglobulin therapy, reduces inflammation. Some of the donor antibodies may stick to the patient’s “bad” antibodies — which attack healthy cells — and inactivate them, Michael Daines, an allergist-immunologist at the University of Arizona, wrote in an email to Undark. And “by flooding the immune system with IVIG,” he added, “you can make some of your inflammatory cells essentially turn off and stop the production of inflammatory signals.”

While it’s hard to know which exact mechanisms are at play, Daines noted, IVIG is FDA-approved for some autoimmune and neurological diseases, and recommended for a condition associated with Covid-19 called multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children. Doctors routinely administer the infusions to people with autoimmune encephalitis, where antibodies attack brain cells, leading to inflammation.

“Our staff was told, if anybody's calling for a consult for PANDAS, tell them we don't see that.”

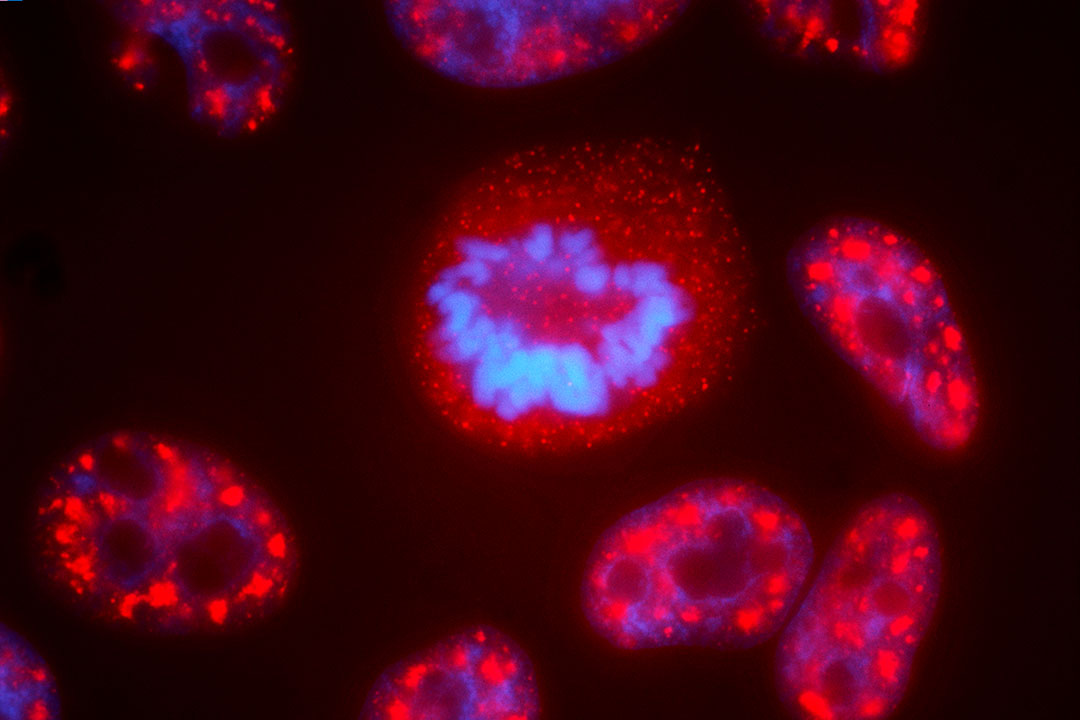

Whether PANDAS, or the broader PANS, is a form of autoimmune encephalitis is debatable: Some who study or treat this disease say it is, others who are unfamiliar are less sure. By and large, scientists and clinicians acknowledge the general phenomenon: Autoimmune diseases of the brain can develop when the immune system generates antibodies that mistakenly attack proteins in the brain. But until recently, there was no evidence for how anti-strep antibodies could gain access to the brain, which is typically shielded from immune proteins by the blood-brain barrier. Dritan Agalliu, a neuroscientist at Columbia University, helped usher in that discovery: He collaborated with researchers at the University of Minnesota Medical School to lead a set of experiments. They found that a set of immune cells, called Th17 cells, that were known to cause trouble in multiple sclerosis and other autoimmune diseases, can in fact enter the brain through the nose and cause a breakdown of the barrier. In mice with autoimmune encephalitis, his lab found that this breakdown allows “the infiltration of pathological antibodies in the brain.”

In the blood of children with PANDAS, Agalliu’s team found high levels of proteins called cytokines that mediate inflammation. He noted in an email that the findings, which were published as a preprint and are currently undergoing peer review, “demonstrate that the disease has an inflammatory nature.” And a team led by Yale researchers found that antibodies from PANDAS patients target a specific type of brain cell associated with tics in humans and repetitive behaviors in mice.

More recently, some case reports suggest the possibility of PANDAS in young adults, and researchers in Canada found that more than half of study participants in a pediatric eating disorder program met criteria for PANS.

“Like a lot of things in medicine, you’re not going to have the one study that proves it. But there’s so much data,” said Jennifer Frankovich, a Stanford pediatric rheumatologist who was senior author of a recent review on Sydenham’s chorea, PANDAS, and PANS. “When you take all of it together, it’s hard to refute it.”

But “critics aren’t reading all this,” said Frankovich, who directs the Stanford PANS program. “If you don’t believe it’s real, you’re not going to sit down and spend weeks reviewing all the literature.”

When it comes to actually treating PANDAS/PANS, much of the hesitation stems from lingering confusion over how to diagnose it. “We can’t do a blood test and say, oh my gosh, this is really out of whack,” said Laura Pace, an adjunct assistant professor at the University of Utah who specializes in neurogastroenterology and autonomic disorders. Although there is a series of tests, called the Cunningham Panel, that is supposed to help clinicians distinguish PANDAS/PANS cases from non-autoimmune OCD patients, it costs $995, and at least one study raises questions about how well it works.

Ultimately, doctors make their best judgment based on the patient’s medical history and recent symptoms, which can overlap with other conditions such as OCD, autism, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and other childhood tic disorders.

One notable characteristic of PANDAS/PANS is the rapid appearance or worsening of symptoms, with severity that rises and dips unpredictably. Yet even these features may not be unique, some physicians note. “Many neurologic diseases, for example, epilepsy, begin suddenly and dramatically,’” wrote Donald Gilbert, a pediatric neurologist at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, in a 2019 commentary.

Another criterion for diagnosing PANDAS is an associated strep infection. The trouble is, strep can sometimes be cleared from the throat within several days, said Frankovich, which means a diagnosis might get missed if a kid doesn’t get the workup at the right time.

Plus, the lag time between infection and symptoms can be weeks to months, so for any individual case, “you can never, ever say this infection caused this disease,” Frankovich added.

“You can’t, because everybody gets infections. There’s a hundred strains of strep. Strep is going around the school all the time. If you look at any kid’s history, they had strep.”

In the field of psychiatry, where many diagnoses are descriptive rather than lab-based, PANDAS poses particular challenges because its symptoms wax and wane, and manifest differently from patient to patient. There is “a set of symptoms that you need to meet before you meet the criteria,” Leckman said. This is “problematic in terms of really having a deeper understanding of what the nature of the condition is.”

But the bigger problem may be the presence of psychiatric symptoms at all, which often trigger “automatic hands-off skepticism from the other medical doctors outside of psychiatry,” Cobo said. She and her neurology colleagues, for example, are not trained well to cover both physical and mental health, she said, so when they interact with psychiatrists “there’s a lot of ‘that’s your space and this is mine,’” yet PANDAS really straddles both. “That makes it hard for these patients to get good, well-rounded care.”

When “we’ve lumped it under this post-streptococcal umbrella and called it PANS, and PANS started getting linked with every child who has tics, I think that’s where we’ve gone wrong.”

Overdiagnosis and misdiagnosis are also concerns, as reflected in Reddit posts and in an episode of the American television series "Chicago Med." “Us doctors get really tired when these parents show up and say, oh, my child has tics” — which affect as many as 20 percent of school-age children — “and they had a sore throat and this must be PANDAS and you have to do this whole big workup,” Cobo said.

The underlying idea — that an immune response to an infection fails to calm and instead starts to attack normal organs — is “not foreign to any doctor no matter what their specialty,” Cobo said. But when “we’ve lumped it under this post-streptococcal umbrella and called it PANS, and PANS started getting linked with every child who has tics, I think that’s where we’ve gone wrong.”

Even as Tang navigated her own son’s diagnosis and treatment, she understood why many of her physician colleagues might refuse to see a patient with suspected PANDAS. Families “will be desperate. They just kind of lost their kid in a really horrible way,” she said. And since symptoms can fluctuate day to day, “they’re going to be spamming you on your phone line, on your MyChart, on whatever it is that you use to communicate,” she said. Dealing with the disease is “a time suck,” she added. “And if you’re a caring physician, it’s a soul suck.”

Since seeing Tang’s son, Chen, the pediatric infectious disease physician, has received around five additional referrals for possible PANS or PANDAS, but clinics are generally limited in how many patients they can take, Chen said. "It's very challenging to diagnose because there's no one specific test. It's a cluster of symptoms — it’s how those symptoms manifest. There are so many complexities to making sure that PANS or PANDAS is what you think the patient has, and then trying the various different treatments.”

Dealing with the disease is “a time suck,” Tang said. “And if you’re a caring physician, it’s a soul suck.”

Treating the patient could mean prescribing antibiotics when there is no documented infection, which goes against many doctors’ training and experience. The American Academy of Pediatrics’ Red Book, which Chen said is “like our Bible” for treating infectious diseases, states that evidence is “insufficient” for offering antibiotics or IVIG to children with suspected PANDAS or PANS. It also advises physicians to not test for strep if the patient has no obvious symptoms.

Scientists and physicians on the PANDAS Network advisory board disagree with these recommendations. In November 2020, they emailed David Kimberlin, editor of the Red Book, and Kyle Yasuda, a former AAP president, to request revision, suggesting it “is irresponsible” not to offer a strep test to patients who present with sudden PANDAS symptoms without a sore throat. Nothing came of the letter, Pohlman said. Although a new edition of the Red Book will be published this spring, it’s unclear whether this guidance will change. Undark made multiple attempts to contact several Red Book editors but did not get a reply.

When Tang’s son saw the pediatrician, his throat swab was negative for strep. Later, though, Tang recalled that both she and her son did have sore throats, which improved on their own without treatment. They also learned that a classmate in close proximity to her son had been ill around that time and was diagnosed with a strep infection.

Since PANDAS and PANS are rare and newly documented, solid evidence supporting IVIG use for these disorders is limited. Perhaps the most compelling study was published in 1999 in the medical journal The Lancet. This study enrolled 30 children with severe, infection-triggered OCD or tic disorders. Ten received a placebo, and 20 got IVIG (or the related treatment plasma exchange). Among the 17 treated participants who completed the study, 82 percent maintained improvement after a year of follow-up.

A small number of other studies have looked at these immune-modulating treatments in PANDAS/PANS. However, due to low patient numbers and design flaws — for example, allowing participants to receive additional IVIG doses if they didn’t improve on the first — all of those studies “have to accept that their results can be negative,” wrote Daines, the allergist-immunologist at the University of Arizona.

To shore up the evidence base, he and colleagues are enrolling 92 children with diagnosed PANS in Italy, Sweden, and the U.S. for a trial sponsored by Octapharma to test the company’s IVIG versus placebo. (Many trials of this size have financial backing from private companies.) As part of this study, the participants will receive three infusions — either saline or IVIG — three weeks apart, and then cross over to get the other treatment. Daines noted the design will allow them to study the effects of multiple doses of IVIG: “If there is a response, we will be able to see it.”

With the evidence unsettled, IVIG has logistical barriers: The infusions are costly and often not covered by insurance since the therapy is not FDA-approved for PANDAS/PANS.

Lynn Ashley, a registered nurse in Frenchtown, Montana, found a doctor willing to administer IVIG for her daughter, who was diagnosed with PANDAS in 2010 at the age of 11. The infusions, Ashley recalls a doctor telling her, would cost $30,000 to $50,000 “and we would have to pay out of pocket."

“We were actually thinking we’re going to just get a second mortgage on the home,” she added, and her family had the paperwork drawn up.

Indeed, IVIG “is expensive,” wrote Daines. “But so is untreated disease with out-of-control OCD, behavior problems, and family disruption.”

After finding another doctor, Ashley’s family was stunned to learn, on the day their daughter went in for IVIG, that their insurance coverage did come through. After initially refusing, the insurer agreed to cover the treatment after the physician fought back with documentation from an urgent care visit that clearly tied a strep infection to their daughter’s psychiatric symptoms, Ashley said.

“We were actually thinking we’re going to just get a second mortgage on the home.”

In the case of Tang’s son, when his situation became dire and he stopped eating or drinking, he was able to receive IVIG with insurance coverage. Two key factors helped. First, he received IVIG as an inpatient. “Insurance companies will usually not be able to fight that as much because it was part of a hospitalization,” Tang said. Second, instead of charting the diagnosis as PANDAS or PANS, it was coded as “autoimmune encephalopathy” — a broader disease category for which IVIG is a standard treatment.

After four rounds, he was well enough to return to school.

He was the “luckiest of the luckiest of the luckiest kids,” Tang said of her son.

“We were able to pull backdoor strings to get appointments,” she added, “and get people to believe me, and to get him admitted.”

Like Long Covid, multiple sclerosis, and other illnesses tied to past infections, PANDAS faces obstacles derived from the structure of U.S. health care. Since there is no definitive lab test to diagnose the disease, patients must consult multiple specialists — yet few are incentivized to spend the time it takes to wade through a complicated history. “Medicine in the U.S. is highly siloed,” said Pace.

“Especially in fields in which we can earn a lot of money doing procedures,” she noted, “they don’t want us applying the time it takes to do the cognitive component of medicine for these conditions.”

At the Stanford Immune Behavioral Health Clinic — formerly known as the Stanford PANS Clinic — the intake visit is usually two hours “to get the story right,” said Frankovich. “Our physical exam is an hour. We spend a lot of time characterizing these kids. Then we have a meeting.” Most general pediatricians have 15-minute appointments, she added, so “how can you put all this together?”

Seeing patients with complex conditions like PANDAS can also create a lot of administrative red tape. For medical practices that must field prior authorizations and insurance appeals, that can become costly, Pace said, and rather than treat those patients, some doctors “would just rather not have them.”

Some of this comes down to the culture of medicine, which is said to blend art and science but has veered more toward the latter as clinical decisions depend increasingly on evidence. In the absence of solid evidence, “some of the feedback that I get from physicians is, well, our oath is to do no harm,” said Pace. “What they fail to recognize is that doing nothing is harm.”

Doctors nowadays "rely very heavily on what the labs tell us, what the imaging tells us, what all the studies tell us,” said Cobo, the neurologist who treated Tang’s son. Yet diagnosing PANDAS or PANS relies heavily on the medical exam and history — what was the patient’s baseline? How acute was the change? What are their current symptoms?

That “can be an hour-long visit,” said Cobo. Unfortunately, though, the insurance reimbursement system incentivizes physicians “to crank through a high number of patients,” she said, rather than spend time with them.

Sarah Cueva, a Bay Area pediatrician at a concierge practice, charges patients directly rather than contracting with insurance companies, so she’s able to spend more time with families, and often draws tough cases who “need extra help with their primary care.” Although she did not learn about PANDAS as a medical student or trainee, Cueva thinks she has been “less skeptical than others, and that's probably why I find cases — because I'm looking for them.” She has also refuted PANS and PANDAS in many patients, telling them it “sounds more like ADHD and anxiety” or another diagnosis.

“How many people walking around in the world who we see as psychotic or mentally ill or crazy, who are nonfunctional, might have an inflammatory brain disorder?”

Among a dozen or so PANDAS/PANS cases she has seen in the last decade, one patient — a physician colleague’s daughter — made a lasting impression. The girl developed sudden struggles with toileting and eating, and refused to leave the house — screaming and throwing things and prompting neighbors to call child protective services. At Cueva’s office, she made no eye contact and obsessively repeated a phrase and action, “like she was stuck on a loop.” Then, after starting a course of naproxen, an anti-inflammatory drug, “a switch flipped,” Cueva said. She “went back to herself.” The experience left Cueva to wonder, “how many people walking around in the world who we see as psychotic or mentally ill or crazy, who are nonfunctional, might have an inflammatory brain disorder?”

Modern medicine focuses on the physical body and tends to separate “behavior and emotions into this other domain of medicine,” Pace said. “We forget that we’re one complex system driven by biological mechanisms.”

Meanwhile, the Covid-19 pandemic has acclimated physicians to the possibility of post-infection psychiatric symptoms in children, and grassroots operations are raising awareness of PANDAS and PANS in particular. Several years after Pohlman launched the PANDAS Network, one of her neighbors co-founded the PANDAS Physicians Network, which focuses on equipping medical providers to recognize and treat PANS/PANDAS. The network’s directory has about 350 clinicians from various specialties — including pediatricians, nurse practitioners and therapists — who are familiar with PANS/PANDAS, said executive director Susan Boaz.

Some of these clinicians have firsthand experience navigating the health care system for their own children with PANDAS. Remembering her promise to Pohlman to help the field once her son improved, Tang teamed up with a dozen of them to publish a paper describing barriers they encountered while trying to seek treatment for their children. “Even among the medically sophisticated, PANDAS/PANS diagnosis and treatment remains challenging,” they wrote. Furthermore, difficulty accessing care is associated with longer-lasting symptoms and poorer outcomes.

“It's sad,” Chen said, “because it does feel like in many ways, it becomes a diagnosis of the upper middle class to the rich, because those are the only people that can afford these doctors that only accept cash payments.”

To expand access, Tang is working with local teachers and health care professionals to push for state legislation to get IVIG and other medications covered for children with PANDAS/PANS. Last year, she wrote a bill that received nearly unanimous bipartisan support through different committees but got vetoed by the California governor. The bill just got re-introduced in February. At least eleven states have already passed similar laws, and more than a half dozen others have legislation in progress.

Tang and others are also working hard to educate colleagues. In her view, it used to be that many physicians and trainees had not heard of PANDAS/PANS, and half of the ones who were aware of these diagnoses considered them controversial. “Now almost everyone has heard of it, and a minority will question its ‘realness,’” Tang said.

Written by

Website

This article was originally published on Undark on 3 April 2024. Read the original article.