Vaccine profiles: Group B streptococcus (GBS)

Group B streptococcus is one of the biggest killers of newborns in both wealthy and disadvantaged countries alike; now we are closer to a vaccine that could save thousands of lives every year.

- 15 August 2023

- 4 min read

- by Gavi Staff

Factfile: Group B Streptococcus

- Type: Group B streptococcus bacteria

- Symptoms: GBS is associated with maternal sepsis, stillbirths and preterm births, with the highest incidence in neonates and young infants up to the age of three months.

- Mortality rate: Overall 8.3% (Infant mortality estimates are seven times higher in WHO's African region)

- Annual cases: Invasive GBS 392,000, neurodevelopmental impairment 37,000, GBS-associated pre-term births 518,000.

- Annual deaths: 91,000

- Geographical range: Worldwide, but the highest rates of infection in pregnant people are found in sub-Saharan Africa, and in Eastern and South-Eastern Asia.

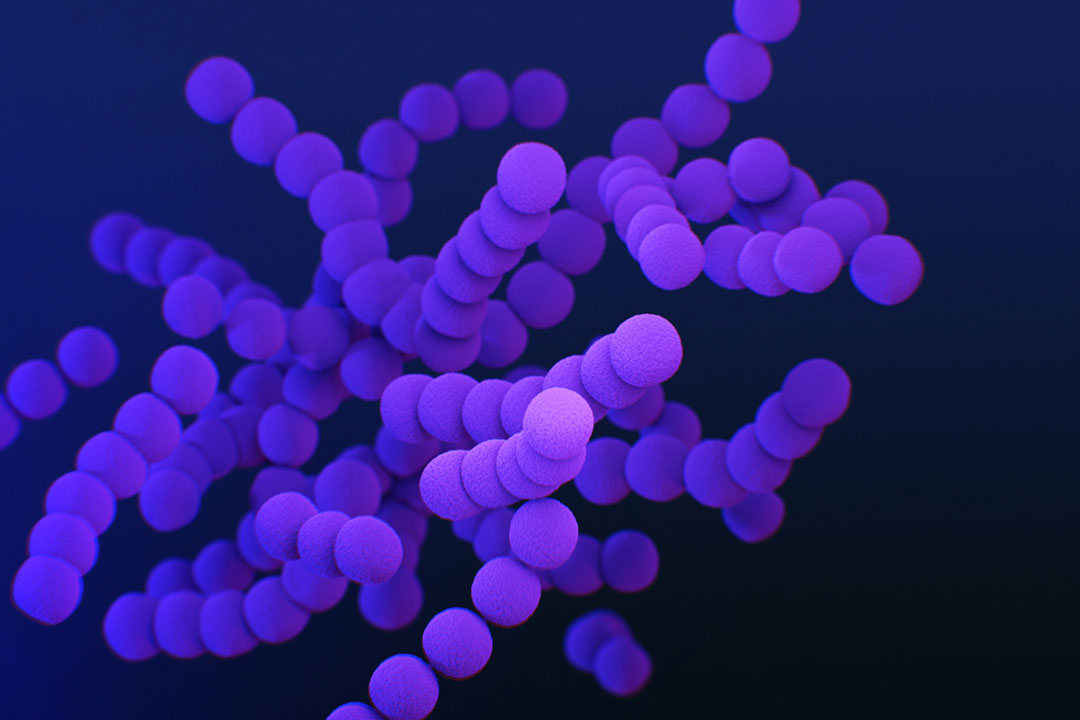

In many people, Streptococcus agalactiae or Group B streptococcus is a roundish bacterium drifting along in chains through our body, part of the microbiome of bacteria that co-exists harmlessly inside us, including in around one in five pregnant people.

However, in babies, both in the womb and outside, this mostly benign bacterium can turn deadly killer, causing pre-term births or stillbirths.

While the biggest risk is to babies, it can also affect elderly people or those who are immuno-compromised.

Even when newborns survive the birth, they can still become very ill with meningitis (when the meninges, the thin lining covering the brain and spinal cord, becomes infected), or sepsis (blood poisoning, that can trigger tissue damage, organ failure, and death).

Group B streptococcus (GBS) can also cause pneumonia, which kills more children each year than any other disease, causing pre-term births, stillbirths and neonatal deaths.

Group B Streptococcus disease

The bacteria has ten different serotypes, with 1a, 1b, II, III, IV and V causing the most disease. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), GBS was estimated to have caused 392,000 cases of neonatal disease annually in 2015, causing 91,000 deaths and at least 57,000 stillbirths. Africa by far bears the highest burden, as it has 54% of estimated invasive GBS cases, and 65% of all infant deaths.

While the biggest risk is to babies, it can also affect elderly people or those who are immuno-compromised.

As there is no licensed vaccine yet, in high-resource countries, pregnant people are screened for GBS colonisation and given prophylactic antibiotics (penicillin). This is more than 80% effective in the prevention of early-onset disease in infants (up to six days of age) but not against late-onset disease (seven to 89 days) or prebirth sequelae associated with group B streptococcal infection.

Have you read?

Yet there are challenges with this approach. Not only do pregnant people in low-income countries rarely have access to this preventive treatment, the overuse of antibiotics could drive antimicrobial resistance to penicillin even higher, thus a vaccine could go some way to mitigating this.

WHO's Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunization (SAGE) has declared it a priority to develop a safe, effective and affordable vaccine available for global use to prevent GBS-related stillbirths and invasive GBS disease in neonates and young infants and reduce the impact on AMR by lowering prophylactic antibiotics use.

Challenges in vaccine development and feasibility implementation

While efforts have been underway to develop a GBS vaccine for decades, the complexity (and sometimes, reluctance) to test a vaccine in pregnant people, understanding the timing of vaccination during pregnancy, and needing to ensure that immunity would be passed onto newborns, have slowed vaccine development.

The education and awareness of spouses and health care workers around maternal immuniSation and the benefits conferred to both the mother and neonate are critical in ensuring acceptability as well as access to the vaccine once available.

In addition, the sheer scale of the health threat posed by the bacteria had been underestimated until a key study by WHO and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) in 2017which was incorporated into WHO's Full value of vaccines assessment in 2021, and a Lancet paper in 2022.

Progress towards a working vaccine

Two vaccines are currently under clinical development, one with Pfizer and the other with MinervaX.

Pfizer's GBS vaccine candidate, GBS6, is in phase 2 testing for safety and immunogenicity in healthy pregnant people aged 18 to 40 years, who were vaccinated during the second or early third trimester of pregnancy. The vaccine is a hexavalent anti-capsular polysaccharide (CPS)/cross-reactive material 197 glycoconjugate (GBS6). GBS6 is designed to offer protection against the six most prominent GBS serotypes, which account for 98% of disease worldwide.

The trial is ongoing in South Africa, the UK and the US. The vaccine had such promising interim phase 2 results that the US Food and Drug Administration granted it "breakthrough status" to expedite its development and review. In a paper in the New England Journal of Medicine in April 2023, results showed that immunoglobulin G responses to all six serotypes were elicited, and this was sustained through delivery and transferred to infants.

Danish biotech company MinervaX is developing a vaccine based on antigens derived from the surface proteins of the bacteria that should cover almost all clinical GBS isolates. The company has just completed enrolment and dosing of its vaccine across Denmark, the UK and South Africa.

The vaccine had previously been given to non-pregnant people and shown to be safe, and trigger a strong immune response. MinervaX's vaccine is also in phase 1 clinical study in older adults of its novel GBS vaccine, at CEVAC (Centre for Vaccinology) in Ghent, Belgium.