Women’s water burden rose as COVID lockdowns hit

Rising demand for water collection in poor countries added to womens’ burden. Water, sanitation lacking in health, quarantine facilities – survey. School closures also limited access to these basic services for girls.

- 5 May 2022

- 4 min read

- by SciDev.Net

Demand for household water increased by as much as a third during pandemic lockdowns, forcing girls and women to spend more time searching for water for families without access to running water, analysis shows.

COVID-19-related restrictions highlighted inequalities in access to safe water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) in the Pacific Island countries, which have some of the world’s lowest rates of access to drinking water and sanitation services.

“Women’s water burdens have always been heavy and anecdotal evidence indicates that they remain that way in Pacific Island countries,” says Vivian Castro-Wooldridge, senior urban development specialist at the Asian Development Bank’s Pacific department.

“Additional burdens have come from women looking after children and other family members spending more time at home due to lockdowns, meaning more water is used and therefore must be collected and managed,” Castro-Wooldridge said.

“Women are not only the ones who carry the water, but should be, in their own right, those who are in decision-making.”

Brenda Rodríguez Herrera, Gender and Environment Network, Mexico

“This is particularly the case in informal settlements and rural communities that lack piped water, as men are generally reluctant to undertake water-related tasks because they are seen as women’s duties.”

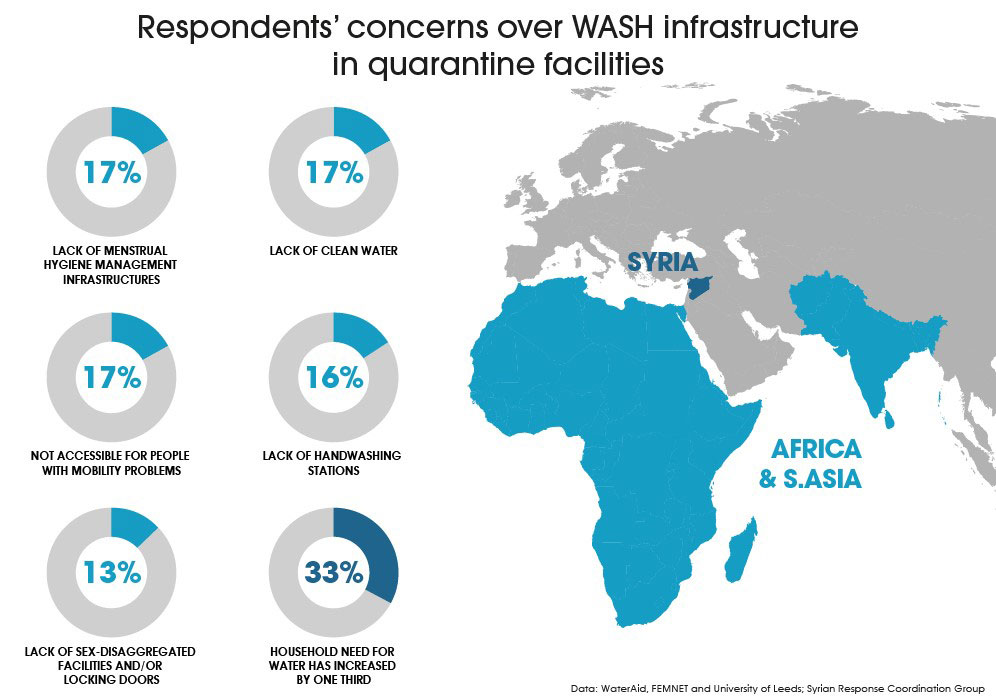

Researchers asked people in 14 countries in Africa and South Asia about their biggest concerns regarding water, hygiene and sanitation during lockdown periods. More than half of respondents said no communal WASH facilities were available, accessible or secure.

The survey was conducted by WaterAid, with the University of Leeds and the African Women’s Development and Communications Network (FEMNET). Respondents expressed concerns over water and sanitation infrastructure not only in public spaces, but also in healthcare and quarantine facilities, pointing out the lack of clean water and handwashing stations.

Just five per cent of people said hygiene services at quarantine facilities were adequate. One in seven people said facilities were not gender segregated, while 17 per cent said there was a lack of menstrual hygiene management infrastructure.

Rising need for water

SciDev.Net analysed the impact of the pandemic on women in three countries in the Middle East and North Africa, particularly in countries experiencing conflict. In Yemen, water management has become a challenge for many women, especially in rural and remote urban areas. Women in Syria face a similar situation, particularly for those living in camps for refugees and internally displaced people.

Somaya Al-Hussein, 34, was displaced from the Syrian city of Maarat al-Numan to a camp near the Syrian-Turkish border.

Have you read?

“Women go from the early morning with their plastic pots to the tanks to carry water on their heads,” Al-Hussein told SciDev.Net.

Al-Hussein and her 12-year-old daughter have to go daily to fetch water from the main tank in the camp, which is more than 500 meters from their tent. They need about 200 litres of water for their family of five, but demand for water rose significantly with the need for greater hygiene during the pandemic and they now need to find an extra 100 litres every day.

In Syria as a whole, household need for water rose by 33 per cent during the pandemic, according to data from the Syrian Response Coordination Group.

Emergency and pandemic management

In Africa, many girls rely on their schools for access to water and school closures had a significant impact on their hygiene, according to Murielle Elouga, programme officer at the Global Water Partnership in Central Africa.

“COVID-19 has, to a certain extent, negatively influenced access to water for young girls whose only opportunity was the school environment to have access to water for their personal and domestic needs,” said Elouga.

Brenda Rodríguez Herrera, from Mexico’s Gender and Environment Network, says that water management is often not considered from a human rights perspective, much less from a gender perspective. “Women are not only the ones who carry the water, but should be, in their own right, those who are in decision-making,” Rodriguez Herrera said.

COVID-19 has shown that gender must be integrated into future emergency water and sanitation policies and programmes, said Desideria Benini, a researcher who worked on the WaterAid survey.

Benini said that incorporating gender into pandemic and emergency responses would “not only save more lives regardless of social differences, but also address the root causes of people’s vulnerability, ensuring equitable, universal and sustainable access to WASH”.

Author

Riad Mazouzi, Béatrice Longmene Kaze, Neena Bhandari, Aleida Rueda, Sonya Al-Ali and Adel Aldaghbashy

Website

This article is republished from the SciDev.Net under a Creative Commons license.

This piece was produced by SciDev.Net’s Global desk.

*This article was edited on 3 May, 2022 to clarify a quote from Vivian Castro-Wooldridge about the water burden in Pacific Island countries and remove a quote by Mark Love of the International Water Centre which was taken out of context.