12,000 kilometres towards polio eradication’s last mile

How the Rotarian behind the viral #LondonToLagos motorbike ride crossed continents to remind the world that the road to polio eradication won’t stay open forever.

- 14 July 2022

- 7 min read

- by Maya Prabhu

One day in late April, not two weeks after he had set out from London, Kunle Adeyanju found himself face down in the Moroccan Sahara, his head tucked under the skeleton of his motorbike, bracing against a violent red wind. It was possible, he thought, that he had arrived already at the premature end of his adventure; he might be buried alive here, or be lifted clean off the earth, still clutching at the chassis of his Honda. The sand beneath him burned even through his thick protective clothing; the sand above him and all around him blasted and whipped in the air. “I saw death coming,” he recalls.

He lay there for over an hour, he says – though “it seemed like maybe five days, to me” – and then, at last, the sandstorm let up. Death vanished like a called bluff, like a mirage. He stood, shook the sand from his helmet, brushed away some unexpected tears, and got back in the saddle. He still had a very long way to go.

The ride wasn’t supposed to be easy. It was a bucket-list ambition: London to Lagos, solo on two wheels, impelled by the same daredevil itch that had sent Adeyanju up Mount Kilimanjaro twice before.

But this adventure had been folded into a soberer, larger mission: ending polio. Adeyanju’s portion of that fight was to fly the flag – quite literally, sometimes. At national borders he stopped to unfurl an “End Polio” banner and take a selfie for the tens of thousands, soon hundreds of thousands of followers tracking his journey on social media.

On rest days he met with vaccinators, volunteers, health policy-makers, survivors. The message was plain: he was keeping on, covering ground, and so should the campaign. More than that, he hoped his personal grit would model the energy and resolve he wanted to rouse for this tough last mile of the decades-old struggle to eradicate the paralysing virus.

“It’s all about movement, you know? It’s all about the opportunity, the grace, that my body can carry me on a bike to do this thing,” he says. “This beautiful world – coming into this world and not exploring it, I think it’s a waste.”

“For me, you see, polio is a personal fight,” Adeyanju, a Rotarian since 2006, says. Two years ago, a childhood friend of his called Sanjo, disabled in infancy by the viral infection and reliant on crutches for mobility throughout his life, passed away. “I won’t say polio killed him, no. But did polio limit his potential to living a full life? The answer is yes,” he says. “I said to myself, is there something I can do, to make sure another child doesn’t go through this pain? I was going to do this ride, and I said, okay, I’m going to use to it to draw so much attention to polio, okay? And also to raise funds to support the immunisation drive.”

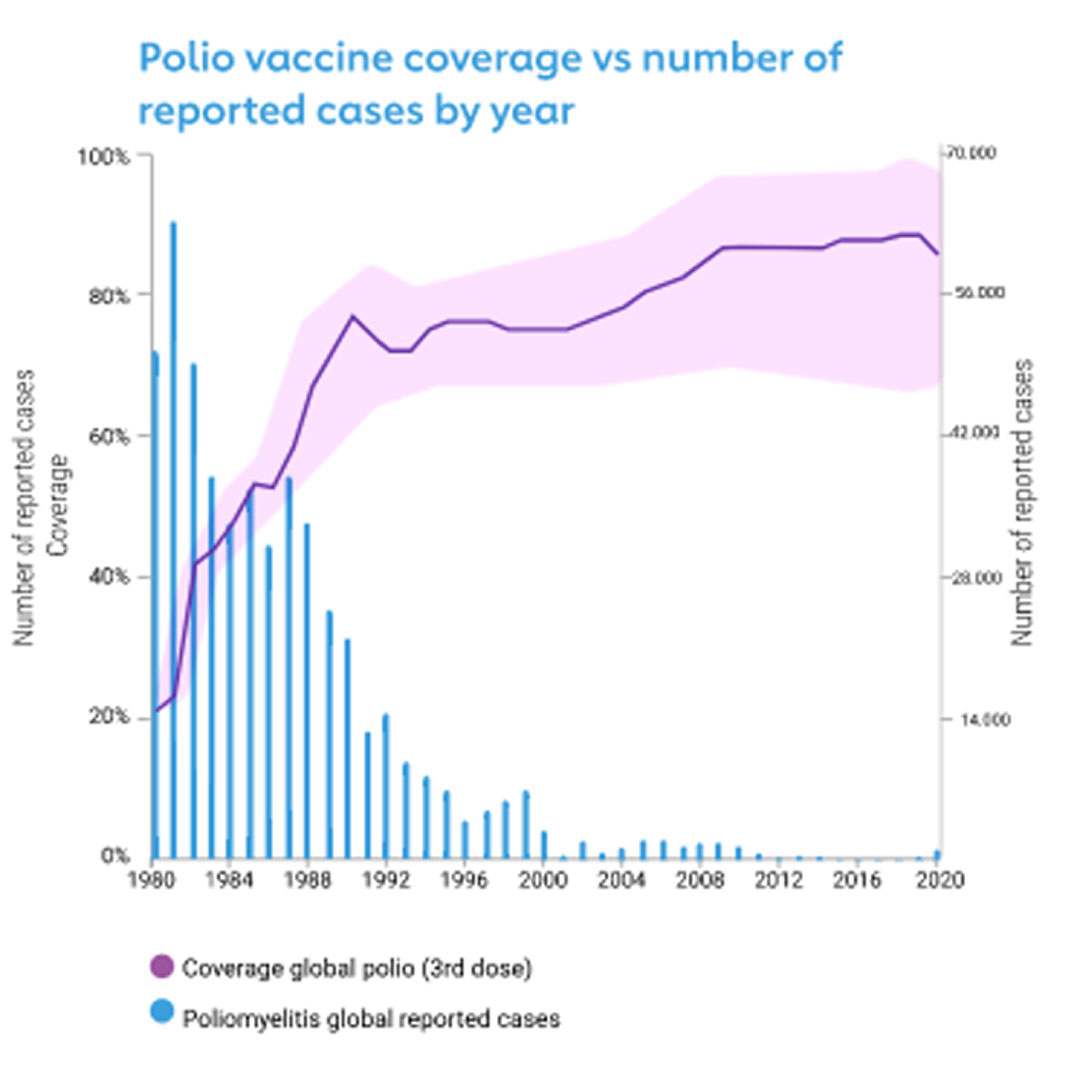

In 2022, that’s a more pressing objective than previous generations of polio campaigners might have hoped. Since the vaccine’s invention in 1952, and especially since the establishment of the Global Polio Eradication Initiative in 1988, the fall-off in global cases has been extraordinary. Graph polio cases in any region of the world across the last four decades or so and you’re looking at cliff-edge tumble; worldwide, cases are down 99%. In most places, the line levels out at an annual incidence of zero.

In 2020, Nigeria became the last African country to be declared free of wild polio. It was a major achievement: for decades, Nigeria’s polio sufferers had represented a major portion of the global polio toll. Today, the virus remains endemic only to Pakistan and Afghanistan.

Have you read?

But since 2020, amid the health system disruptions of the COVID-19 pandemic, the fragility of the world’s gains against polio has become alarmingly clear. In October 2021, an outbreak of polio surfaced in Ukraine. In February 2022, a case of wild poliovirus in Malawi raised a red flag; in March, circulating vaccine-derived polio was detected in Israel. Meantime, Pakistan recorded more polio cases in the first quarter of 2022 than it detected in the entire preceding year. More recently still, evidence from sewage samples in London suggests the virus’s presence in the UK.

For Adeyanju, acolyte of forward momentum, the possibility that the pace of the campaign risks faltering at this vital juncture is clearly maddening. “We have the technology. We have the vaccine to cure this – to stop the virus,” he says. “We have this sign in Rotary,” he says, lifting his pinched forefinger and thumb towards his webcam in demonstration. “We’re this close. We’re this close to eradicating the virus.”

On May 29 – 41 days, 12,000 kilometres, 13 countries, and, by his own count, four fleeting glimpses of death since leaving London – Adeyanju made it to Lagos, and was greeted by a jubilant, thronging crowd.

That same day in Geneva, global public health leaders gathered to talk about polio at a session of the World Health Assembly. Here, the tone was determined, but certainly less triumphant than at the victory parade in Lagos. The “worrying developments” of recent months were “expected” in the final stages of an eradication effort, said Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, WHO Director-General. But, the experts cautioned, urgent action was required before a “unique” window of opportunity closed forever.

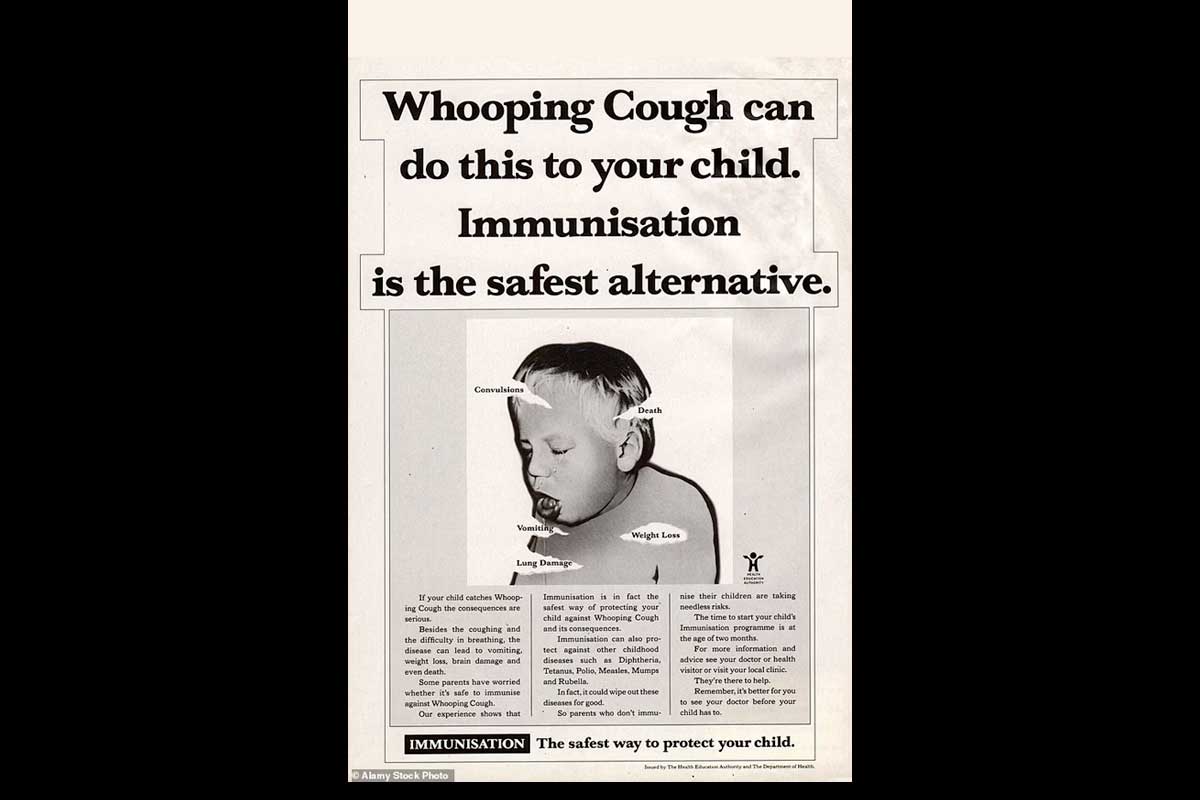

A paradoxical challenge for an end-stage eradication campaign like this one is that the disease becomes, in many places, vanishingly rare. Parents forget what infection can cost their child. Vaccination can begin to seem less crucial.

Growing up with Sanjo inoculated Adeyanjo against that false sense of security. Statistically, one in 200 polio infections leads to the kind of irreversible paralysis that Sanjo suffered in both of his legs. In the unluckiest 5-10% of patients, the muscles that freeze are respiratory muscles, leading often to death, or else to an artificial respirator.

To Adeyanjo, Sanjo’s preventable disability was tragedy enough. “When we go do all those things that kids normally do – go swimming, jumping, playing football – my friend couldn’t join us. And not because he didn’t want to, but because he was limited by polio.” Walking was a struggle for him all his life, Adeyanjo says. “I know he suffered a lot.”

Kunle Adeyanju

|

“The world is like a big giant book. The more you visit places, the more pages in the book you open, the more exposed you get. And it humbles you.” |

Eagle

|

Model: Honda CB500X “It’s a machine, but I think it’s a machine with a soul.” |

Adeyanjo, crosser of continents, climber of mountains, unsurprisingly projects a restless, hungry kind of energy. “I find it difficult to stay in one place,” he says. Lockdown was “extremely hard. I think I would use the word ‘torture.’” When the movement bans were announced, he decamped to the countryside so that he could run 14 kilometres each morning and each evening without breaking isolation. After that period of confinement, pounding the same stretch of road day after day, the London to Lagos ride represented liberation.

With Sanjo and the lockdown on his mind, those 750-kilometre days on the road, singeing his tires on desert tracks or negotiating precipitous passes in the Atlas Mountains, felt particularly poignant. “It’s all about movement, you know? It’s all about the opportunity, the grace, that my body can carry me on a bike to do this thing,” he says. “This beautiful world – coming into this world and not exploring it, I think it’s a waste.”

Some of that grace – or at least its insurance policy – comes bottled in vaccine vials. “I’m able to move like this because my body can carry me. Because I didn’t get polio,” says Adeyanju.