One year ago, I was walking through Redemption Hospital outside Monrovia, Liberia, and I remember thinking to myself, this is pretty bleak.

As we were touring the dim, tiny space, we turned a corner and saw a boy, badly burned and injured, sitting out in open air on a folding table, waiting listlessly for medical attention. The facility was crowded, but not in a bustling way that typifies many health facilities in sub-Saharan Africa.

Instead, you felt worried that many who came to Redemption — despite its name — might not be able to receive the care and salvation they needed. The staff was doing heroic and creative work with what they had, but they noted that they frequently faced a shortage of even the most basic supplies.

On that visit, Liberians proudly spoke of how far they had come since the civil war that devastated their country a decade ago. It was clear that real, incremental progress was happening there — sometimes despite all odds to the contrary.

But relative to so many other clinics, hospitals, and health facilities I had visited across the continent over the years, the situation in Liberia, as illustrated by this specific site visit, felt unfinished and fragile. So while like most people I have been stunned at the severity of this Ebola crisis, I can’t say that I was surprised to see that Ebola was taking hold and spreading in a place like Liberia, and devastating facilities like Redemption.

Contrast that with my experiences one year later. For the last two weeks, I’ve been in Rwanda, primarily interested in learning more about how its health care system continues to evolve and improve.

It was my third trip to the country, having visited previously in 2007 and 2011, giving me the chance to compare its progress against itself and against its peers. As I was packing for the trip, I was asked repeatedly by well-intentioned friends and family, “Aren’t you worried about getting Ebola?”

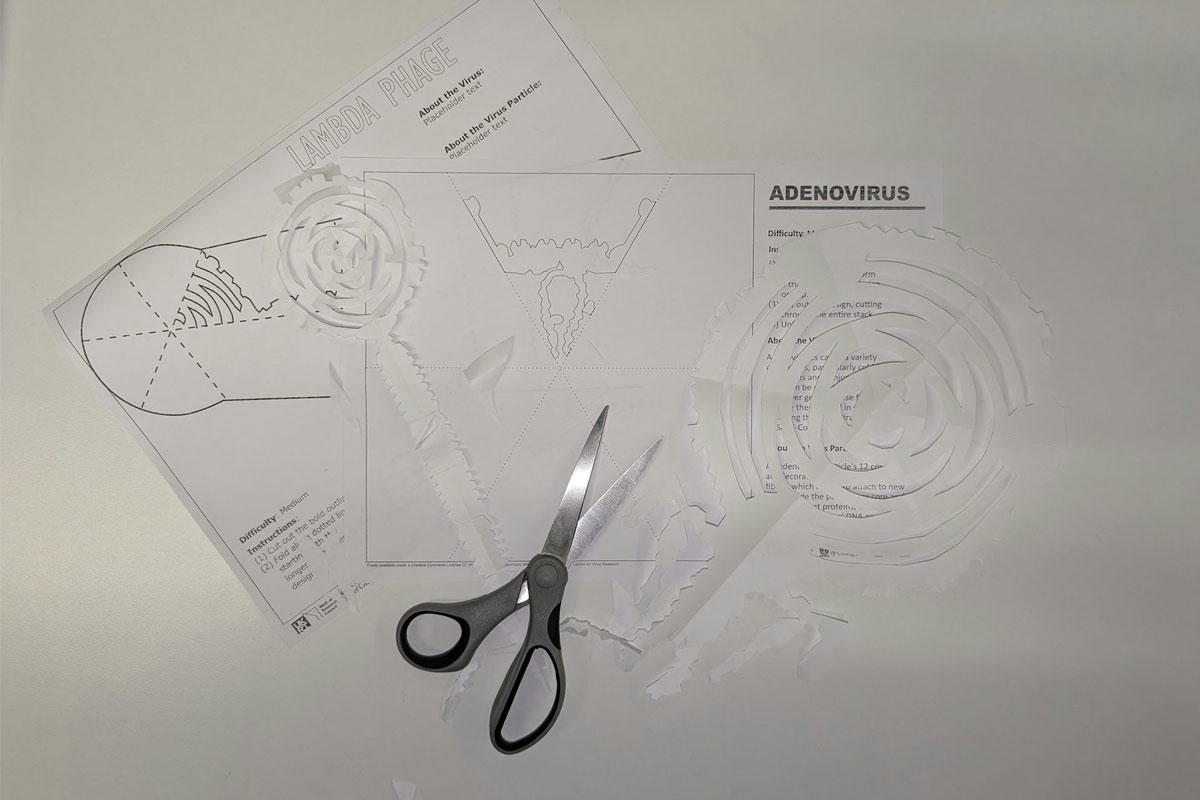

An Ebola kit sits unused (but at the ready) in a Rwandan health center pharmacy, next to a stocked supply of antiretroviral drugs, oral rehydration salts, malaria treatments, and other medicines.

Given what I knew about how the disease spread, and with only one case to date approaching Rwanda’s borders in neighboring Democratic Republic of Congo, I was able to answer them with a fairly confident “no.”

But after two weeks in the country, I realized I had so many more reasons to say “no.” Of course, I’m still not bold enough today to predict that Ebola will never arrive in Rwanda, given the urgency of the crisis and models of exponential spread that merit real concern. But I had a greater understanding of why Rwanda was not Liberia, and why the health system there was better able to weather new (and old) threats.

Here are 4 reasons why

1. Health care workers

One of the clearest lessons of the West African Ebola epidemic so far has been how dangerous it is to have weak health systems and insufficient human resources for health.

Rwanda, they not only have recruited, trained, and retained a vast army of volunteer health care workers (HCWs) — three for every single village across the country — but they have also built up a referral process around them

These HCWs are the lynchpins of the system, ensuring that Rwandans with common and more easily treatable illnesses (such as fever, diarrhea, and malaria) can receive care at the local level without overburdening higher levels of the health system.

That, in turn, frees up nurses and doctors to work in health centers, clinics, and hospitals and to have the time and space to treat more severe or specialized cases. We visited each level of the system in our time on the ground, and it was clear at each stop that health staff knew their roles, knew when to refer patients, and had the tools available to deliver effective care

2. Political prioritization

We heard frequently in our site visits that health care for Rwandans was a top political priority, from President Kagame on down through the government’s chain of command. This was not news to me, as I had heard Rwanda’s dynamic Minister of Health, Dr. Agnes Binagwaho, speak at many international meetings over the years and even engage citizens in a Q&A via #MinisterMondays on Twitter.

She was always the first to unabashedly point out how Rwandans knew what was best for Rwandans’ health and how focused she was on achieving outcomes for her people.

Critically, this was not just political grandstanding — it had translated into real dollars (or Rwandan francs, to be specific) and real outcomes for health in the country. Rwanda is one of just six African countries to have met its 2001 Abuja commitment to spend at least 15% of its budget on health; in fact, Rwanda regularly exceeds this target, averaging 22% each year since 2006. And unlike many of its peers, Rwanda is on track to achieve many of the Millennium Development Goals, including MDGs 4 and 6, focused on child health and HIV/AIDS, respectively.

3. Money

In addition to a growing pot of domestic resources for health, Rwanda has been the definition of a health “donor darling” over the last decade, receiving what some might argue disproportionately high levels of foreign assistance from key donors and programs relative to its size and disease burden. At nearly every health facility across the country, you see staff supported by and commodities purchased by donors including the Global Fund, PEPFAR, PMI, GAVI and various other bilateral initiatives.

By some estimates, external resources make up anywhere from one-third to nearly half of Rwanda’s health budget. But these resources appear to have had an additive effect on overall health spending and programming. By allowing donor resources to support key programs to fight diseases like AIDS and malaria, the Rwandan government has been able to spend its own health resources on broader systems strengthening, preventative health campaigns, and innovations that put it ahead of the curve.

Anecdotally, one Rwandan hospital we visited had one of the more sophisticated neonatal units I had ever seen in the region; fingerprint scanning technology for staff to enter specific buildings; and a full range of vaccines, including more expensive options such as HPV, for all its children.

Dr. Alfred, the lead physician at Nyamata District Hospital, shows off the fingerprint-recognition technology at the entrance to one wing of the facility. Credit: Erin Hohlfelder

4. Trust

Despite concerns about the Rwandan government’s political proclivities (I’ll leave that discussion to others for the time being), but when it comes to health, it is hard to argue that the government is not delivering results for its people.

In turn, the overwhelming majority of citizens with whom we met expressed that they trusted their government to provide health care and felt like they were seeing improvements in their day-to-day lives.

Contrast that with the situation across West Africa at the moment, where trust between the governments’ officials and their people has faltered.

We’ve seen citizens turned away from overly full health facilities, myths about Ebola continue to flourish despite formal information channels, a mistrust of health care workers, and even violence towards those who aim to provide care.

At the end of the day, if citizens don’t trust that showing up to a health facility will lead to care and improved health, they are more likely to stay home and perpetuate the spread, rather than containment, of diseases.

Of course, none of this is to say that Rwanda’s system is perfect or that the Liberian health care experience should or even could look like Rwanda’s.

And indeed, ten years of Liberian civil war a decade ago took a dramatically different physical, economic, psychological, and political toll on the country than did the (equally horrific, but very different) Rwandan genocide 20 years ago, which also has implications for how the country rebuilt and how citizens respond.

Approximately 100 Ebola patients were moved from nearby Redemption Hospital in Liberia to the Ebola Treatment Unit Island Clinic. Credit: Morgana Wingard/ USAID.

But surely, if we hope to rebuild Liberia and other affected West African countries when the Ebola crisis is eventually contained — an effort that will likely take years, not months — we can benefit from borrowing some of the lessons highlighted in the Rwandan experience.

In doing so, we can restore places like Redemption Hospital and ensure that, once again, they are seen as places where people come to be saved.

This post originally appeared on Medium.