Beating back the Aedes aegypti mosquito

Scientists are taking a multipronged approach to tackle this dangerous carrier of dengue, yellow fever and other noxious viruses.

- 13 January 2026

- 12 min read

- by Knowable magazine

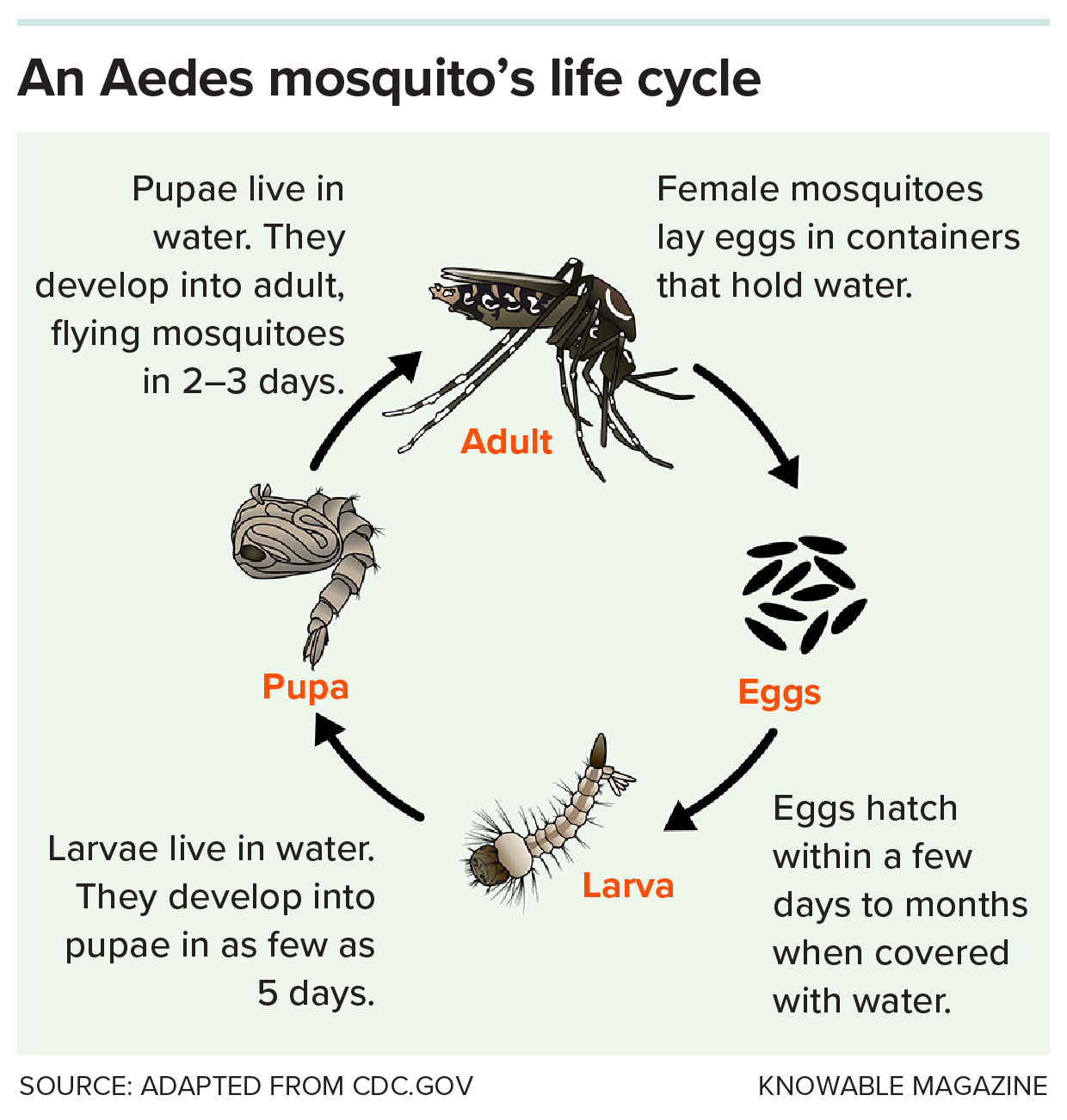

Deep in northwestern Africa, a high-pitched hum pierces the moist forest. It is the mosquito Aedes aegypti, laying its eggs inside water-filled tree holes and feeding on various animals, posing little danger to any person it encounters.

But that is a scene from the distant past. Everything changed about 5,000 years ago, scientists reckon, when the African climate shifted, and this area — the Sahel — like the Sahara region farther north, became a drier place. Even A. aegypti, whose eggs can dry out and survive for months, couldn’t tolerate nine months of hot, dry weather every year.

What happened next turned the mosquito into a scourge.

Luckily for the insects, people — who up until then had lived nomadic lifestyles — began to settle down and to domesticate crops. They used clay pots to store and transport water — unwittingly providing a year-round, reliable habitat for eggs and juvenile mosquitoes. It meant mosquitoes could continue to exist in this region, as long as they stuck around humans.

In fact, being around people proved so beneficial to Aedes aegypti’s survival, scientists believe, that its antennae evolved to react more strongly to human odors than to those of other animals.

A preference for biting humans helped to ensure that, after a female mosquito consumed human blood and was ready to lay her eggs, there would always be a manmade source of water nearby, says Princeton evolutionary biologist Carolyn McBride. And so Aedes aegypti followed people and their containers everywhere — out of Africa, hitching rides in the water-storing vessels on early slave ships; around the world, through global trade; in used car tires, which fill easily with water. “It loves breeding in old tires,” says McBride.

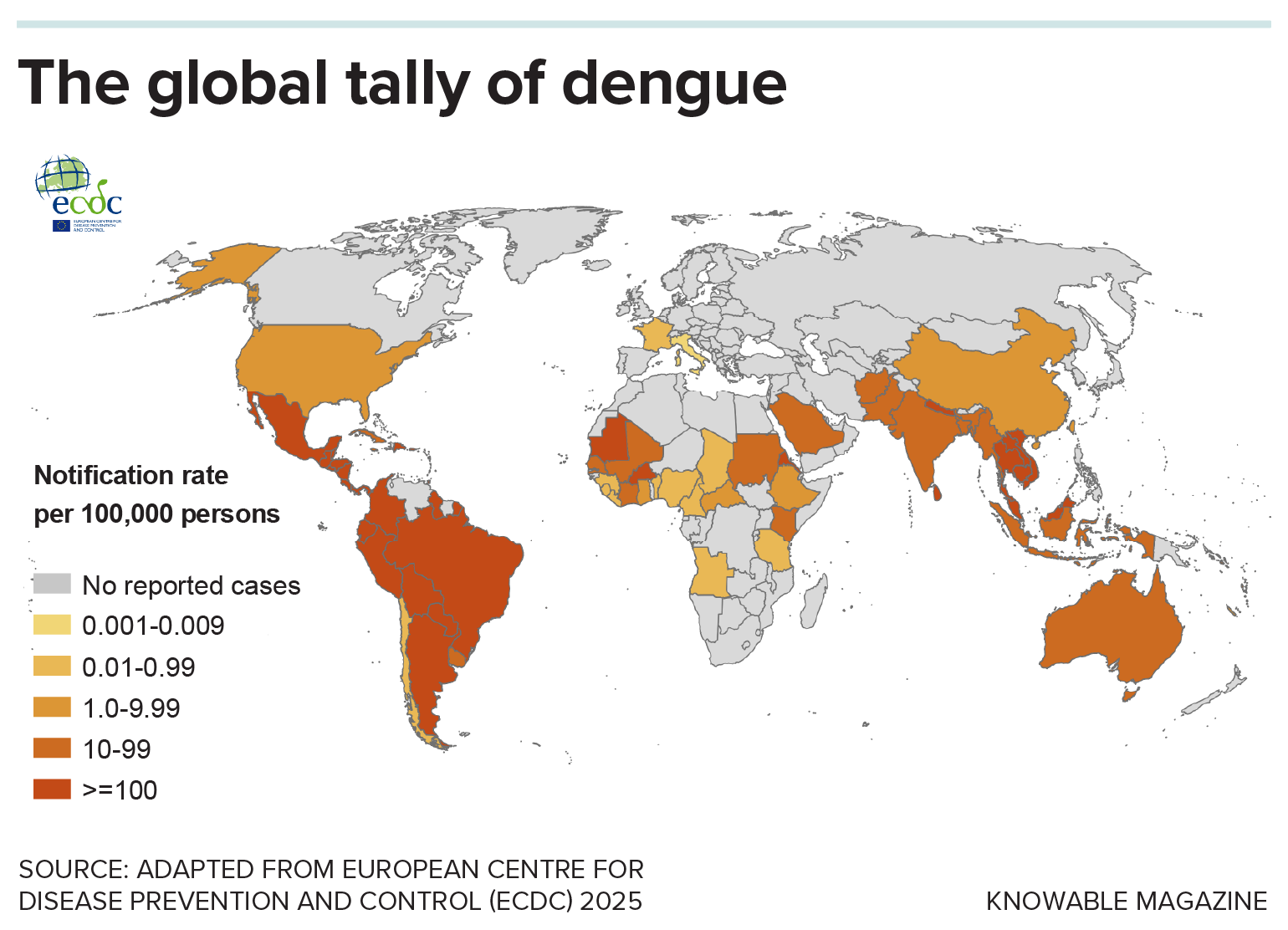

The prolific rise of Aedes aegypti — and to some degree its less human-specialized cousin, Aedes albopictus — has allowed tropical diseases like dengue to spread globally. The dengue virus, and others like chikungunya, Zika and yellow fever, kill tens of thousands of people in tropical countries every year. The ramifications for human health became clearer than ever in 2024, which saw the world’s deadliest dengue season unfold, especially in South and Central America and Southeast Asia, with more than 14 million global cases and over 12,000 dengue-related deaths worldwide.

Experts worry that the trend could worsen as international travel, trade, urbanization and climate change continue to pull the insects into new areas, including Europe and the United States. One 2024 study estimated that, for each additional degree Celsius the planet warms, dengue cases in parts of Africa could increase by 10.5 percent.

That’s why scientists have been busy developing and testing new methods, from new vaccines to insect-infecting bacteria, for combating Aedes aegypti and the diseases it carries. “Having this mix of tools that we know work is a situation we’ve not been in before, and gives us hope that we can reverse or at least limit some of these potential future increases,” says Oliver Brady, an epidemiologist at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine who studies the spread of mosquito-transmitted viruses.

Have you read?

The ‘perfect mosquito’

Aedes aegypti is the “perfect mosquito” to spread disease, says mosquito expert Cameron Webb of New South Wales Health Pathology, an Australian forensics and diagnostics provider. While most mosquitoes take only one big blood meal to start making eggs, Aedes aegypti often enjoys multiple courses from different people. And, for reasons that scientists are still trying to understand, Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus are much more prone than other mosquito species to getting infected by viruses like dengue and chikungunya, which then stick around and multiply in the insects’ bodies. After a mosquito is infected, “it will remain infected for the rest of its life,” passing on viruses to new people with every bite, says virologist Louis Lambrechts of France’s Pasteur Institute.

Dengue and chikungunya (which can be misdiagnosed as dengue) are actually relatively easy to treat, says André Ribas Freitas, a physician and researcher at the São Leopoldo Mandic university campus in Campinas, Brazil. Most people survive the mild symptoms such as headaches, fever, muscle pain and skin rashes. When people die of dengue, it’s usually because of an extreme drop in blood pressure that happens when blood vessels become leaky, or because the infection spreads to the heart, brain and liver. These complications require careful administration of fluids and intensive care and life support. But in places like Brazil, for instance, which saw roughly 6,000 deaths in 2024, many densely populated areas don’t have enough health care facilities and experienced doctors, and emergency rooms in large cities like Campinas became overwhelmed, Freitas says. “It’s too many patients, and the treatment needs good and attentive care.”

CREDIT: ZUBAIR MUNA / SHUTTERSTOCK

Curiously, the most severe dengue infections often happen upon people’s second encounter with the virus. Scientists believe this is because dengue is not one virus but actually four different subtypes. Each one looks very different to our immune system — so different that suffering an infection with one type doesn’t necessarily protect against another. But the immune system’s reaction to the virus can actually make the second infection worse. With a first-time dengue infection, “you don’t even see the symptoms. But the secondary one, it can become lethal,” says Navin Khanna, a dengue researcher based in New Delhi at the International Centre for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology.

To many experts, the rise in cases underscores that traditional methods of preventing disease outbreaks aren’t sufficient. Window screens can impede airflow and are expensive; repellents aren’t affordable to most people; mosquito nets don’t work against day-biting Aedes mosquitoes, unlike night-biting Anopheles mosquitoes that transmit malaria. Many governments send officials into towns and cities to go door-to-door to manage water-holding containers or apply larva-killing substances, such as the chemical temephos, or to fumigate with insect-killing chemicals like pyrethroids during disease outbreaks.

But mosquitoes have evolved resistance to some insecticides, says Amy Morrison, a dengue and Aedes expert at the University of California, Davis, who is based in Iquitos, Peru. There, as in many other places including Brazil and Colombia, temephos and pyrethroids are “off the table now,” she says. And not all communities and individual houses are visited or treated regularly enough to put a dent in mosquito populations. In Iquitos, for instance, effective insecticide treatment would mean visiting more than 90,000 households, spraying for over two minutes in each household, on three occasions one week apart. “Some governments don’t have resources to do much of anything,” Morrison says.

Morrison has found promising results for new methods that have a longer-lasting mosquito-killing effect — such as targeted indoor residual sprays, which put long-lasting insecticides in places where mosquitoes rest, and repellents released into the indoor air to deter mosquitoes. But the challenge is regular and strategic implementation, she says. “It’s an endless battle.”

The problem gets stickier when looking beyond households. Aedes aegypti can lay eggs in anything from empty coffee cups and tuna cans to drains and rainwater tanks. And each female lays its eggs in multiple places in order to maximize the chances of the eggs hatching. Reducing breeding opportunities for mosquitoes requires infrastructure solutions — improved waste disposal systems, regular treatment of standing water with insecticides, or strategies to populate pools with larva-gobbling fish. But even in wealthy countries, “it comes with a price tag that is sometimes difficult to manage,” Webb says.

CREDIT: ISTOCK.COM / LUIZSOUZARJ

A vaccine conundrum

Where traditional control methods are lacking or ineffective, Freitas sees hope in vaccines against Aedes-borne diseases. These are typically based on weakened or modified viruses or virus-like particles that trigger the body’s immune system to generate antibodies that stick to certain proteins on the virus’s surface, stopping it in its tracks.

The approach proved effective back in the 1930s in developing a vaccine against yellow fever that has been saving lives ever since. A 2021 study estimated that, between 2005 and 2018, mass vaccination campaigns decreased the number of yellow fever outbreaks in 11 African countries by 34 percent. Research recently also delivered two vaccines for chikungunya, the first of which has been administered to tens of thousands of people globally.

There is still no vaccine for Zika — following a burst of infections roughly 10 years ago that caused thousands of birth defects in babies when their mothers contracted it during pregnancy, the virus has become too rare for the large-scale trials required to assess safety and efficacy of a vaccine, says Annelies Wilder-Smith, an infectious disease expert at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

But the greatest challenge, experts agree, is making a vaccine for dengue. “A dengue vaccine is clearly not for the faint of heart,” says Wilder-Smith.

That became apparent when the pharmaceutical company Sanofi, after 20 years of development, trialed the vaccine Dengvaxia in more than 35,000 children in Southeast Asia and Latin America. While the vaccine initially showed promise in protecting many of them against dengue, according to those trials, scientists also reported an alarming observation: In children between 2 and 16 years of age who had never had a dengue infection, receiving the vaccine later led to more severe dengue infections and a higher likelihood of hospitalization than was seen in unvaccinated children.

Scientists believe this happened because the vaccine effectively acted like a first-time infection with dengue — making the second, actual, infection worse. The severity of second-time dengue infections likely has to do with the fact that the various dengue subtypes have different proteins studded on their surfaces. Because of this, antibodies against one dengue subtype don’t effectively block the ability of the other subtypes to enter human cells. But many of the antibodies still end up sticking in places on the virus, forming large tangles of molecules that, along with the virus itself, are taken up by immune cells. The viruses then act like Trojan horses, killing these immune cells and reproducing, spreading and wreaking havoc, Khanna says.

In 2022 a second vaccine, Qdenga, was introduced. It showed fewer safety issues, but it doesn’t fully protect people against all dengue subtypes and is less effective in people who haven’t contracted dengue before getting vaccinated, Wilder-Smith says. A third vaccine, still being tested, also doesn’t seem to provide full protection, she adds. Like Dengvaxia and Qdenga, it may prove useful in people who previously have been infected with dengue, she says. “In the absence of a perfect vaccine, you use what you have.”

Researchers are finding clues on how to build more effective vaccines. Khanna, for instance, recently reported promising results in mice when testing a vaccine that is designed to elicit only virus-blocking antibodies for each dengue subtype without triggering those troublesome virus-helping ones — an approach that, in principle, would protect everyone against all dengue subtypes. “That would be a game changer,” Morrison says.

Bacteria versus mosquitoes

Scientists are also working on ways to take aim at the mosquitoes themselves, by harnessing bacteria called Wolbachia that inhabit the bodies of many insect species. Many such bacteria have the curious effect of killing their host’s offspring should males hosting Wolbachia mate with Wolbachia-lacking females. Scientists recently worked out why this happens: The male’s sperm becomes loaded with toxins made by Wolbachia, and these kill the resulting embryos unless the females also carry Wolbachia, along with the toxin’s antidote.

As early as the 1960s, scientists began to wonder: If they could get Wolbachia to infect mosquitoes, might the bacteria act as a kind of natural insecticide? Fast forward a few decades, and several companies are now raising Wolbachia-infected males by the millions; in the wild, these mate with uninfected females, killing the resulting offspring and suppressing local mosquito populations.

The trouble with this approach, though, is that mosquito populations quickly bounce back when the infected males die out, meaning that scientists need to keep releasing new ones. While that’s a sustainable business model in regions with enough resources to pay for continuous releases — like parts of the United States and countries like Singapore — it’s less feasible for the lower- and middle-income countries that are hardest hit by dengue, says evolutionary biologist Michael Turelli of UC Davis.

But scientists have discovered other ways of wielding Wolbachia to their advantage. In the early 2000s, researchers in the United Kingdom discovered in fruit flies that a certain strain of Wolbachia called wMel seems to make the insects resistant to particular viruses. Turelli suspects that, inside insect cells, wMel competes for the same resources, like protein-building molecules, that viruses also need to thrive. And because wMel is much better at acquiring these resources than the viruses are, it hampers the ability of the viruses to multiply. When scientists infected Aedes aegypti with wMel, this seemed to make the dengue virus less likely to reach the insects’ salivary glands. The result: “They’re going to bite you, but they’re not going to give you a horrible disease,” Turelli says.

The not-for-profit World Mosquito Program has built on this idea, releasing wMel-infected males and females into the wild. The infected females reliably spread wMel Wolbachia to their offspring, making them unable to transmit disease. Meanwhile, when infected males mate with wild, Wolbachia-less females, their offspring die, helping to ensure that only Wolbachia-infected young survive.

CREDIT: WORLD MOSQUITO PROGRAM

The program has tested the mosquitoes in 15 countries — including Brazil, Indonesia, Colombia, and Kiribati — with the buy-in of communities where they’re released, says Nelson Grisales, a medical entomologist with the program. This has already put a dent in disease transmission, for instance in Yogyakarta, Indonesia, where scientists counted 86 percent fewer dengue hospitalizations in areas with Wolbachia-carrying mosquitoes compared to Wolbachia-free areas. And in contrast to vaccines, which may not be accessible or affordable to everyone, Wolbachia “will protect anyone who is in the territory,” Grisales says.

To ramp up the effort, the World Mosquito Program recently partnered with the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation, a Brazilian scientific institution, and Brazil’s Institute of Molecular Biology of Paraná to build Wolbito do Brasil, the world’s largest mosquito breeding facility, in the city of Curitiba. In a statement, the facility’s chief executive said it has the capability of churning out 100 million wMel-infected mosquito eggs every week.

But the Wolbachia strategy may not work everywhere. For one, it seems to be less effective in places that see long periods of temperatures over 104 degrees Fahrenheit, due to reduced Wolbachia survival. And even where Wolbachia can be reliably introduced, the mosquito populations will require long-term monitoring — and potentially additional releases — to ensure that they’re effective. One long-term concern is that the viruses could evolve ways of outsmarting their Wolbachia neighbors, Turelli says.

There are other biological strategies that scientists are working on, including genetically engineering Aedes aegypti mosquitoes so that their female offspring are unable to fly, or so that offspring are only male — and, ultimately, quashing mosquito populations.

Indeed, experts agree it’s only through a combination of tools that Aedes aegypti -borne diseases can be suppressed. These methods will prove increasingly important as the viruses continue to spread, and if new ones spill over into human populations; Zika, chikungunya, dengue and yellow fever are thought to have originated in African forests, where many such viruses circulate among wild animal populations. Just as it was people who spread Aedes aegypti around the world, so it is human actions — new technologies, smart planning and good foresight — that can make the buzzing, biting and spreading insects less dangerous for everyone.