Eating less food from animal sources is key to reducing the risk of wildlife-origin diseases and global warming

Infectious diseases originating in wild animals are high and may be increasing. This is a sign that ecosystem degradation is undermining the planet’s capacity to sustain human wellbeing.

- 29 August 2022

- 6 min read

- by The Conversation

The world is at greater risk of infectious diseases that originate in wildlife because people are encroaching on tropical areas of wilderness to feed livestock and hunt wild animals.

Tropical deforestation and over-hunting are also at the root of global warming and mass species extinction.

Devastating pandemics like HIV/AIDS, Ebola and COVID-19 are likely to have originated in wildlife. This serves as a reminder of how human impacts on the environment interlink with disease as well as with climate change and biodiversity loss.

Food, then, is one key to solving a lot of problems.

We recently conducted a thorough review of the scientific literature to explore whether outbreaks of infectious diseases originating in wildlife could be linked to ecosystem degradation caused by the global food system.

The review revealed two ways to tackle the interrelated crises of wildlife-origin diseases, global warming and mass species extinction. The first is a global transition to more plant-based diets, so as to limit agricultural encroachment on tropical wildlands. The second is to curb demand for wild meat in tropical cities.

Eating less food from livestock sources

Closer to the Equator, biodiversity becomes richer. These tropical regions have historically seen less development and are particularly rich in wildlife and carbon stocks. But in recent decades agricultural frontiers have expanded rapidly into tropical forests.

The expansion of farmland into tropical forests may be increasing contact between wildlife, people and livestock. This in turn may enhance the likelihood of pathogens jumping from one to the other.

Such habitat destruction also has a negative impact on large herbivores and predators, as they lose sources of food and breeding grounds. This can lead to an increase in “generalist” species of rodents, bats, birds and primates that are better adapted to human-modified landscapes. Some of these species are known “reservoirs” for infectious diseases of livestock and humans. Intensive livestock farms further increase the likelihood that domesticated animals become intermediate hosts for wildlife-origin diseases, often amplifying the risk of human contagion.

In addition, if the global human population continues to grow and adopt diets rich in livestock source foods, it’s unlikely that global warming can be kept well below 2°C. It’s also unlikely that the rate of species extinction can be slowed. This is because livestock production has the highest environmental footprint of all foods in terms of land and water use, greenhouse gas emissions and pollution of terrestrial and aquatic systems.

It’s not realistic or even desirable to expect everyone to become a vegan (following a completely plant-based diet). But flexitarian diets could feed the growing world population without further expanding farmland into tropical wildlands, and with reductions in greenhouse gas emissions. These diets consist of large amounts of plant-based foods (including vegetable proteins like pulses, nuts and seeds), modest amounts of fish, poultry, eggs and dairy and small quantities of red and processed meat.

Together with conversion to environmentally friendly or organic farming and cutbacks in food losses and wastage, diets low in livestock source foods are then a key component of a sustainable global food system. They have other health benefits too, such as reducing obesity, diabetes, heart disease and colorectal cancer.

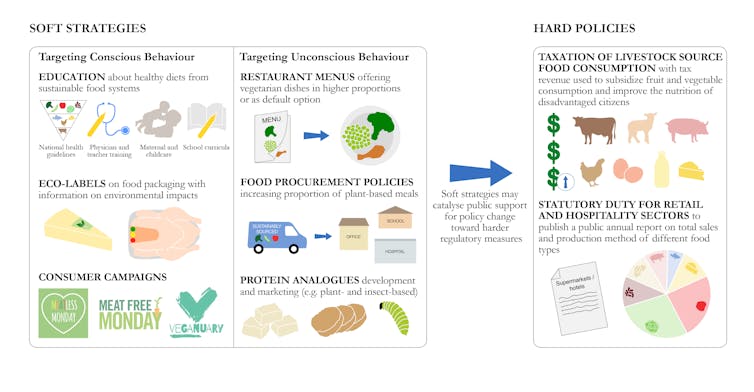

Measures available to governments, civil society and businesses to promote a reduction in the global consumption of livestock source foods are illustrated in the figure below.

Governments tend to dodge such interventions for fear of public backlash. But the public expects government leadership in tackling such a complex challenge.

Curbing wild meat demand in tropical cities

In the tropical forests of Africa, Asia and South America, over the past 30 years hunting pressure to supply nearby cities has radically increased. High levels of wild meat trade may enhance the risk of disease transmission from wildlife to humans, because it’s hard for governments to enforce biosecurity measures on hunting grounds and at abattoirs, food markets and restaurants.

Without effective law enforcement and sustained consumer campaigns to reduce urban demand, bans may fail to discourage trade. In fact, consumers’ strong preferences for wild meat mean that they may continue to purchase it despite price increases induced by a ban. This would boost black markets.

In urban areas, legume, fish and livestock source proteins are easily available at affordable prices. But some indigenous people and rural communities rely on hunted meat for a vital part of their nutrition and income. Outright bans would undermine their rights to hunt sustainably within their territories.

Bans could also shift wild meat trade to illegal, unregulated channels where less attention is paid to biosecurity measures necessary to prevent contagion from wildlife-borne diseases.

The ideal is then to contain tropical wild meat hunting and trade by curbing demand in urban areas while supporting hunting rights and biosecurity measures among communities in remote subsistence areas.

Avoiding biohazards from animal source foods

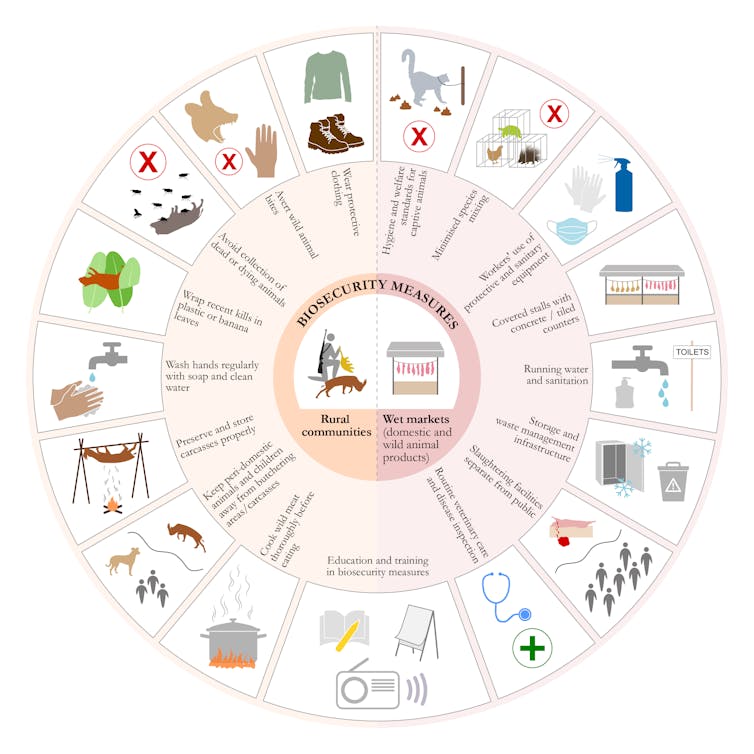

Interventions in rural communities should provide wild meat hunters, traders and butchers with training in inexpensive biosecurity measures they can easily adopt to avoid infection from contact with wild animals. Biosecurity measures should also be extended to livestock and wildlife farms, abattoirs, food markets and restaurants, as illustrated in the figure below.

Other physical distancing measures should also be taken on farms, pastures and live animal markets. These include fencing and reducing livestock densities to minimise contact with wild herbivores, planting fruit trees visited by bats at a distance from livestock sites, and limiting the number of animals on sale in live animal markets.

Different strategies across different regions

People in different regions rely on animals for food to different degrees. Efforts to reduce livestock production should focus on curbing excessive consumption in wealthier countries and the expanding metropoles of developing countries.

In the poorer rural areas of developing countries, home gardening and smallholder livestock development programmes can help decrease malnutrition, but with less environmental impact.

People who live where it’s hard to grow crops – such as pastoralists in arid rangelands and hunter-gatherers in tropical rainforests and the Arctic – will instead continue to rely conspicuously on animals for nutrition. Nonetheless, the low environmental impacts of their subsistence way of living are not comparable to those of dense and better off urban populations.

Change is urgent

The incidence of infectious diseases originating in wild animals is high and may be increasing. This may be yet another sign of the way in which the degradation of ecosystems is undermining the capacity of the planet to sustain human health and wellbeing.

Dietary shifts away from livestock source foods and wild meat are crucial to protect the environment, safeguard poorer communities and reduce the risk of disease outbreaks and pandemics.![]()

Authors

Giulia Wegner, Researcher, Sustainable Development and Wildlife Conservation, University of Oxford

Kris Murray, Associate Professor, Environment and Health (MRCG@LSHTM); Senior Lecturer (Ecological Health, Imperial College London), London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Disclosure statement

Giulia Wegner carried out part of the preparatory research for this review study while supported by a doctoral studentship awarded by the Recanati Kaplan Foundation.

Dr Kris Murray receives funding from the Medical Research Council UK, The Wellcome Trust and the UK Global Challenges Research Fund. He currently serves as a scientific advisor/board member to the Soulsby Foundation and The Regenerative Society Foundation.

Partners

University of Oxford provides funding as a member of The Conversation UK.