The future with COVID-19: three potential scenarios

What our lives will look in the short to medium term future is uncertain, but what does seem clear is we won’t return to a pre-COVID-19 life any time soon. Here are three potential scenarios that infectious disease experts have sketched out for how the pandemic might evolve.

- 18 May 2020

- 4 min read

- by Priya Joi

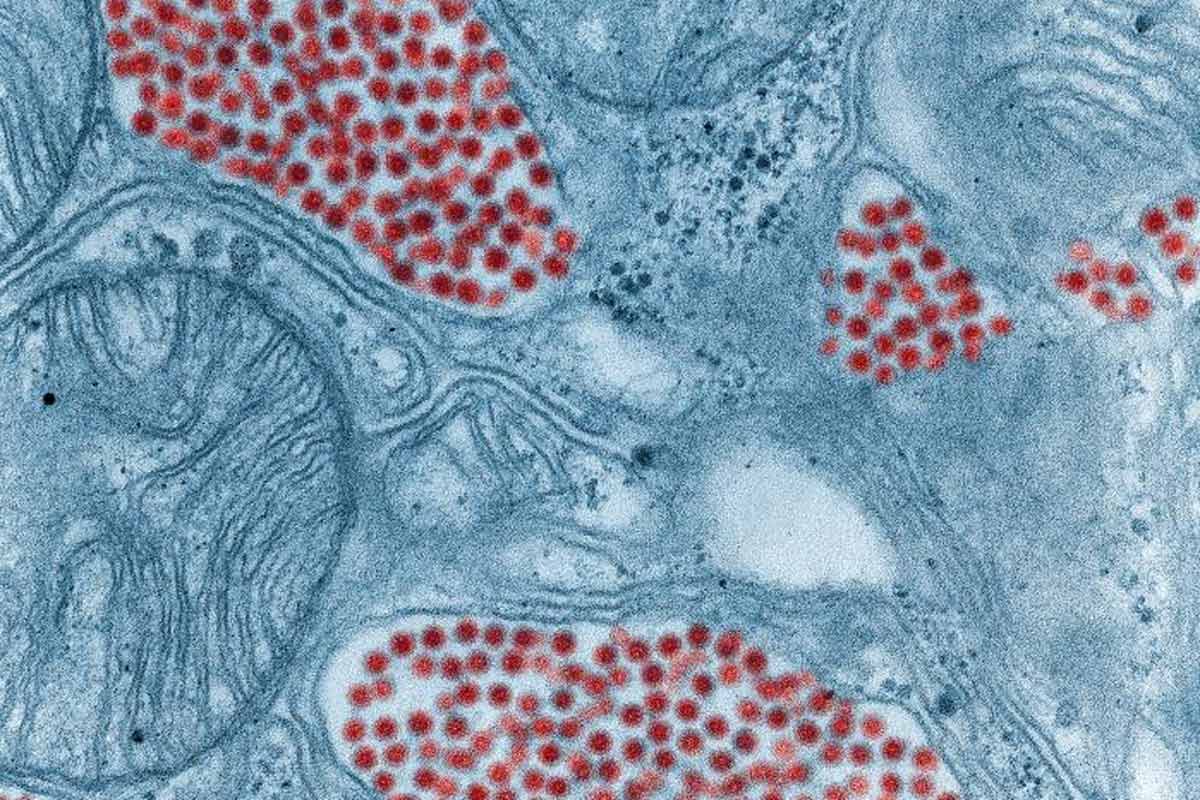

Most countries, even high-income ones, were spectacularly unprepared for the COVID-19 pandemic that has dominated our daily routines in 2020. And since scientists don’t believe the virus is about to disappear any time soon, it’s important that as well as firefighting the current pandemic, we prepare ourselves for future outbreaks of COVID-19.

Predicting the evolution of a pandemic is a tricky business, but it needs to be done for several reasons, not least because the question on everyone’s minds is ‘when will this be over?’.

Michael Osterholm of the University of Minnesota and colleagues, published three potential scenarios of a future with the new coronavirus. What seems clear is that the end of 2020 won’t be the end of COVID-19, and that we are likely to be dealing with it for at least the next 18-24 months.

Three potential scenarios of future outbreaks

One scenario will see mini-waves of smaller outbreaks every few months, with periods of only a few cases in between. The location of the outbreaks may depend on regional variations in the sort of mitigation measures that are in place.

In scenario two, this current outbreak will be followed by a massive second wave that is twice as large and long-lasting. This is exactly what happened with the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic; a moderate wave in March 1918 was followed by an explosion in cases that September, followed by smaller peaks until early 1919.

In the third scenario, there will be continued COVID-19 outbreaks similar to what we are currently experiencing, until the end of 2022.

The only thing that will prevent all of these potential scenarios is the development of a vaccine, and if one doesn’t become available, then we are likely to have continued outbreaks until at least half of the world has been infected – only 5% of the world is estimated to have been infected so far.

What will low- and middle-income countries experience?

The second scenario is possibly the most frightening because in many countries health systems are only just about coping right now. If later this year we have a second outbreak of COVID-19 that dwarfs this one, most health systems – especially fragile ones in low- and middle-income countries – could buckle under the strain and collapse, causing utter chaos and extremely high death rates. It would also mean a return to the strict lockdowns that many countries have been under.

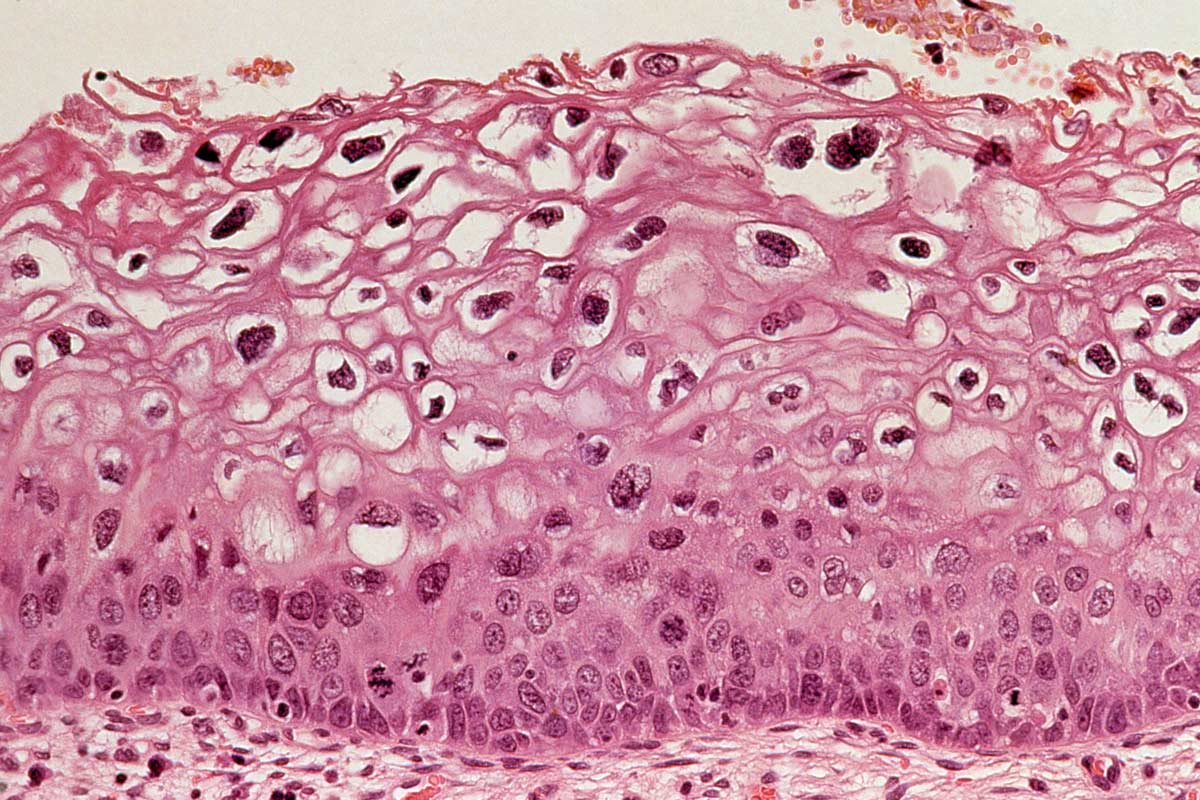

The third scenario is no less terrifying, and may be more likely to occur. Because coronaviruses can adapt well to humans and COVID-19 could keep evolving so that it is effectively a new virus to which we have little immunity. If this happens it could also potentially derail efforts to develop a vaccine.

There have been theories that heat and humidity are the reason why we have so far seen fewer cases and deaths across Africa, Asia and Latin America. Scientists estimate that although heat and humidity might kill the virus more quickly on surfaces, which may reduce transmission by about 20% in hot weather, people who are infected can still spread it through sneezing, coughing or speaking.

The best defence is preparation

The researchers strongly recommend that governments and local authorities prepare as best they can for future outbreaks – including the ability to pull the trigger on emergency lockdowns or other mitigation strategies if absolutely necessary – and for a potential worst-case scenario, where no vaccine is found to be effective, and where herd immunity cannot be achieved.

They also recommend developing strategies to ensure that health workers at the frontline of the response are adequately protected from the virus. As much as the news will be unwanted, they advise governments to develop risk communication plans to tell their populations that the pandemic is unlikely to be completely over until late 2022.