Grab, jab and release: keeping rabies off the streets of Goa

The global effort to contain COVID-19 risks disrupting campaigns against other diseases. Will the fight to control the deadly rabies virus in India be among them?

- 18 February 2021

- 6 min read

- by Maya Prabhu

The dog was already dead when he arrived on the veterinarian’s table at Mission Rabies in Assagao, Goa, one mid-April afternoon in 2020. Earlier that day, an animal lover called Diana had reported what she took for signs of rabies in the stray. “If you saw it you would exactly understand,” Diana told VaccinesWork, recalling her alarm. “He’s like… mad, you know? Mad behaviour.” The vet took a sample of brain stem tissue and pipetted it into the divot of a lateral flow assay cassette, a quick, first-line screening kit that resembles a pregnancy test. Two lines resolved: the dog was rabies-positive.

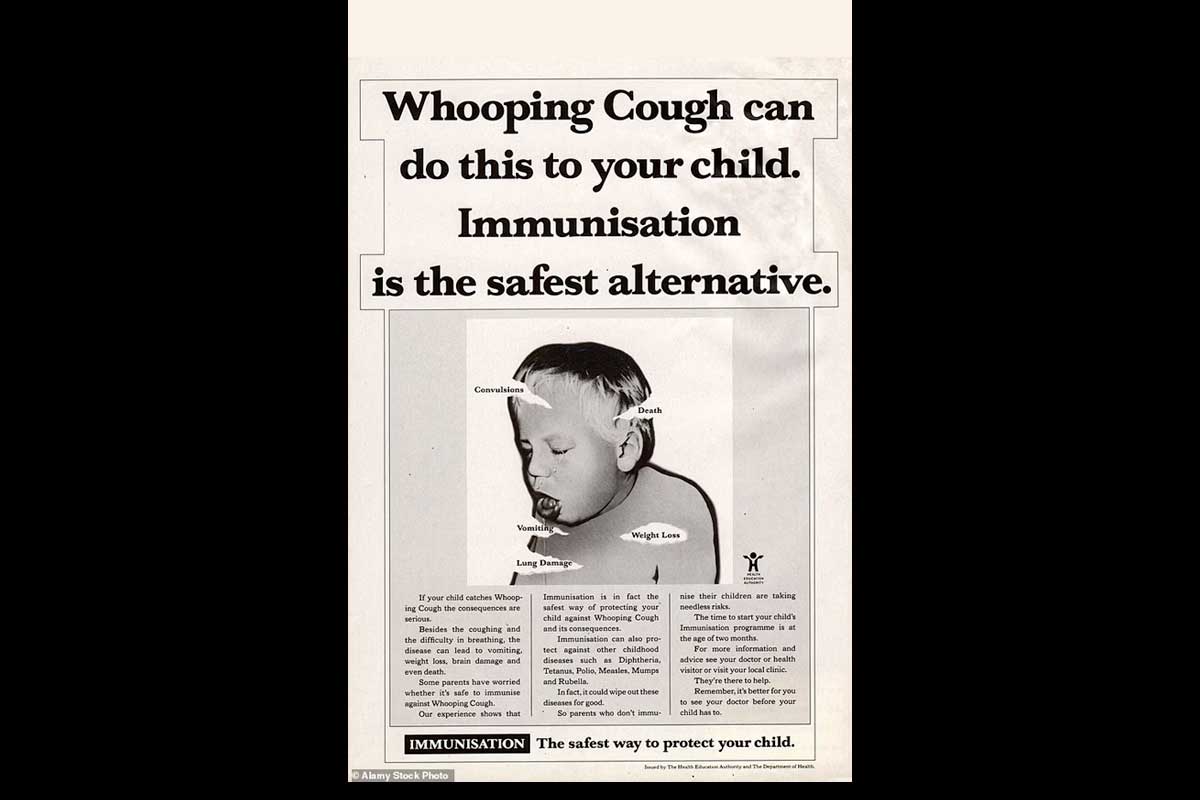

Elsewhere in India – which sees more than a third of the world’s estimated 59,000 yearly human rabies deaths, 97% of which are “dog-mediated” – one rabid dog might barely register. Goa is different. Since 2014, Mission Rabies, a charity with UK roots, has been engaged in an all-out offensive to vaccinate the coastal state’s free-roaming and “part-owned” canine population. The organisation’s squadron of yellow-shirted vaccinators, armed with dog-catcher’s nets, needles, finely-honed agility and doses of the all-important canine vaccine, grab, jab and release around 100,000 dogs a year.

Credit: Mission Rabies

Credit: Mission Rabies

The results have been striking. In 2014, the year Mission Rabies began their work, Goa’s rabies death toll stood at 15. That figure fell sharply each year until, in 2017, the state saw just a single case – a 30-year-old man who died at Goa Medical College in Panaji that September. Since then, Goa has been human-rabies free. Meanwhile, neighbouring Karnataka recorded 23 deaths in 2018 alone. Dr Gowri Yale, scientific manager for Mission Rabies explains: “if we can remove rabies from the dog population, we’ve solved the rabies problem.”

But the dog on the veterinarian’s table that April afternoon marked the beginning of an unexpected surge – one that arrived as India shut down in a bid to contain COVID-19. “It was one after the other,” recalls Yale, a veterinarian with a PhD in rabies epidemiology. Seven rabid animals surfaced by the end of April, there were even more in May. By the year’s end, Mission Rabies would record more than 20 confirmed cases. “I was disappointed, that’s for sure. I did not expect this many cases in 2020,” says Yale.

India had gone into hard lockdown in late March. Until the end of May, Goa’s streets were spookily empty, cleared by the twin threats of COVID-19 infection and strict policing. While Mission Rabies staff were soon approved to resume their duties, their work took on a new urgency. Emergency vaccination campaigns on Goa’s northern border, where most of the new rabies cases were being found, took the place of routine rounds.

Was the lockdown somehow causing a surge in canine rabies cases? It’s possible, concedes an unconvinced Yale. A colleague observed local strays roving further than usual in search of food and human contact. Similar increased canine traffic along the border with Maharashtra could have caused what Yale calls a “double-dilution” – an exodus of vaccinated dogs from the Goan population coupled with an influx of unvaccinated dogs from Maharashtra – fraying the safety net of herd immunity.

Then the lockdown lifted, the streets began to fill again and rabies cases continued to trickle in, as did new anxieties. Among them was the fear that COVID-19 – “the new chick in town”, in Yale’s words – would draw crucial resources away from rabies. Rabies is “a poor man’s death,” she says and, like other diseases of poverty, it risks being overlooked – a fact reflected in its inclusion among the 13 so-called neglected tropical diseases.

Credit: Mission Rabies

Credit: Mission Rabies

It’s also a death “no-one should go through,” according to Dr. Ramesh Masthi, a physician in Bengaluru, the capital of Karnataka. The rabies virus is uniquely deadly: in the absence of vaccination, it has a 100% fatality rate. “It’s a very painful death, a very tragic death. The person is almost conscious until the time of death,” says Masthi, who specialises in human rabies. Signs of infection usually show up within 90 days of exposure, but can take as long as 2 years. In almost every case, exposure is an animal bite, which introduces the virus via infected saliva to the human nervous system. Once there, it can travel unobstructed up the nerves towards the brain. By the time a patient exhibits the classical symptom of hydrophobia, he or she has only a matter of days left to live, usually spent under heavy sedation to control the renowned “rabid” aggression.

It’s a bleak prospect with one saving grace: the vaccines are good. Though individuals with a high risk of exposure, like Yale, receive the human vaccine preventively, most people are immunised against rabies as part of a course of post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP). Correctly and rapidly administered PEP – which includes wound-care and rabies immunoglobulins as well the vaccine – is close to 100% effective. Where there is adequate awareness and access to PEP, rabies deaths are vanishingly unlikely, explains Professor Dr. MK Sudarshan, the founding president of the Association for Prevention and Control of Rabies in India (APCRI).

But access has taken a hit during the pandemic, says Sudarshan, over the phone from his home in Bengaluru. “This COVID-19 has superseded rabies for the last 11 months.” He should know: since April 2020, Sudarshan has led Karnataka’s technical advisory committee on COVID-19, work which has taken him away from the business of rabies control, but hasn’t quite stopped him from keeping a watchful eye out on his specialism. First came the lockdown, he says – a period in which problems of access may have been balanced by reduced exposure. “Then there was a wave of COVID pandemic, the hospitals were crowded and clinics were closed – doctors were not available. From March to October – this period was most disrupted for rabies prophylaxis.”

In Goa, Yale recalls a moment of fear that the spike in dog rabies cases could lead to a human case, bringing an end to the state’s zero-human-rabies streak. But each animal diagnosis presents its own opportunity to save human lives.

In February 2021, after a month without a positive diagnosis, the Mission Rabies team identified a rabid puppy in the town of Arambol. As they always do, the yellow-shirted Mission Rabies workers filtered out into the public, equipped with photos of the puppy and an urgent message: if you’ve been exposed, get vaccinated now. They’re thorough, says Yale. “We cannot have a human death. That’s my pep talk to my staff: you have to find everyone.”