“It’s magical”: Zimbabwe’s ‘vaccines comedian’ boosts health through stern jokes

Sabhuku Vharazipi has an online following of more than 700,000 Zimbabweans, who come for the funny and leave with a message.

- 23 January 2026

- 7 min read

- by Ray Mwareya

At a glance

- The Zimbabwean comedian known as Sabkhuku Vharazipi has amassed a colossal fanbase with wry sketches that skewer anti-vaccine myths and deliver life-saving health info.

- Fans attest that Vharazipi has not only made them laugh, but changed their minds.

- Vharazipi, real name David Mubaiwa, has cracked the approachability code. “Our fans say doctors are too ‘office-like, academic’ when they talk about malaria vaccine, HPV, rotavirus – we comedians make the fans laugh first, then throw in serious messaging about vaccines, HIV testing, STIs, or gender-based violence.”

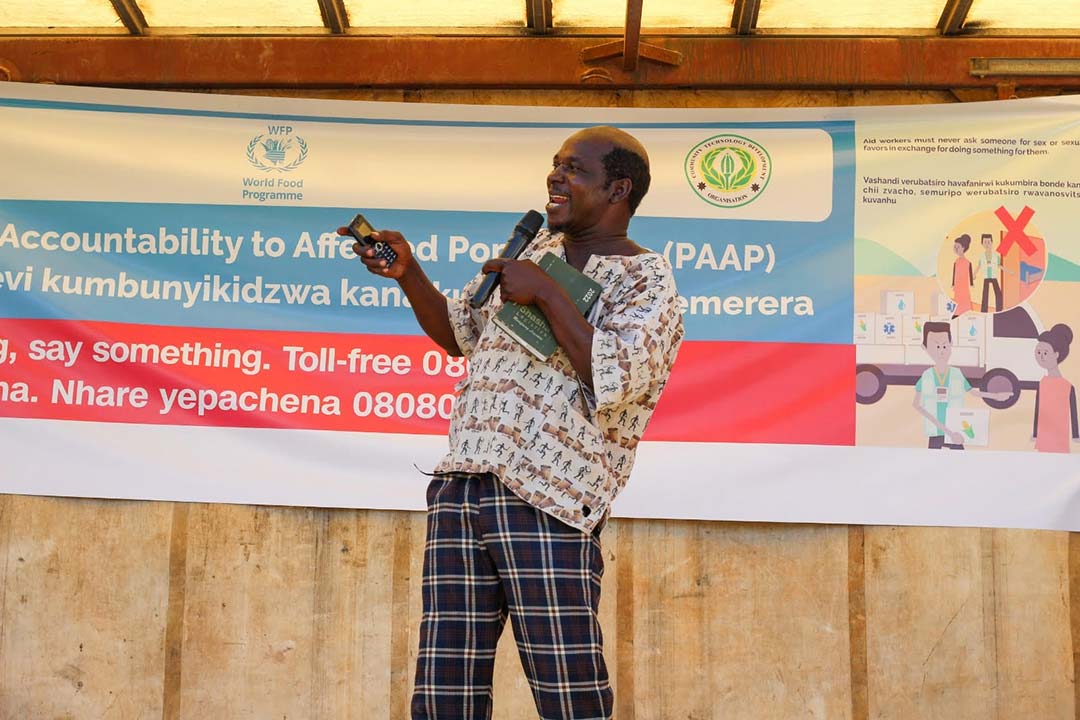

David Mubaiwa, alias Sabhuku Vharazipi, has built a massive online and offline following as Zimbabwe’s so-called ‘vaccines comedian’. The stern jokes that he and his team crack are peppered with warnings for audiences to stay up-to-date on life-and-death matters, like the human papillomavirus (HPV), cholera, tetanus, or polio vaccines.

“Through comedy skits, we are bold in telling our fans to get up to date on their cervical cancer, malaria and their babies’ ‘killer diseases’ vaccines,” Vharazipi tells VaccinesWork.

They have garnered him widespread popularity – and made him one of the go-to artists for UN agencies, public health nonprofits, and the Zimbabwe Ministry of Health whenever they want a humorous way to remind the public about preventive measures against infectious disease.

His relationship with the Zimbabwe Ministry of Health has been particularly fruitful, with early collaborations designed to generate momentum behind COVID-19 vaccines, all the way through to 2025 skits pushing parents to get babies immunised against measles, pertussis (whooping cough), diphtheria, tetanus, tuberculosis (TB), and poliomyelitis – in other words, the jabs at the core of the Zimbabwe Expanded Programme on Immunization programme.

Laughter is the best medicine

Vharazipi, though the lead actor and star face of his comedy troupe, is part of Ziya Cultural Arts Trust, which describes itself as a Zimbabwean organisation focusing on arts for social change, advancing women's rights, and gender equality through performance arts. In his skits, his most infamous sidekicks are “Chairman” (played by Wellington Chindara) an errant villager whom he berates in his comedy, and “Mbuya Mai John” (Kumbirai Chikonye), a stubborn widow who defies tribal authority.

Though his skits gain traction wherever Zimbabweans live, whether at home or in the diaspora, Vharazipi has a special place in the hearts of hundreds of thousands, perhaps even millions, of rural Zimbabweans, because he centres his work in the country’s rural heartlands. That sets him apart from the majority of the country’s comedians, who live in cities and play to an urbanite audience.

“Because my rural audiences have deeper challenges with tech, gadgets, connectivity, isolation – health messages don’t reach them faster, compared to city folk,” he says. It’s a gap he can help bridge – offline, his troupe produces plays on mounted stages, street dances and advertorials, and holds impromptu street talks with fans.

Have you read?

But his fans are online enough that he has generated a following of 700,000 on Facebook. On YouTube, he reaches a staggering 113,000 subscribers. And he manages to do more than amuse.

“Our daughter reached 10 without getting the HPV vaccine because my husband was convinced it’s a ploy to inject infertility. It’s when we heard of the scientific importance of the cervical cancer from one of Vharazipi’s comic outreaches that we were convinced to bring our daughter to the clini,.” says Marjorie Mapuranga, 35, a rural resident of Wengezi, eastern Zimbabwe, who says her family are the ‘vaccines comedian’s’ number one fans.

Vaccines in the vernacular

Vharazipi says there is a bond between audiences and comedians like him, meaning they and their families are more likely to act on public health recommendations like vaccination, HIV testing and masking up when the messaging is carried by relatable figures like him.

“In our interactions we noticed our fans also investigate on their own to see the kind of person behind the comedian whom they listen to. They check the reputation of our arts organisation, our co-comedians, and then act on their health beyond laughing at our skits,” he says. “Our fans say doctors are too ‘office-like, academic’ when they talk about malaria vaccine, HPV, rotavirus – we comedians make the fans laugh first, then throw in serious messaging about vaccines, HIV testing, STIs, or gender-based violence.”

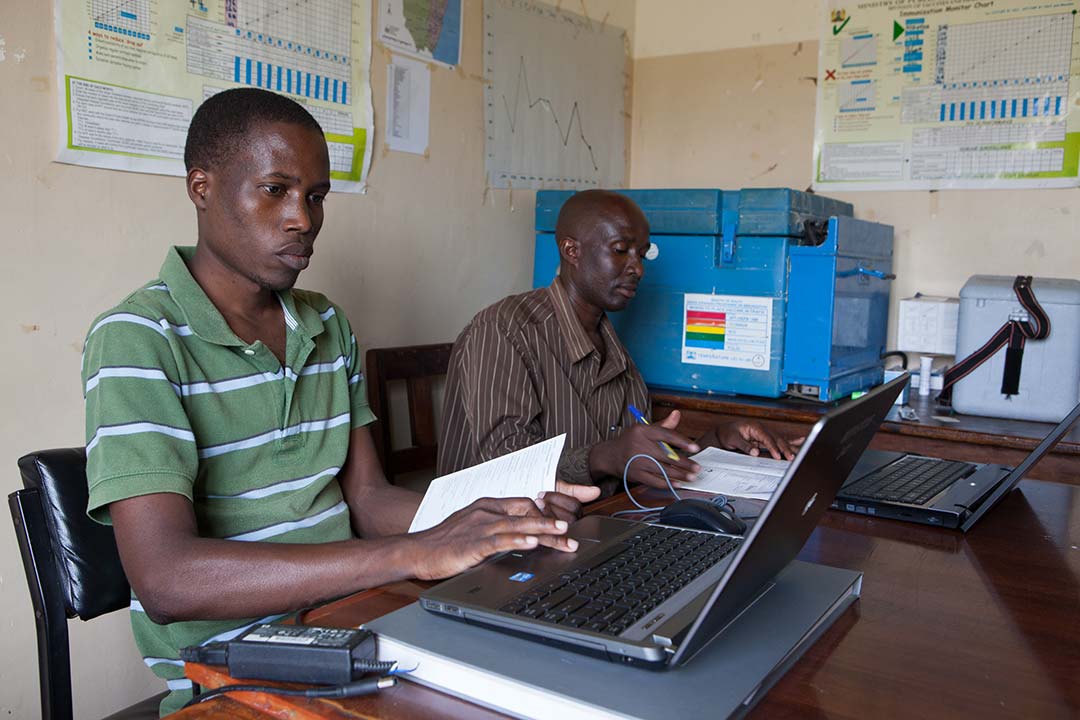

Credit: Ray Mwareya

This is why Vharazipi and his comedy troupe distinguish themselves by perfoming their comedy in their native Chikaranga, a dialect of Zimbabwe’s dominant Shona language that’s spoken in the central Masvingo province by about 2.5 million citizens in a country of 16 million.

“They deliver comedy and health messaging in our vernacular language, the language us fans are comfortable with. They don’t try to adopt a Chris Rock fake English accent,” says Makanaka Shava, 30, a mum of two in Gutu, the rural epicentre of the Chikaranga language. She says, during the COVID-19 pandemic, she was once a strict vaccines denialist. She changed her mind after seeing a Vharazipi sketch in which he played a tribal chief who verbally rebuked anyone entering his homestead courtyard maskless, or without producing a vaccination card.

Funnyman and father

Vharaziphi, born in 1973, is a father of four and a new grandfather, and says he knows the critical importance of childhood vaccines, which he says have guarded the lives of his kids into adulthood. His nous for comedy began with virtuoso roles as an actor in primary school.

“There was no TikTok then: we refined our skills acting out the scenes we read in Mills and Boons,” he says. In 1993 he and fellow actors formed a performance group that has grown over decades, and partners for health messaging with giant social-change agents like Plan International, World Vision, the Zimbabwe National Aids Council and the country’s health ministry.

“We have toured all corners of the country giving special focus to rural districts. Whether it’s comedy and theatre pushing tetanus vaccines, or adherence to HIV anti-retroviral therapy, we decided to be a mirror of rural communities, to reflect on their day-to-day lives – what excites them, their unique thoughts, their burdens,” he says.

Public health is a social question

For Shylet Sozwana, 40, a mum of two and a housewife in Chipinge, the largest rural district in southeast Zimbabwe, what is impactful about Vharaziphi’s comedy is how the dramatisation doesn’t just talk about HPV, COVID-19 or childhood vaccines in a vacuum. Vharazipi’s jokes and laughs often build from first reminding his audiences, especially men, about the societal damage of gender-based violence and how women can assert their rights and invoke the law if they are facing intimate partner violence.

“I have an example,” she says. “Vharazipi’s comedy would begin by asserting that, I, a married woman, have a right to report to police if my man threatens me with violence for going to the clinic to get an HPV vaccine without his permission. Then his skits go on to emphasise the importance of the vaccine. That kind of comedy works better on me because in my previous marriage I was a victim of intimate partner violence.”

Governance expert Tapuwa Nhachi, a consultant at the Institute for Law, Democracy and Development in Harare, Zimbabwe, agrees and reiterates: vaccination doesn’t exist in a vacuum. Vaccines are intertwined with societal gender power dynamics. A woman who is brutalised by her male partner, for example, is fearful of taking her daughters for the HPV vaccine unless she gets explicit permission. Short-term safety concerns may act against her daughters’ long-term protection against cancer.

Vharazipi agrees: “We cannot separate the two in our comedy. Violently abused women fear coming out for stuff like vaccines unless they get their husband’s permission. How couples, families eat, live, relax together determines whether women can adopt a healthcare-first behaviour,” he says. “The boldness to go and seek medical attention, be it HIV testing, cervical cancer, vaccinations, etc. is tied to peace inside a marital home.” A 2022 South African Journal of Psychiatry study found out that women experiencing Intimate Partner Violence are more likely to have adverse health outcomes ranging from more HIV infection, giving birth to low weight babies, higher substance abuse, missed healthcare appointments and so forth.

Other folk artists express support for Vharazipi’s social project. It’s commendable that NGOs working in the public health space in Zimbabwe, and the Ministry of Health are engaging comedians like Vharazipi on the critical messaging of vaccines and infectious diseases of critical concern like HIV, says Senior Musareketa, an award-winning guitarist and comic songwriter based in Chimanimani, a rural east Zimbabwe district.

“In the past, public health messages were left to nurses, doctors, headmasters – the elite class. Rural folk didn’t engage with those professionals frequently, unlike city dwellers. With comedians, any shout about measles vaccines gets amplified, because Zimbabwe people love their comedians, and when vaccine messages get mixed with skits, it gets magical.”