A little less hesitation, a little more action - Elvis and the polio vaccine

As political and public health leaders across the world work to encourage people to get vaccinated against COVID-19, what can they learn from the King of Rock ‘n’ Roll getting jabbed?

- 5 March 2021

- 5 min read

- by Tetsekela Anyiam-Osigwe

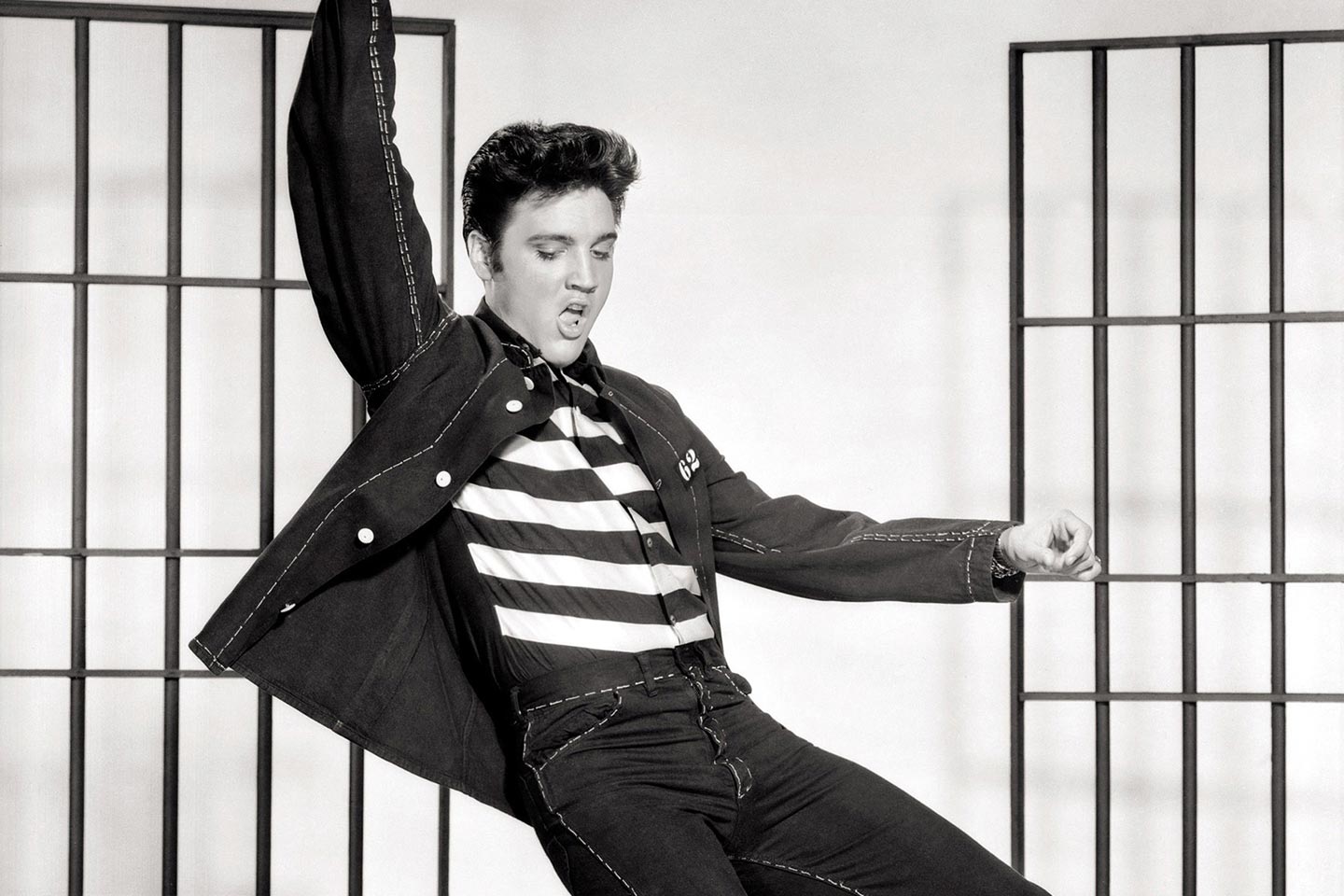

On September 9, 1956, about 60 million people – 82.6% of television viewers at the time – watched Elvis Presley give his first performance on one of the most popular television variety shows in the United States of America (USA). The massive audience tuning in for that “Ed Sullivan Show” episode was not surprising. “Heartbreak Hotel” had been a hit for the singer, peaking on the music charts earlier in the year, and while he was not yet deemed the King of Rock ‘n’ Roll, Elvis Presley was certainly on his way to global stardom.

Public health officials in the USA, who had long been trying to manage the spread of the polio virus, took notice of Elvis Presley’s wide reach among Americans. After all, they were trying to change the minds of young people – likely Presley fans – in a difficult public health situation. The polio vaccine was available to help America finally become polio-free, but many teenagers were choosing to forego getting vaccinated. Encouraged by the overwhelming public interest in Elvis Presley, health officials recruited him, and plans were put in place for his next appearance on the “Ed Sullivan Show.” Just before he took the stage to perform his hit version of “Hound Dog” that October, Elvis, smiling jovially at the cameras, rolled up his sleeves and let a New York state official inject the polio vaccine into his arm.

All jabbed up

He is setting a fine example for the youth of the country.

Even though the peak of the outbreak in the US had occurred four years earlier and the polio vaccine had now been introduced, teenagers – the most at risk after young children – remained reluctant to take the vaccine. In fact, according to The New York Times, only 10% of New York City’s teenagers had been vaccinated at the time of Elvis’ appearance on the “Ed Sullivan Show.” For New York City’s health commissioner, the then-21-year-old Presley was to set an example for teenagers across the country to follow.

Elvis’ vaccination did end up being a crucial moment in the campaign to encourage polio vaccinations. Importantly, it helped spark a national conversation among young people, which created space for the real game changer to emerge – health activism among teenagers themselves. With the help of the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis, teenagers formed Teens against Polio, organising volunteer divisions to fight polio. Using a variety of methods to encourage vaccine uptake, including a “no shots, no dates” policy in which young women refused to court unvaccinated men, Teens Against Polio helped to convince other teenagers to get vaccinated.

The polio vaccine had Elvis. How about the COVID-19 vaccine?

You going to give me the shot?

Sitting down with his upper arm open to receive his first dose of the COVID-19 vaccine, actor, producer, and director Tyler Perry was not only televising his own vaccine shot, but also using a half-hour television special to ask top medical experts about the COVID-19 vaccine. In a series of socially distanced one-on-one interviews, Perry draws on their expertise to better understand how the vaccine was developed, the mechanism through which it works and its safety and efficacy.

Have you read?

Whilst it was not the Elvis moment on primetime television, it was a much-needed effort by a public figure to share his own experience and learn alongside his audience as the world looks to mass vaccinations as the best possible route out of the acute phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. Indeed, since COVID-19 vaccines have been approved and rollouts have begun, numerous celebrities and politicians have joined Perry by publicly sharing photos and videos of themselves getting vaccinated in order to encourage vaccine uptake among the general public.

Ultimately, it’s the vaccines for me.

Amid all this, there remains the question of whether public figures can actually convince an otherwise hesitant public to get vaccinated. Even in Elvis’ case, it is difficult to categorically conclude that his televised shot single-handedly led more teenagers to take the polio vaccine. Rather, it called young people’s attention to the vaccine itself, compelling them to seek out more information about it and inspiring activism among teenagers.

As people decide whether to get vaccinated against COVID-19, what seems to matter is less about the ‘likeability’ of the celebrity or politician who urges a fanbase or constituency to get vaccinated, but the kind of conversations and concrete actions that they can spark among people. Arguably, given the sheer amount of competing information regarding the COVID-19 pandemic, it’s more important to encourage people to think about the important aspects of the vaccine itself – the scientists who developed them, the pharmaceutical companies manufacturing them, the results of clinical trials, various regulators’ assessments, and the advice of medical professionals.

Public figures, by contextualising their COVID-19 vaccine shots with honest individual stories and narratives and accessible Q&As with credible and reliable experts, can encourage us to focus our attention on the facts about the vaccine and what informed their decisions to ultimately get vaccinated. In a time of COVID-19 misinformation overload, perhaps this is what medical experts, national and international health agencies, and governments around the world should hope for when the next public figure decides to get all jabbed up.