Mali: HPV vaccination takes root one year after its introduction

Despite challenges, momentum behind the cancer-blocking jab is building in Bamako, and around the country.

- 8 December 2025

- 5 min read

- by Aliou Diallo

At a glance

- In just the first nine months of 2025, more than 145,000 ten-year-old girls in Mali were vaccinated against the cancer-causing human papillomavirus (HPV).

- Misinformation connecting the vaccine with infertility has slowed uptake in places, but health workers report that patient explanation in local languages has helped ease that block.

- “My mother-in-law suffered from cervical cancer and died from it this year. I’ve seen with my own eyes how much a woman can suffer. So I preferred to protect my daughter, so she never has to face that,” said Fannata Dicko, mother of a vaccinated girl.

On Thursday 30 October, in the Korofina neighbourhood of Bamako, an information session brings together women and young girls at the local civil registration centre. Midwife Amin Dem opens the discussion. “At the beginning, there was a lot of reluctance. The girls were afraid, and the parents as well. But with awareness-raising, things have changed,” she explains.

Credit: Aliou Diallo

According to her, the main concern remains the myth that the vaccine would make girls infertile. “When you take the time to explain – especially in their own language – they understand.”

A major breakthrough in prevention

Introduced in November 2024, the HPV vaccine represents a real turning point for the country. More than 145,000 ten-year-old girls were vaccinated with the single-dose vaccine between January and September 2025.

A little over 113,000 of those girls were in school, while around 32,400 out-of-school girls were also reached. Authorities acknowledge, however, that further efforts are needed to reach this group, which is more at risk of being left behind.

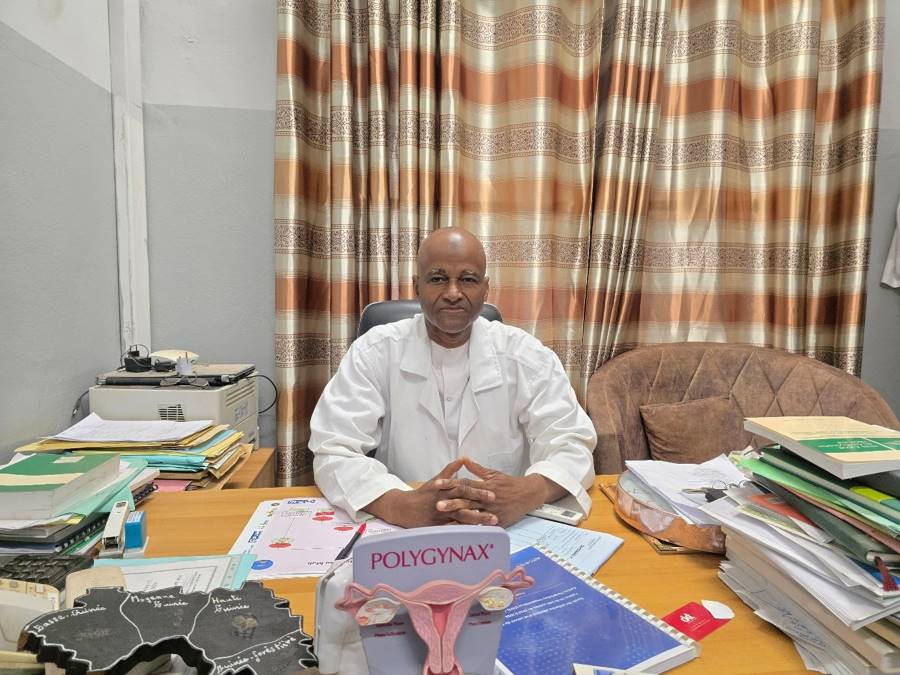

Dr Ibrahima Téguété, gynaecologist-obstetrician at Point G University Hospital, says Mali is making strides towards the WHO 90-70-90 cervical cancer elimination targets: vaccinating 90% of girls against HPV, screening 70% of women at two key ages, and ensuring treatment for 90% of women with lesions.

“Introducing the vaccine is a great satisfaction. It finally allows us to act on primary prevention,” he emphasises. He remains realistic about the system’s constraints: “We have only one radiotherapy unit. The last ‘90’ will be hard to reach for now.”

Collective mobilisation as a key driver

While the campaign is anchored in public health structures, civil society also plays a major role. In Bamako, the NGO Solidaris223 has multiplied awareness sessions since the launch.

“We worked in every commune. Mothers came to ask where they could get their daughters vaccinated,” explains its president, Amina Dicko.

Credit: Solidaris223

At the Centre Djiguiya in Bamako, an entire day was dedicated to vaccination. “Seventy boarding students received their dose, and none had any side-effects,” says the director, Togo Mariam Sidibé.

Awa, ten, confides: “I was scared of the needle, but it went fast. I’m happy because it protects us for the future.”

Haby, vaccinated at school and interviewed at home, said, “Our teacher explained why it’s important. I asked my mother, she reassured me. I’m proud to be vaccinated.”

Dr Téguété, was gratified by the enthusiastic popular response: “The first vaccine shipments were used very quickly. It proves there is collective will.”

Hesitancy decreasing – but still present

Rumours about infertility continue to fuel a portion of resistance. “Some people want others to believe the vaccine is a way to harm us. That’s completely false,” insists Dr Téguété.

Amin Dem sees the shift daily: “Now some mothers come on their own asking for the vaccine. As soon as you take the time to explain, everything changes.”

Credit: Aliou Diallo

For Fannata Dicko, mother of a vaccinated girl, there was no question. “My mother-in-law suffered from cervical cancer and died from it this year. I’ve seen with my own eyes how much a woman can suffer. So I preferred to protect my daughter, so she never has to face that.”

Despite progress, vaccine deployment still faces real obstacles. “Between Mopti and Gao, travel is sometimes impossible by road,” notes Dr Téguété. To address this, some shipments are flown directly to regional capitals.

The vaccine remains available entirely free-of-charge for all ten-year-old girls, thanks to joint efforts from the government and its technical and financial partners – including Gavi, which enables Mali to access the vaccine at a reduced cost. This ensures equitable access, even in remote areas.

“If we can maintain this effort for a few more years, we will have vaccinated all girls aged 9 to 14,” estimates the specialist.

Have you read?

A horizon of hope – despite challenges

Prevention efforts did not start yesterday. Between 2016 and 2022, the Weekend 70 programme increased cervical cancer screening rates from 15% to over 70% in the Bamako district. But misinformation remains a major obstacle. “People fear what they don’t understand. We must keep explaining, informing, talking,” insists Dr Téguété.

He also praises the role of religious leaders: “Their support has greatly reassured families.”

In Bamako, results are visible: parents are more confident, and more girls are getting vaccinated. “Bamako is not Mali, but it is a good indicator of what we can accomplish together.”

Midwife Amin Dem shares this optimism: “Before, people asked why we talked about cancer here. Now, they come looking for answers.”

For professionals and associations alike, the HPV vaccine marks the beginning of a profound transformation in women’s health in Mali. And as Dr Téguété reminds us:

“Behind every vaccinated girl, there is a woman saved.”

This article is a translation from the French. Read the original here