Mpox is no longer officially a public health emergency; here’s why we shouldn’t let down our guard

While the global outbreak of mpox is easing, the disease continues to circulate and people in Africa and Latin America have few vaccines or treatments.

- 12 May 2023

- 5 min read

- by Priya Joi

Mpox (formerly called monkeypox) is no longer a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC), according to a statement by the World Health Organization (WHO), at a meeting of its experts on 10 May 2023.

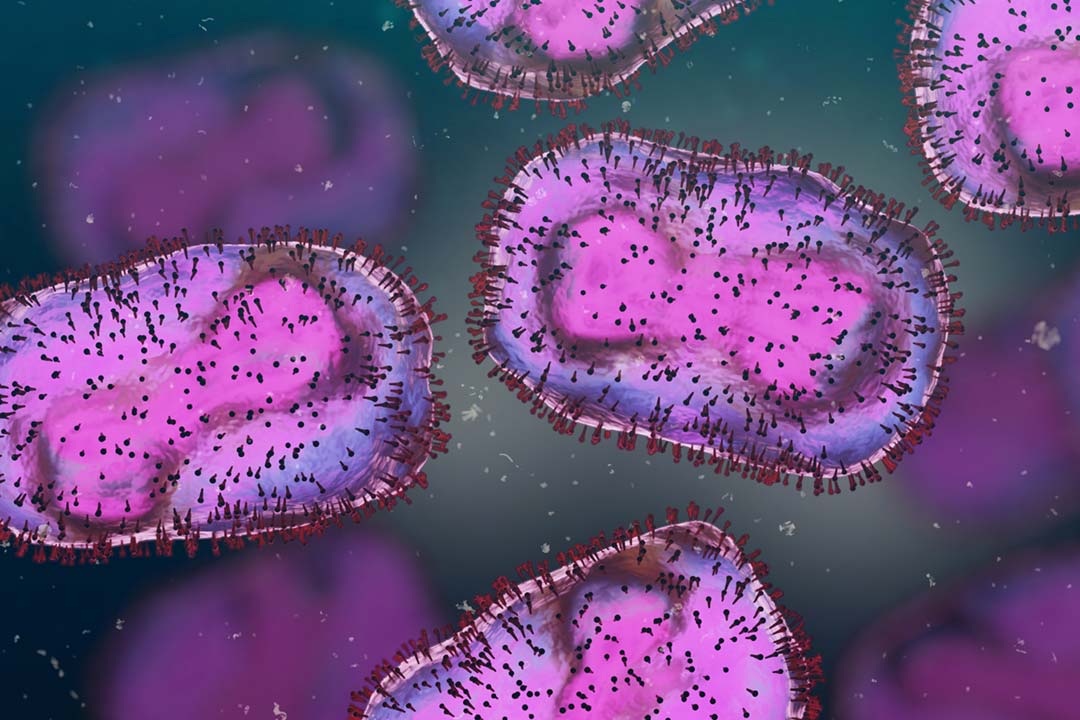

The disease, which causes fever, muscle aches and boil-like skin lesions, has been spreading rapidly since May 2022, when it first came onto the global radar with an outbreak of cases in the UK, outside of normally endemic countries in Africa. In May 2022, there were 3,040 cases from 47 countries; in July 2022, when WHO declared it a public heath emergency, there were 14,533 cases from 72 countries. Now, a year later in May 2023, more than 87,000 cases and 140 deaths have been reported to WHO from 111 countries.

Africa has had a 7.4% case increase, with 111 new cases in the most recent two weeks – the Democratic Republic of the Congo has seen a 23.6% increase in cases in recent weeks – indicating that the disease is still a health threat.

The announcement comes as Africa has had a 7.4% case increase, with 111 new cases in the most recent two weeks – the Democratic Republic of the Congo has seen a 23.6% increase in cases in recent weeks – indicating that the disease is still a health threat.

A PHEIC is the strongest global alert the World Health Organization (WHO) can formally make and its declaration under the International Health Regulations (IHR) means that countries have a legal duty to respond quickly, with a clear set of measures and legally binding obligations for a coordinated international response. Crucially, it also requires countries to share data on cases and deaths, and new genetic information that may be sequenced.

By contrast, even when a disease is characterised as a pandemic there is no specific infrastructure that determines how countries respond and how they collaborate with each other.

But the process of deciding which disease meets the requirement of a PHEIC, and when to declare one over, is complex.

Have you read?

For instance, when WHO's emergency committee met in July 2022 to discuss the outbreaks, the committee could not come to a consensus on whether to declare it a PHEIC or not. It was WHO's Director-General Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus who made the decision to declare it a public health emergency and sound the global alarm.

The decision almost a year later to declare the public emergency over, he says, is because, "There were almost 90% fewer cases reported in the last three months, compared with the previous three months."

The problem is there are many unknowns about mpox. It is still not clear why it suddenly started spreading outside of Africa last year. While the WHO committee acknowledged that while much is still unknown about modes of transmission in some countries, and there is poor quality data and continued lack of effective countermeasures in Africa, a continued designation as an emergency would not be the way to address it.

Instead, they suggest "sustained efforts in a transition towards a long-term strategy to manage the public health risks posed by mpox, rather than the emergency measures inherent to a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC)".

In the global outbreak of mpox, 98% of cases are in men who have sex with men. In February 2023, researchers found a necrotising form of mpox with a high fatality rate in people with advanced HIV.

In most people, mpox causes a few skin lesions that clear up in a few weeks. However, the aggressive form of the disease causes skin ulcers that continue to grow and even spread to the lungs, eyes and intestines.

As with many diseases, there are huge inequities in access to vaccines and antivirals globally – and most countries in Latin America (where many of the cases are outside Africa) and Africa don’t have vaccines and treatments for mpox.

As Oriol Mitjà, lead author of the study published in The Lancet, said: "We don't call it necrotizing because of its speed, but because it doesn't stop. It goes on and on and on. No matter how many actions you take, the virus continues to progress."

Chloe Orkin, Professor of HIV Medicine at Queen Mary University of London, UK, told VaccinesWork this means that "Everyone with mpox needs to be tested for HIV. If someone has HIV and gets mpox, their CD4 count must be measured urgently to see whether they're at risk."

However, as with many diseases, there are huge inequities in access to vaccines and antivirals globally – and most countries in Latin America (where many of the cases are outside Africa) and Africa don't have vaccines and treatments for mpox.

This means that surveillance and reporting is more critical than ever, and that global attention shouldn't wane just because the disease is not categorised as a public health emergency any more. Back in October, The Lancet warned that just because monkeypox is currently controllable, it might evolve, and might not be easily controllable in future. Cases may be declining globally, but this statement remains as true as ever.