Paper jam: Ugandan vaccinators ditch old school ledgers and trial digital alternatives

Saving nurses the time they spend paging through registers of patient details is good for public health.

- 2 November 2023

- 5 min read

- by Dicta Asiimwe

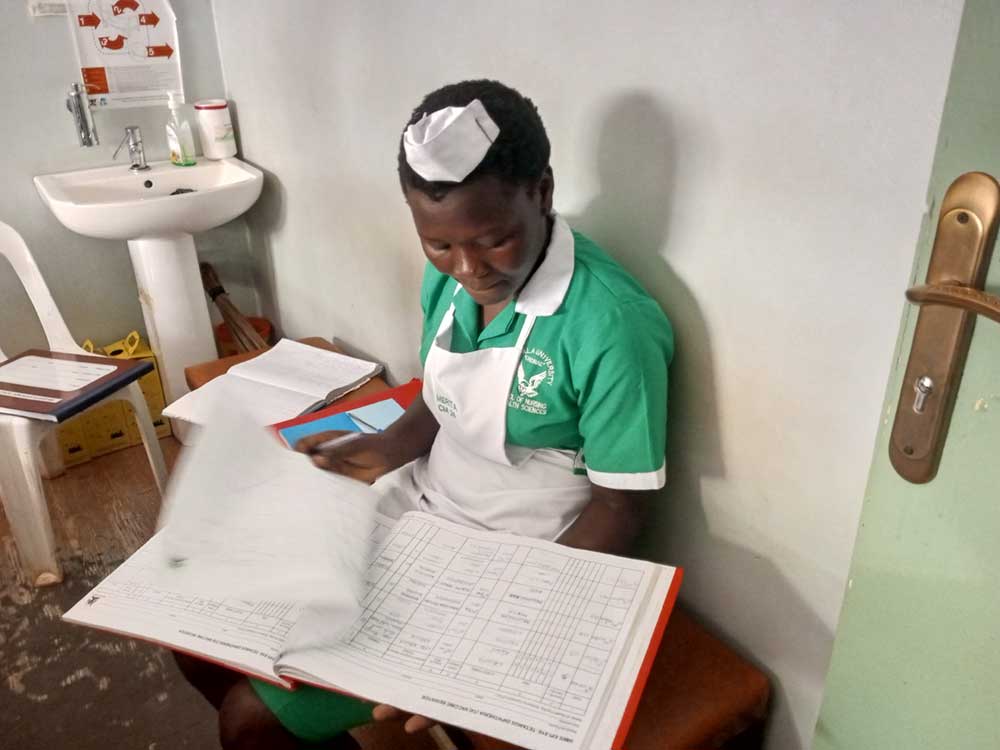

Seated on a bench in the small immunisation room at Mukono General Hospital, Mekita Merita, a student midwife from Kampala University, patiently leafs through a large Ministry of Health registration book.

Around her, two other health workers are caring for patients – injecting thighs or putting vaccine drops in babies' mouths. But Merita's assignment on this day is clerical: to make sure every adult immunised against hepatitis B is properly registered.

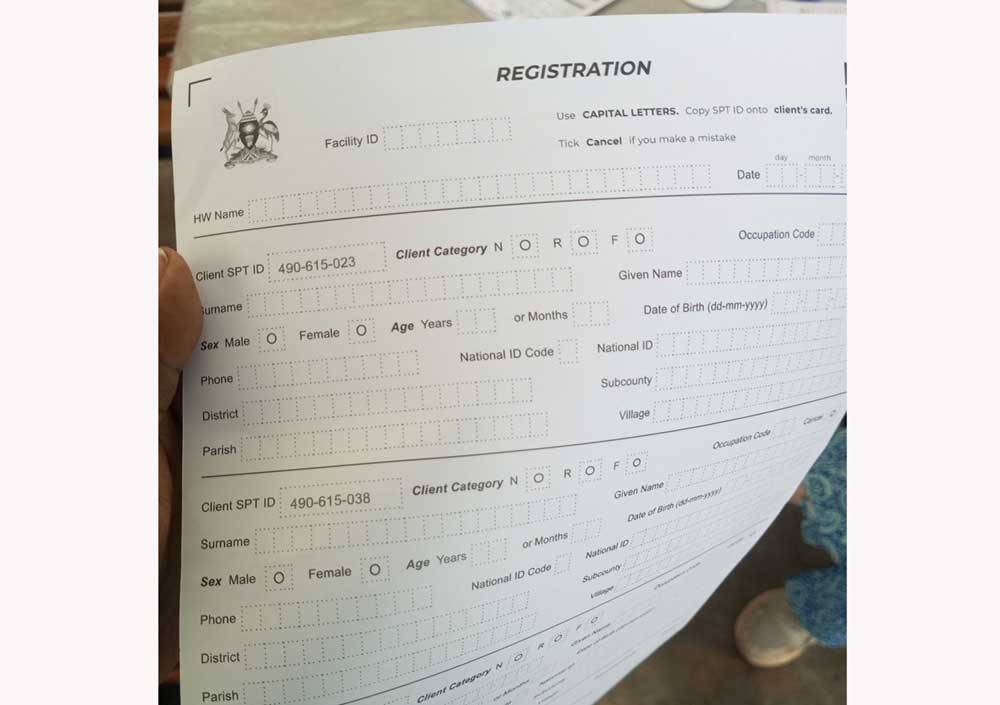

Unlike the traditional registration book, from which data must be manually read, and then manually fed into the DHIS2, SPT is scannable, and automatically uploads details such as the child’s name, their parents’ identities and phone numbers to the system.

It's important work, if not exactly exciting. Later, the hospital's medical records office will pick up the data she records and feed it into the District Health Information System 2 (DHIS2), the tool that Uganda uses to aggregate data on disease, immunisation, and other medical interventions made by health workers across the country.

Credit: Dicta Asiimwe

Because the hepatitis B shot is not a routine vaccine for adults in Uganda, it is one of the few that is still being recorded manually in the registration book. It takes Merita no less than three minutes to find and input the information for a single vaccination: a second dose received by a single patient in late September.

Paper cuts

Scaled up, those three minutes equal a health system logjam. "The time it takes to find just one name, for someone who was at the hospital only a month ago, would be a problem in times when there are no internship students to do that kind of work," says Dr Anthony Kkonde, the Principal Health Officer for Mukono Municipality.

Mukono General's medical records show that on average, the hospital vaccinates 100 clients each weekday. This means that if the three minutes it took Merita to register a single jab were standard across vaccines, recording a day's immunisations would cost five hours of a health worker's time.

Dr Kkonde points out that the friction created by register management has the potential to erode vaccination rates. Mukono General Hospital typically assigns two health workers for immunisation, he says. With one person manning the books, long queues – and consequently long wait-times – are likely. That, in turn, might well discourage some parents from returning to vaccinate their children.

Credit: Dicta Asiimwe

Additionally, data quality can suffer. "Because this is a high-volume hospital, such a small workforce taking time to properly register the details of the vaccinated child would be very cumbersome, so the nurses often neglect this part of the job," he says.

Practically, that neglect might mean that ledgers concerning vaccine stocks are updated, but the child's status skipped, creating gaps in health system oversight about who is or is not fully vaccinated.

Scannable records to the rescue

Dr Kkonde is, therefore, deeply appreciative of the Karolinska Institute, a medical institute in Sweden, and Makerere University's Department of Biomedical Engineering. Together, these two institutions have come up with, and refined, the Smart Paper Technology (SPT) that is now used in Mukono's health facilities to register details of children and some adults seeking immunisation services.

Have you read?

Albert Besigye, the Monitoring and Evaluation Specialist for the Uganda National Expanded Program on Immunisation (UNEPI), says SPT has so far been adopted on a pilot basis in 14 districts, including Mukono. "SPT, as a system, is helping us to uniquely identify a child," Besigye explains.

Credit: Dicta Asiimwe

Unlike the traditional registration book, from which data must be manually read, and then manually fed into the DHIS2, SPT is scannable, and automatically uploads details such as the child's name, their parents' identities and phone numbers to the system.

"It helps in giving us an electronic child register," he says.

Clients registered on smart paper get unique identification numbers. These make updating vaccination details easy, says Besigye, because health workers no longer have to page through voluminous ledgers to find a client before entering information on the day's new jab.

The health worker simply notes down the SPT number, marks the vaccine taken, and then that data is scanned and automatically uploaded into the system.

"With all those details, we are even able to [automatically] generate and send phone messages as reminders for parents not to default on their children's vaccination," says Dr Kkonde.

Johnson Mbabu, the Medical Records Officer at Mukono General Hospital, adds that the smart paper is helping streamline the ongoing COVID-19 vaccination roll-out.

Using the SPT system, Mbambu says they can rapidly upload data onto EPIVAC, which is a portal hosting COVID-19 vaccination details, so that members of the public can print their vaccination cards to travel internationally or when accessing restricted public spaces.

Storage woes

Besigye says the one challenge with SPT – and the reason it has not been rolled out nationwide – is that it requires a lot of data storage space that is not yet available in Uganda.

"It is not working as we expected, because according to Uganda's data policy, data must be hosted on in-country servers, but this SPT system was hosted in the cloud," he says.

Because no solution to the storage space concern has been found, Besigye says they are now trying out alternative systems to easily digitise immunisation data.

One of the tools currently in the works is a national electronic community health information system (eCHIS). Besigye says that under this system, the Ministry of Health registers every child in the community to identify the children that have not been immunised or have not completed their vaccine shots.

Mbambu, however, says there is a pause in implementation of the electronic community health information system.

Villages health team (VHT) members that VaccinesWork interviewed for this story say the government has provided phones, to be used to take and update details for different people, especially children under five and pregnant women. The government also trained the VHT members in August, but at the time of writing, the system is not yet widely operational.