Shame, myths and needlephobia leave Ugandan women at high risk of preventable cancer

Cervical cancer is vaccine-preventable in 95% of cases. It also remains Uganda’s single most common cancer, affecting three times as many women and girls there than on global average. VaccinesWork finds out why.

- 7 March 2023

- 7 min read

- by Dicta Asiimwe

Rebecca Kisakye considers taking the vaccine against the human papillomavirus (HPV) one of the most valuable things she got out of school. At 16, Kisakye is no longer enrolled, having last sat in a classroom in 2020, when Uganda locked down to stop the spread of COVID-19.

“I cannot imagine enduring that kind of pain and suffering that cancer brings because I feared getting an injection.”

– Rebecca Kisakye, 16

Credit: Dicta Asiimwe

She didn’t want to drop out. But by the time schools fully reopened in February 2022, Kisakye could no longer afford to go. Her 62-year-old paternal aunt, Rose Nanyondo, had been paying her school fees, but a bout of ill health suddenly tanked Nanyondo’s financial fortunes.

At home during the first wave of the pandemic, Nanyondo found a lump in her breast. Trips to different health facilities finally led her to the Uganda Cancer Institute (UCI), where VaccinesWork found her waiting for the fifth of six rounds of chemotherapy.

“The chemotherapy affected my legs and at some point my relatives and friends thought I would not make it, but I now feel better and my breast has gone back to normal,” says Nanyondo.

Credit: Dicta Asiimwe

The rest of her life has not. Before the cancer struck, Nanyondo, a farmer, had been using some of her income to fund her niece’s education. Since the cancer, Nanyondo has been too weak to farm.

Because of that, teenaged Kisakye now splits her time between farm work in Masaka, located more than 130km from Uganda’s capital city, and acting as her aunt’s attendant when Nanyondo is at the UCI in Mulago, Kampala.

Nanyondo cannot stand on her own, so Kisakye props her up when she goes to the doctor’s office, helps her go to the toilet, and takes over much of her aunt’s medical administration.

“I cannot imagine enduring that kind of pain and suffering that cancer brings because I feared getting an injection,” says Kisakye, pausing in the hallways of UCI, where she is trying to locate her aunt’s missing treatment file.

“The truth is to improve HPV vaccination we need a lot of mobilisation to get rid of the myths.”

– Dr Alfred Jatho, Uganda Cancer Insitute

Kisakye says that even if the HPV vaccine only prevents cervical cancer – in fact, the jab can also prevent HPV-linked cancers of the throat, vulva, vagina, penis and anus – that is at least one less cancer to worry about. The potential cost to you and your loved ones, she says, is too high to ignore.

And the risk is higher in Uganda than in most places. Cervical cancer is the single most common cancer among Ugandans, who suffer an incidence three times higher than the global average. Data from the Global Cancer Observatory shows that in 2020, cervical cancer accounted for 20.5% of the 34,008 new cancer cases registered in Uganda that year. More than nine out of ten cases of cervical cancer are attributable to HPV, which means that almost all cervical cancers could have been avoided by vaccination.

Yet many parents, especially those who live in Kampala, still do not believe getting the HPV vaccine is important. Eight out of ten people interviewed for this story as they waited to see a health worker at UCI’s Early Detection Unit either did not know or did not want their girls getting the HPV vaccine.

Have you read?

“Would you take your daughter to get that vaccine? I wouldn’t want my daughter vaccinated, because in any case, I have grown up to this age without getting cervical cancer,” said the mother of a 15-year-old girl.

Another parent, a father of three girls, says he does not want his daughters vaccinated. He says his children are Christian-raised and will abstain from sex until marriage, at which point, he claims, the odds of getting cancer via the sexually-transmitted human papillomavirus are low.

Dr Alfredo Jatho, researcher and head of the Early Detection Unit at UCI, says part of the problem is that the HPV vaccine is relatively new and the government has not had enough time to dispel the myths and misconceptions around it.

He says that while routine vaccination for children under nine months has been around for a very long time, it is not the same for HPV, which first rolled out Uganda-wide in November 2015.

“During a sensitisation meeting one parent once asked us whether the HPV vaccine wasn’t a contraception method being disguised as a cancer prevention method,” says Dr Jatho.

Information from the Uganda National Expanded Programme on Immunisation (UNEPI) shows the uptake of the HPV jab remains low.

Dr Immaculate Ampaire, the HPV immunisation focal person for UNEPI, shared data showing that last year, 176.2 out of every 200 eligible girls got the vaccine. However, second-dose coverage was quite poor, with only 66.1 in every 200 eligible girls getting their shot.

A 2022 study published in the journal PLOS ONE found similarly sub-standard protection among girls attending the adolescent clinic of Mulago hospital. Just 43.3% of surveyed girls had completed their two-dose series on time, found the researchers, who characterise that figure as “low” but “higher when compared to earlier published reports”.

“You are not fully protected if you don’t get your second shot,” emphasises Dr Jatho.

Pauline Picho, Executive Director of Nama Wellness Community Centre (NAWEC), a not-for-profit organisation that provides reproductive health services to the semi-rural parts of Mukono district, says the other problem is that there is stigma around cervical cancer, which affects parents’ willingness to protect their children against the disease.

Credit: Dicta Asiimwe

Data segregated according to sex shows that cervical cancer constituted a third of the registered cases among women at UCI that year. Yet, you would not know that cervical cancer has such a high incidence by just interviewing patients and caretakers waiting for treatment in the corridors and verandahs of UCI at Mulago hospital. Many women told VaccinesWork they were either treating throat or breast cancer.

“Cervical cancer patients do not want to talk about it because it has been stigmatised. A significant proportion of cervical cancer patients are positive for HIV/AIDS so some members of the population stigmatise both,” says Christine Namulindwa, the UCI spokesperson.

Picho, whose organisation works with members of the Seventh Day Adventists (SDA) to run an annual health camp, says women often refuse to screen for cervical cancer in fear of stigma.

In addition to the provision of contraceptives, NAWEC provides treatment for ailments such as malaria and malnutrition and routine vaccination at their clinic and during outreaches.

Teddy Neema Bashenyi, the Project Manager in charge of NAWEC’s community Health Action Programme, says parents often bring in children for vaccination against childhood diseases such as polio and measles. However, it is different for HPV, as eligible girls rarely seek out the preventive immunisation.

Instead, when it comes to HPV, NAWEC often brings the vaccination to pupils in schools, as this saves time and ensures that eligible girls do not miss out.

“The problem with government’s current approach is that they often wait for eligible girls to come to facilities and this rarely happens. They have vaccines but don’t take them where people need them,” says Neema.

However, Ampaire, the Ministry of Health’s HPV immunisation lead, says the government has found a solution to the problem of girls rarely going to health facilities for the HPV vaccination.

“We now do most of the vaccination through outreaches during the months of April and October,” she says.

And yet, concentrating on the months of April and October can create a different set of problems. Neema says in some cases condensing the campaign can create stock outs. While NAWEC and other facilities in Mukono, on the outskirts of Kampala, currently have HPV vaccines, the purple cards given to girls to certify that they have been vaccinated are not available at the moment.

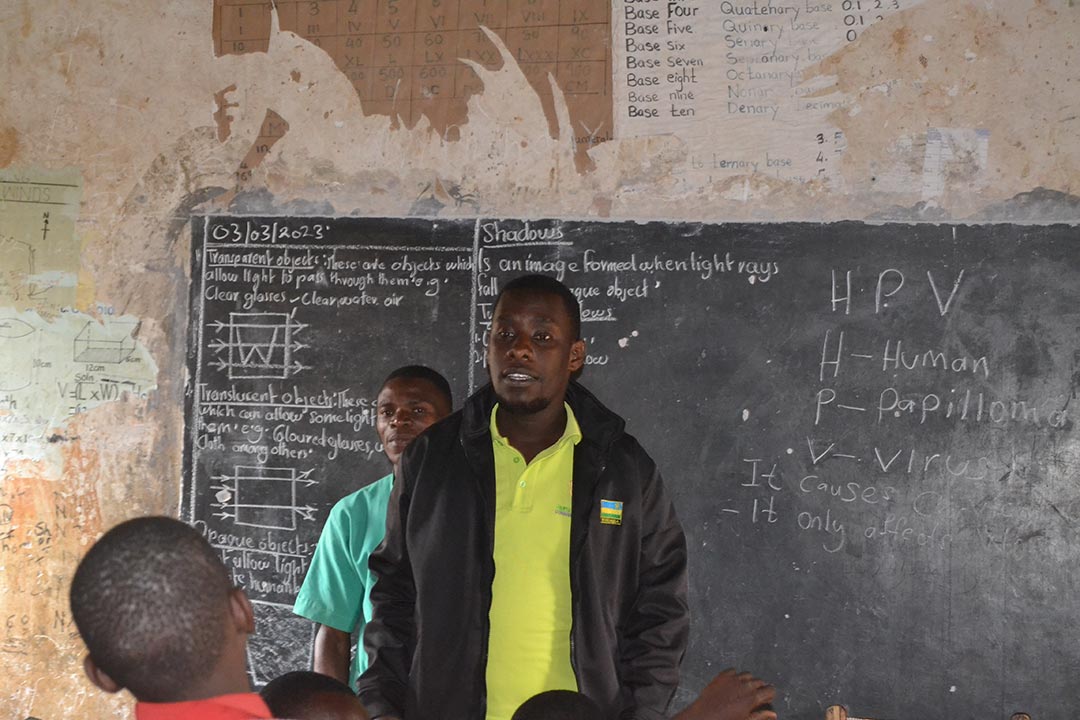

The lack of cards creates some challenges. At Bright Valley Walusubi and Charity Universal primary schools, for example, where NAWEC vaccinated more than 130 girls on 3 March, some girls grew confused, believing that the COVID-19 shots they had received were HPV vaccinations.

Girls with injection-phobia also try to lie their way out of getting the vaccine. Fearing injections is the only reason cited by the pupils we spoke to who admitted attempting to dodge taking the HPV vaccine.

While the schools, located in semi-urban and rural areas, enthusiastically vaccinate their eligible girls and have asked for more services, like on-site tetanus immunisation, Neema says things are harder when it comes to dealing with pupils in private schools, whose parents tend to be wealthier. She says rich private schools often say parents are against giving their children HPV vaccines.

Neema believes it is because these parents have their children immunised against HPV at private health facilities. The in-charge at the Reproductive Health Uganda clinic, located close to upscale neighbourhoods in the capital, however, says the clinic got rid of their HPV vaccine refrigerator last year due to lack of uptake. She says many parents who came out to the clinic seeking contraception reject HPV vaccination, parroting misinformation from the internet to justify their choice.

“The truth is to improve HPV vaccination we need a lot of mobilisation to get rid of the myths,” says Dr Jatho.