Six rules to tackle health misinformation

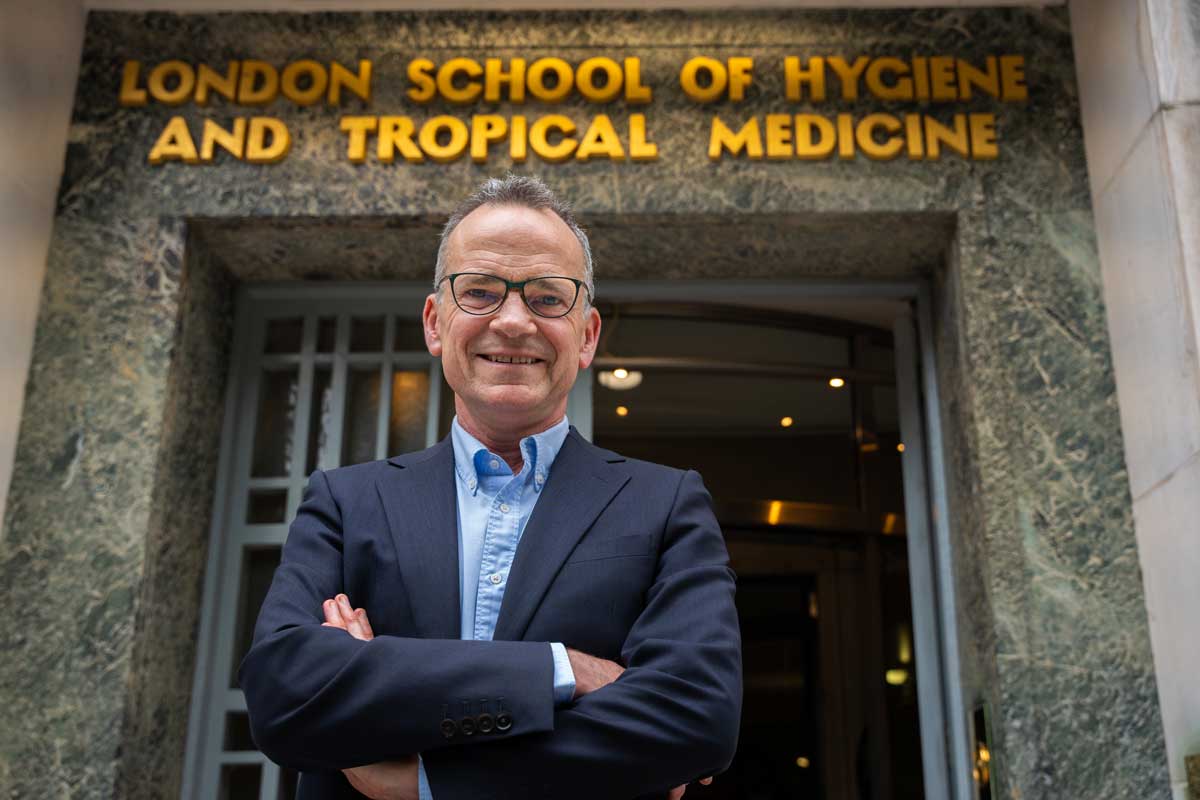

VaccinesWork spoke to Professor Liam Smeeth, Director of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, on their new key principles to inform the fight against misinformation.

- 28 February 2025

- 7 min read

- by Priya Joi

Misinformation is one of the biggest threats to our health today, with falsehoods spreading rapidly online that can so easily turn deadly.

Last month the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine’s (LSHTM’s) Director, Professor Liam Smeeth, called for 2025 to be the year that we join together to fight back, and set out six communication principles to counter the current flood of misinformation. We spoke to him to find out more.

There is research to indicate that many people spreading misinformation aren’t deliberately trying to spread fake news, but are drawn to news that aligns with what they believe to be true – it “feels true”. In an age of AI, we are all likely to be exposed to information that is hard to verify, so how do we counter this?

Well, over the past decade or so, especially in the social media era, a lot of these issues have become highly political. We saw this with COVID-19, particularly in in the USA where in some states if you were wearing a face mask you might as well have had Democratic voter written on it.

What we see is people often sharing information that plays into their existing narrative. And of course with social media, the algorithm sends people down routes that they already agree with, and they forward things on to people who already agree with them.

The problem with this is that it makes people increasingly want to believe only the things they agree with. For instance, you don’t have to love the idea of a measles vaccine – there might be lots of reasons why you don’t love the idea of measles vaccine that are to do with your political outlook or something else, but the point is that just because you don’t like the idea of it, it doesn’t mean it causes autism.

In science communication, there used to be a big focus on improving public science education 15–20 years ago, and it seems like it’s not been talked about as much lately. Could it be useful to bring that back to life?

I think it could, actually, because the public understanding of science is so crucial. In the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, the BBC was reporting the R number of the virus – the idea that the BBC would feel sufficient numbers of their audience would know what it meant was extraordinary. And I think for a while, the scientific community maybe felt it might signal a better understanding of science.

And then when vaccines were made, people were hearing about mRNA. Unfortunately, there was some misinformation that the vaccines could alter our genes. Even then, I don’t think most people who believed that or shared it were being malicious about it. I think they were genuinely concerned because it wasn’t clear to them how the vaccines worked.

The mRNA COVID-19 vaccines are a good case in point. As science communicators, you're always trying not to overload people with information. But in those instances, could we as a community have done a better job of heading off some of these questions and concerns at the start?

Yes I think [we] could. There’s a real need to communicate simply. Quite a while ago, I remember a public health campaign in the UK that said “The flu vaccine cannot give you flu, because there isn’t any flu virus in it.“

That was it, because there was this myth that the flu vaccine could you give you really bad flu. But that is scientifically, absolutely untrue. It is always worth remembering that what is obvious to scientists isn’t obvious to the general public.

At LSHTM, you published six principles for countering misinformation that read as robust and practical – how did they come about?

They came about from us as an organisation, including academics who have worked in this area and our comms department, thinking about issues and reflecting on how to respond to the threat of misinformation in a reality where budgets, time and energy are constrained.

A unifying feature of the principles is being pragmatic about what scientific organisations can achieve, especially in response to major political shifts in the world.

While there are moments when political decisions are made that directly impact public health, we do comment on those, but otherwise we try to focus on our remit, which is health and health equity, and things that impact on it. We stick to the science.

Empathy is a key principle because we don’t see the value in blaming people who spread misinformation. Most people are sharing false information out of fear or worry rather than maliciousness.

One of the LSHTM principles in fighting misinformation is to build trust. During the pandemic, some governments and organisations may have lost the public’s trust because of the way they handled the crisis and, more importantly, how they communicated about it. How do we build back trust?

Yes this is a very tough one. Many political post-pandemic analyses seemed to be a “who can we blame” enquiry rather than looking at what we can learn and how we can do better in the future. Unfortunately, some politicians did completely break the public’s trust during the pandemic.

But I think we could do with more openness and honesty in acknowledging that policy decisions, particularly when you are faced with something like a pandemic, are really difficult to make.

In many countries, the total shutdown of so many industries and the loss of so many jobs to stop the virus circulating wasn’t considered in a very balanced way I think. The impact of losing so many jobs could have huge implications.

But the need to balance different priorities – for example, controlling viral circulation versus getting the economy moving – was never explicitly shared with the public. Politicians being more open about the need for a more holistic approach would have been useful.

Have you read?

Does LSHTM have any more plans in terms of combatting misinformation?

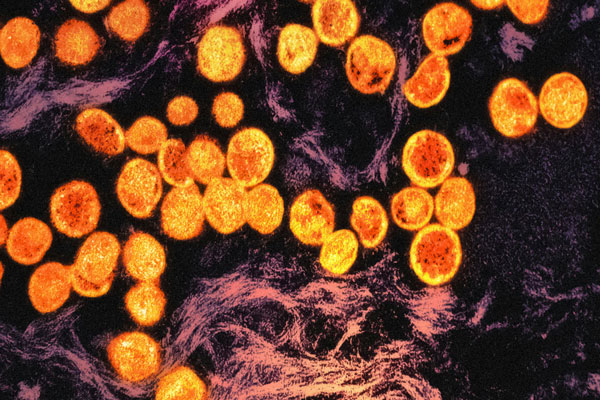

One of the first topics we are looking at is vaccine misinformation. Our communications team are currently working with experts to gather the messages, stats and examples we need to be able to respond to misinformation attacks in the media and on social media.

We are thinking about creating an informal UK network, including both academic experts and communications professionals, to share intelligence on health misinformation attacks and effective interventions. It could be very useful for the scientific community to coalesce around a few key issues that would allow us to have a big impact.

We are also developing plans for an event later this year that will focus on sharing knowledge and inspiring ideas about how to respond to health misinformation.

What about going beyond the UK to a global alliance?

Yes that would be really important. Particularly on some of the big issues, to create a coordinated approach.

One thing we have seen time and again is that it is more important to get one really crucial message across than 2,000 smaller ones. A coordinated global network could really help with this.

LSHTM’s counter-misinformation principles for communications

Decide your threshold: LSHTM cannot respond to every misinformation attack. A response to misinformation about key topics should be considered if it is both spreading widely and being shared by influential people/groups and likely to cause significant health harms or have a significant negative effect on LSHTM’s work in this area.

LSHTM has identified four key topics related to its work at high risk of misinformation attacks: pandemics, climate and health, vaccines, reproductive health/women’s health.

Choose your audience: Consider which audiences you are trying to influence. Directly targeting those generating misinformation is unlikely to work and will only fuel polarisation. Targeting the large audience of undecided ‘don’t knows’ on any issue and, for example, persuading them not to share misinformation is a more effective strategy.

Engage with empathy: Any response should recognise that people sharing misinformation may be doing so out of genuine concerns and address those concerns sensitively. Instead of tackling core beliefs head on, which is likely to provoke a negative reaction, try a neutral framing of the topic (for example: “find out more…”, “the facts about…”) with accessible facts, stats, and links to credible sources people can investigate themselves.

Quarantine the attack: Only ever repeat a misinformation attack in a weakened form, otherwise you risk spreading the very misinformation you are trying to contain. If you are giving details of false claims always surround a weakened version of the misinformation with facts, strong counter-arguments, and links to credible sources.

Demonstrate consensus: People’s understanding of complex science is closely linked to their perception of whether or not there is scientific consensus on an issue, so wherever possible provide evidence of consensus.

Build trust: Earn the trust of your audience by ‘showing your working’ at every turn and explaining the evidence clearly, accessibly, and honestly, including areas where there are real problems or uncertainties.

More from Priya Joi

Recommended for you