Uzbekistan steps up its fight against drug-resistant tuberculosis

Shorter, easier-to-complete treatment protocols and better diagnostics promise change, but fear and stigma imperil progress in one of Europe’s most TB-burdened countries.

- 9 August 2023

- 6 min read

- by Umida Maniyazova

Khaliknazar, a 64-year-old man from Namangan city, has spent most of the past four years in and out of treatment for drug-resistant tuberculosis – a growing threat in Uzbekistan and around the world.

“At first I was treated at the dispensary. Within a month and a half my condition improved significantly. Every day we took analyses and monitored the changes. After that, I had to take medicines for another four months,” he said.

Five months after that treatment course ended, he suddenly started coughing again. “My son got worried and took me for a check-up. What he had feared had happened. The TB bacilli reappeared in my lungs.”

Five months after his treatment for drug-resistant TB ended, 64-year-old Khaliknazar started coughing again. “My son got worried and took me for a check-up. What he feared had happened. The TB bacilli reappeared in my lungs.”

Khaliknazar was treated again as an outpatient for two months, and took medicine at home for a further two years. “Fortunately, nothing has bothered me since then,” he said. “I have learned one thing: even if your condition is good, you need to take the prescribed medicines on time.”

About 1.6 million people globally die of tuberculosis each year, and the threat from the ancient bacterium is only growing as drug resistant forms of the infection rise worldwide. An estimated 3.6% of TB cases proved multidrug resistant (MDR-TB) or resistant to rifampicin (RR-TB), one of the most powerful anti-TB medicines, in 2021. 18% of cases in 2021 qualified as “previously treated”, suggesting relapse.

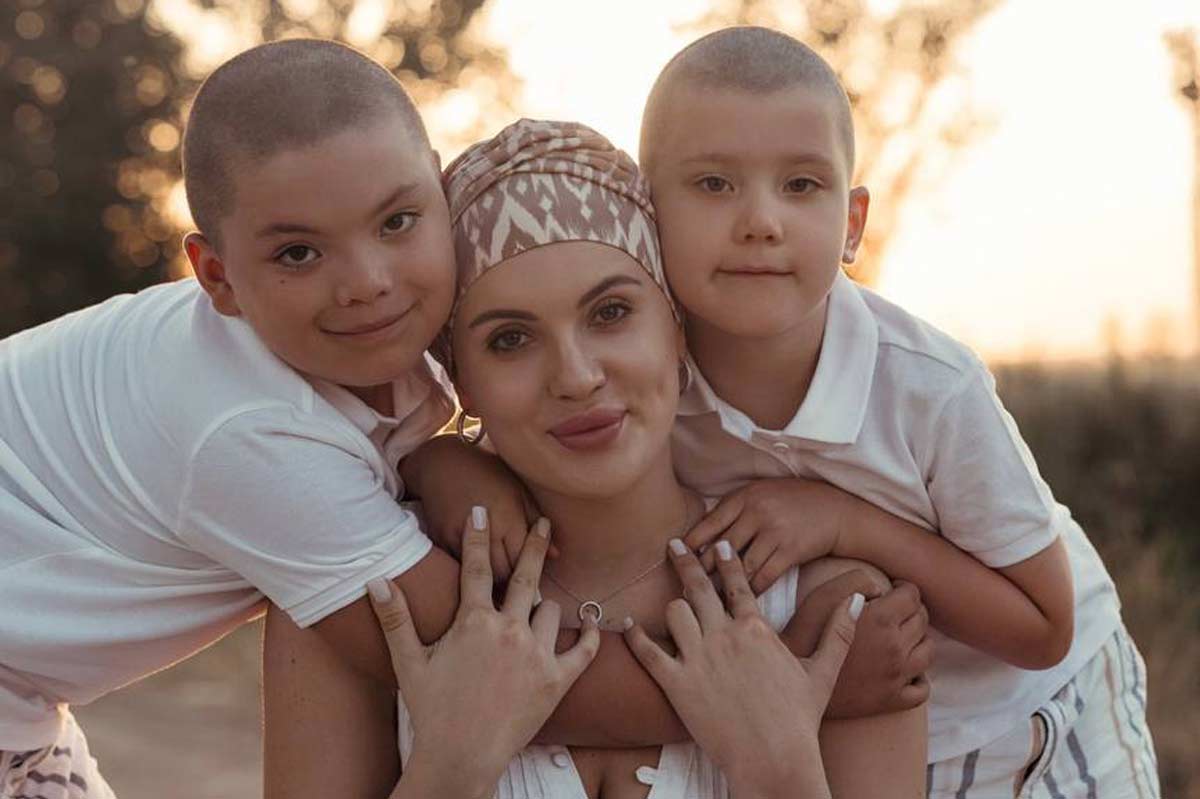

Credit: Ministry of Health of Uzbekistan

Uzbekistan has one of the five highest TB rates in the European region, with an estimated 62 cases of pulmonary TB per 100,000 people in 2021, and has one of the 30 highest MDR and RR-TB rates globally.

Shorter treatment protocols

But promising new treatments are offering patients like Khaliknazar some hope of an easier – and shorter – pathway back to health.

In December 2022, the New England Journal of Medicine published a study, based on research conducted in Uzbekistan, Belarus and South Africa, which showed that a 24-week, all-oral regimen of bedaquiline, pretomanid, linezolid and moxifloxacin (BPaLM), was “noninferior” to the 9-to-20 month standard protocol for rifampicin-resistant TB. The new treatment also had a better safety profile.

Have you read?

With the support of Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), which also supported the TB-PRACTECAL clinical trials that produced in the NEJM paper, five countries have now introduced short-term treatment schemes, and almost 400 patients have been admitted to the new treatment process. Eight more countries intend to introduce the new schemes in 2023.

“The recovery period has shortened from two years to nine months,” she added. “Currently, our scientists are conducting research to shorten the course of treatment for TB patients by another six months.”

– Nargiza Parpiyeva, Director of the Republican Specialised Scientific and Practical Medical Centre for Phthisiology and Pulmonology

Uzbekistan is currently operating a mix of protocols, explained Bakhtiyar Babamuradov, Country Director/TB adviser with Abt Associates to USAID’s Eliminating TB in Central Asia programme. “In Uzbekistan, new treatment regimes are used (non-injection, only tablets), but short-term regimens using bedaquiline are used within the territories where operational research is being carried out,” he said.

“According to WHO, the effectiveness of TB treatment in Uzbekistan in 2021 was 91% for cases with drug-susceptible forms, and 70% for cases with multidrug-resistant forms of TB,” he added.

Quicker diagnostics

Prevention – by vaccination with the BCG vaccine soon after birth, and by screening – is a vital pillar in Uzbekistan’s TB strategy. “It used to take three to four months to diagnose tuberculosis,” said Professor Nargiza Parpiyeva, director of the Republican Specialised Scientific and Practical Medical Centre for Phthisiology and Pulmonology. “As a result of the introduction of new diagnostic and treatment methods in medicine, today the disease is accurately diagnosed using genomolecular methods in the shortest possible time.”

“The recovery period has shortened from two years to nine months,” she added. “Currently, our scientists are conducting research to shorten the course of treatment for TB patients by another six months.”

A lonely road

But TB patients know that outcomes still depend, among other things, on how early the illness was diagnosed, and how well the patient follows his or her doctor’s instructions.

That’s not necessarily easy to do. Though TB treatment is free in Uzbekistan, TB therapy typically takes many months and often requires isolation from society in a TB dispensary, and comes with other major changes to a patient’s lifestyle.

"Of course, taking five or six tablets every day is hard for a person. It even comes with nausea. But one thing is clear: a person who is being treated for tuberculosis will not recover without medication."

One survivor, a 59-year-old man who declined to be named, recalled, “I thought the TB dispensary was a very closed area. And so, at first, I asked the doctors to treat me at home. But when they explained to me that I would endanger my loved ones, I reconciled.

“Seeing how [much] thinner people [in treatment became], I was worried I would become like them. My heart sank at the thought that I would lie here for three months. Over time, I got used to it, and my opinion changed,” he recounted.

His experience in the TB clinic also offered insights into one driver of antimicrobial resistance: non-adherence to the prescribed treatment course. Treatment at the dispensary was oral, without injections, he shared – but still, patients dodged doses. “No matter how hard the doctors tried to explain to them the importance of the medicine, many did not take it, took it for two days, and skipped the remaining three days. Of course, taking five or six tablets every day is hard for a person. It even comes with nausea. But one thing is clear: a person who is being treated for tuberculosis will not recover without medication,” the man said.

Fighting stigma to fight TB, and antimicrobial resistance

Dropping out of treatment raises the risk not only of relapse, but also of antimicrobial resistance. Keeping patients in treatment is partly a social battle: fear and stigma make staying the treatment course more difficult for patients.

Reflected Khaliknazar, “Tuberculosis is not as incurable as I thought. Only the name of the disease is not good – once people hear it, they will start shunning you. That’s why I keep the disease a secret from everyone. I am afraid that my children and grandchildren will face discrimination.”

Secrecy and social anxiety can hinder early detection. Some people with possible symptoms of TB, like coughing, night sweats and weight loss, may not realise – or may not want to realise – that they need to see a doctor to get tested.

Uzbekistan’s Ministry of Health, together with the American non-governmental organisation Project HOPE, is combating the fear and stigma around TB by creating teams of recovered TB patients and women activists to bust through the silence, disseminate accurate information about the infection, and peddle free testing.