We can make impact bonds work harder and better to create healthcare gains for poor communities

Financing health care is not just a question of how much, but also of how. Impact bonds have done a lot to facilitate transformative change already – and our analysis suggests that they can do much more.

- 17 June 2022

- 8 min read

- by Jelena Madir , Patricia Sulser

Two and a half years into the pandemic, it’s clearer than it has been for a generation: finding the means of paying to shore up health care systems for the world’s poorest communities is an urgent, growing concern.

Need meets opportunity

Despite gradual improvements in poverty rates worldwide over the past quarter century, many lower income countries simply don’t have large enough budgets or tax bases to pay for the health services that their most vulnerable citizens need. The market rarely steps in: health care for the poorest and most marginalised has historically been one of the least attractive social sectors for private sector investment. So health care provision remains, in many cases, up to development agencies, charities and other donor organisations.

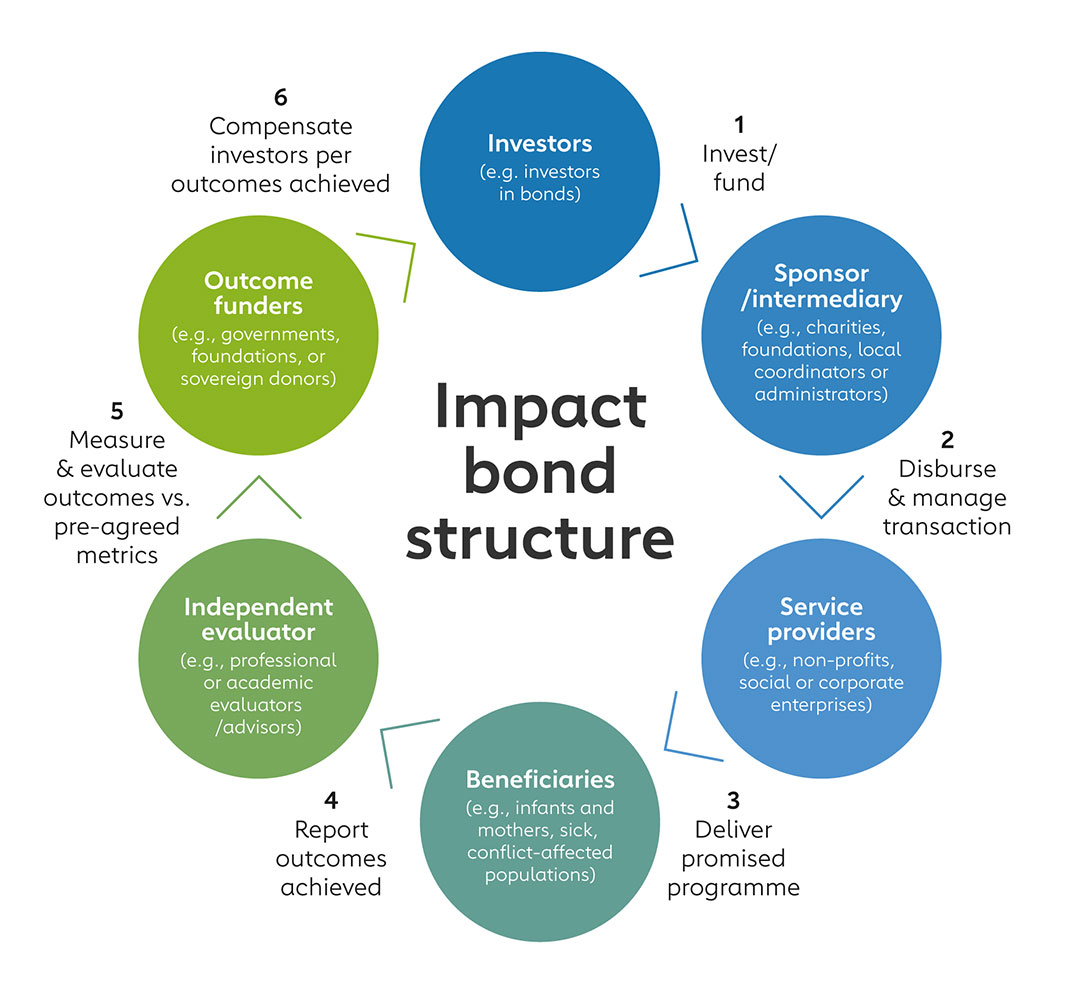

An impact bond works like this: private investors put up the money for a programme or project, which is undertaken by an intermediary who promises to deliver pre-agreed outcomes on the ground. If these outcomes are achieved and validated, the “outcome funder” – usually a host government, sometimes a sponsoring charity or philanthropic body – commits to repay the investors’ investment, along with a return, on an agreed date.

The bad news: amid climate change, looming infectious disease threats, and a ballooning global population, the need is only increasing. Paying for big changes in public health is expensive. More, many crucial undertakings – building a hospital, for instance, or rolling out a new life-saving vaccine – demand great sums of money upfront, which can be a complicated ask when so much donor funding works on an annual budget cycle.

The good news: in the past 20 years, we’ve gotten cleverer at funding development programmes of all kinds. Results-based grant funding, which adopts an approach from schemes previously more typical in commercial contexts, has offered donors the opportunity to better ensure the value of their investment.

Public-private partnerships (PPPs) have brought private capital into the development space, and shuffled some risk onto private investors, with tremendous positive impacts on public health in low-income settings. Gavi and the Global Fund, to name two prominent examples, have leveraged the potential of PPPs to protect the health of hundreds of millions of people in the last two decades.

The community of impact investors – who demand both sustainable development and financial payoffs – has grown, and a variety of innovative, ad hoc “blended finance” approaches have sprung up. But these have often been easier to mobilise for revenue-generating initiatives. To draw private sector investors to initiatives that are usually non-revenue generating, development organisations including Gavi have tested out different models of impact bonds. These vary widely in structure, but generally leverage upfront private investment to operationalise development programmes, backed by slower-to-land “outcome funder” cash.

Case study: Gavi and IFFIm

Manufacturing and distributing millions of vaccines costs a lot of money, upfront. Relying on annual, smaller government and donor funding constrains both reach and efficiency. Instead, Gavi, through a UK-based charity called the International Finance Facility for Immunisation (IFFIm), has issued public vaccine bonds which have drawn US $7.5 billion in investment from both institutional and retail markets since 2006.

Here’s how IFFIm bonds help Gavi make a massive impact on global health: Consider a donor government that pledges US $100 million to Gavi, paid in $10 million tranches annually over a decade. Based on that arrangement, Gavi is limited to spending only $10 million a year, and has to wait 10 years before seeing the full impact of pledged funds. Instead, backed by this donor pledge of $100 million, IFFIm steps in and issues its vaccine bonds in international capital markets. Investors buy these bonds for an attractive rate of return, making funds immediately available to IFFIm. Gavi then uses the proceeds of the bond issuances to buy more vaccines, and immunise more people in the world’s poorest countries. The donor governments’ annual payments ($10 million) go towards repayment of the bondholders over several years.

This brings us to the even-better news. In our new paper, we examine the different types of social and development impact bonds available and find that there’s enormous opportunity here. Impact bonds have the potential to help us dramatically scale up the funding and delivery of health care services in developing countries, making more funds available on a more opportune timeline, and spreading risk among different stakeholders.

Have you read?

But what is an impact bond?

Because impact bonds have mostly been constructed as ad hoc, bespoke instruments, they take many forms (many of them haven’t even truly been bond instruments, but customized, privately-negotiated bilateral pay-for-performance arrangements).

But at root, an impact bond works like this: private investors put up the money for a programme or project, which is undertaken by an intermediary who promises to deliver pre-agreed social (or health) outcomes on the ground. If these outcomes are achieved and validated, the “outcome funder” – usually a host government, sometimes a sponsoring charity or philanthropic body – commits to repay the investors’ investment, along with a return, on an agreed date (or schedule).

Because the outcomes are specified as a condition for repayment (of the capital or of the return), risk can be shared out among the investor, the intermediary and the outcome funder in various ways. And crucially, a programme that would otherwise only have been paid for in small chunks, can be paid for upfront – enabling better planning and delivery.

Case study: The Cameroon Cataract Bond

The point of impact bonds is to relieve governments and sponsoring organisations from heavy upfront funding of big social or development programmes. Here’s how that is working in the case of the Cameroon Cataract Development Impact Bond, which aims to enable the provision of low or no-cost cataract surgery for up to 18,000 people.

Drawing investors including the US Development Finance Corporation and the Netri Foundation, the bond gives the service provider, the Magrabi ICO Cameroon Eye Institute, the money it needs to work towards a pre-agreed set of outcomes, including certain financial outcomes. If those goals are met in time, outcome funders – who include the Conrad N Hilton Foundation, the Fred Hollows Foundation and Sightsavers – are required to repay investors their initial investment plus a pre-negotiated return. Investors only risk losing their return if the goals are not met – repayment of the initial capital is guaranteed.

How do we make impact bonds work harder, better?

Impact bonds are not a panacea: they will not be the right mechanism to free up funds for every big development programme. But there is tremendous untapped potential here. So, how do we make impact bonds better at doing good work?

Standardisation would mark a vital first step. Generating a single basic impact bond structure – plus streamlined documentation and a uniform terminology – rather than constructing bespoke, ad-hoc, bilateral instruments in every case, would turn impact bonds into a readier, more scalable tool, and one more likely to attract a wider range of risk-taking investors and outcome funders. These bonds will also need to have the features that private commercial investors expect of corporate or sovereign bonds, including credit quality, competitive returns and liquidity, which can be achieved with careful planning and the right players at the table.

There’s also a question of communication. Impact bond-funded projects don’t only bear fruit for their direct beneficiaries – there are ripples and knock-ons that can be identified valuably. We need to articulate the narrative beyond the pre-agreed outcomes specified in the contractual documentation. If an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure, let’s explain why. Better still, let’s quantify it. A wider narrative is likely to identify a wider range of stakeholders as investors or high-quality outcome funders.

We also need to spell out the value-for-money proposition for both investors and citizens. At first blush, bringing in the private sector might seem to make deliverables more expensive. But a rigorous qualitative and quantitative and, importantly, publicly available value-for-money analysis needs to be able to clearly demonstrate that the bond-backed programme is worth the investment of public money.

And still, we need to share the risks out between the service providers, the government or charities backing the work, and the investors. Encouraging commercial investors to take on risk (as they might in a commercial investment) for benefits that they derive and value –whether financial, health, or other social or developmental – is reasonable. Some investors might still need certain capital protections in exchange for such risk and their pricing, which can take a range of forms – offering interim repayments against key milestones is one example.

Finally we need a regulated impact bond marketplace where governments, international and aid organisations, NGOs, charities and philanthropies can find investors and outcome funders by sector, country and area of interest. Crowding in private sector commercial investors could unlock authentically transformative capital for the delivery of health care in poor countries.