What is vaccine-derived polio?

Before the introduction of vaccines, polio killed or paralysed more than half a million people worldwide every year. Since the late 1980s, cases have fallen by 99.9%, due to global efforts to immunise children with the oral polio vaccine. However, in communities with low vaccination coverage, the weakened polioviruses in this type of vaccine can – in rare cases – undergo changes that can threaten people’s health.

- 28 July 2022

- 4 min read

- by Linda Geddes

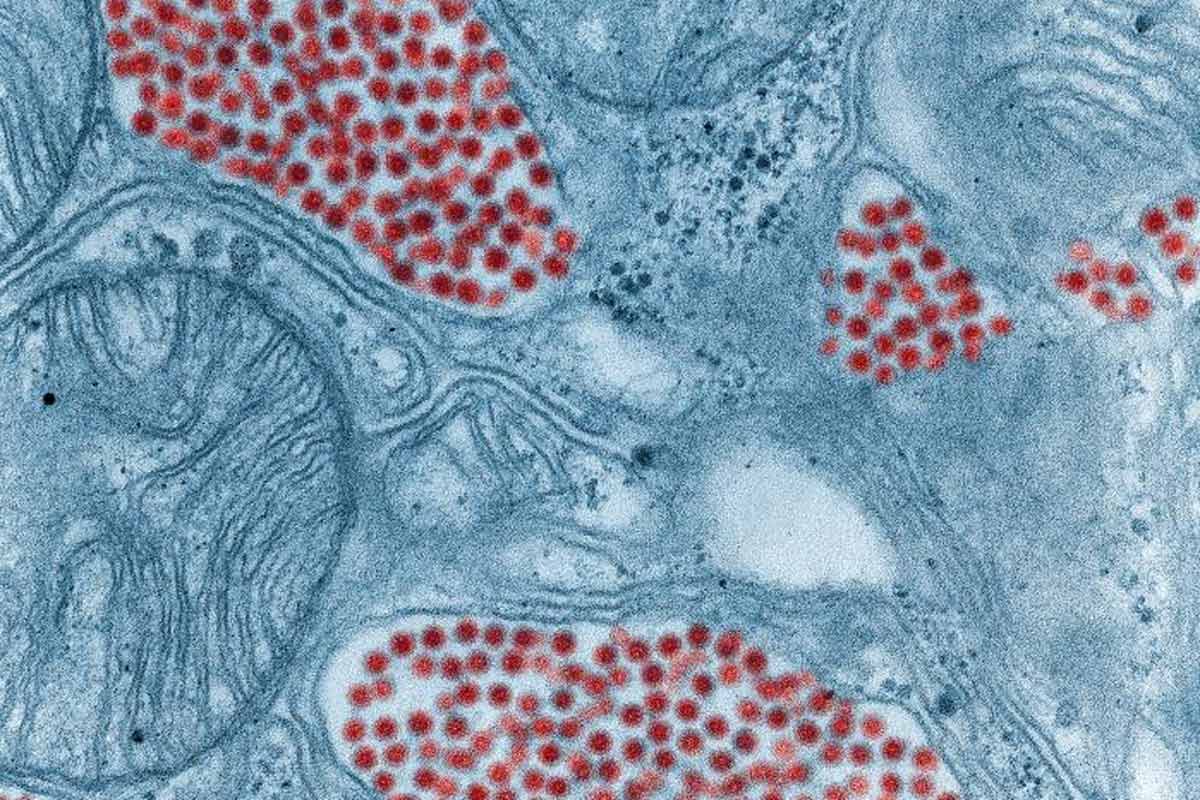

Polio spreads from person to person through contact with faeces, often as a result of poor hand hygiene or consuming food or water contaminated with human faeces. The virus initially replicates in the nose or throat, before moving to the intestines and multiplying, then entering the bloodstream and invading the central nervous system, where it can cause nerve damage and paralysis. Around one in 200 people who contract the disease will suffer paralysis; between five and ten percent of people who develop paralysis die because their breathing muscles stop working.

Vaccine-derived polio is extremely rare. Since 2000, more than 10 billion doses of OPV have been given to nearly three billion children worldwide, and just over 1,000 cases of vaccine-derived polio paralysis have been reported during that period.

Fortunately, vaccines are highly effective at preventing polio. There are two types: The first is oral polio vaccine (OPV). It contains a mixture of poliovirus strains that have been weakened, meaning they can still replicate, but are not strong enough to cause paralysis. Because OPV is given via the mouth, it triggers the production of antibodies in both the intestines and the blood. This means that if a vaccinated person is exposed to wild poliovirus in the future, the virus won’t be able to replicate and infect other people.

The other type of vaccine is inactivated polio vaccine (IPV). It is produced from polioviruses that have been killed, so they cannot replicate, and is injected into the leg or arm. Although it is very good at triggering antibodies in the blood, preventing the virus from travelling to the nerves and causing paralysis, IPV is less effective at triggering antibodies in the intestines. This means that vaccinated people can still become infected with wild poliovirus and transmit it to other people, even though they don’t become ill themselves.

Historically, OPV has been more popular than IPV because it is cheaper and easier to administer, allowing large numbers of children to be vaccinated. It also protects both the individual and the community against infection – unlike IPV, which only protects the individual – which is important if poliovirus is to be eradicated.

Have you read?

Importantly though, because OPV contains weakened viruses that can replicate, some of them may be excreted by the vaccinated child and transmitted to other people – particularly in areas with poor sanitation. This can be beneficial because exposure to this weakened virus also immunises these individuals against polio.

However, too much transmission of this weakened virus can be problematic. In communities where lots of people have been vaccinated against polio, onward transmission is limited, and the virus quickly dies out. But in communities with low vaccine coverage, this weakened virus may continue to circulate for many months, gradually accumulating mutations that enable it to cause paralysis once more.

Vaccine-derived polio is extremely rare. Since 2000, more than 10 billion doses of OPV have been given to nearly three billion children worldwide, and just over 1,000 cases of vaccine-derived polio paralysis have been reported during that period.

It also only emerges in under-immunised communities, which is one reason why vaccinating every child is so important: If communities are fully immunised, this helps prevent the spread of both wild and vaccine-derived polio.

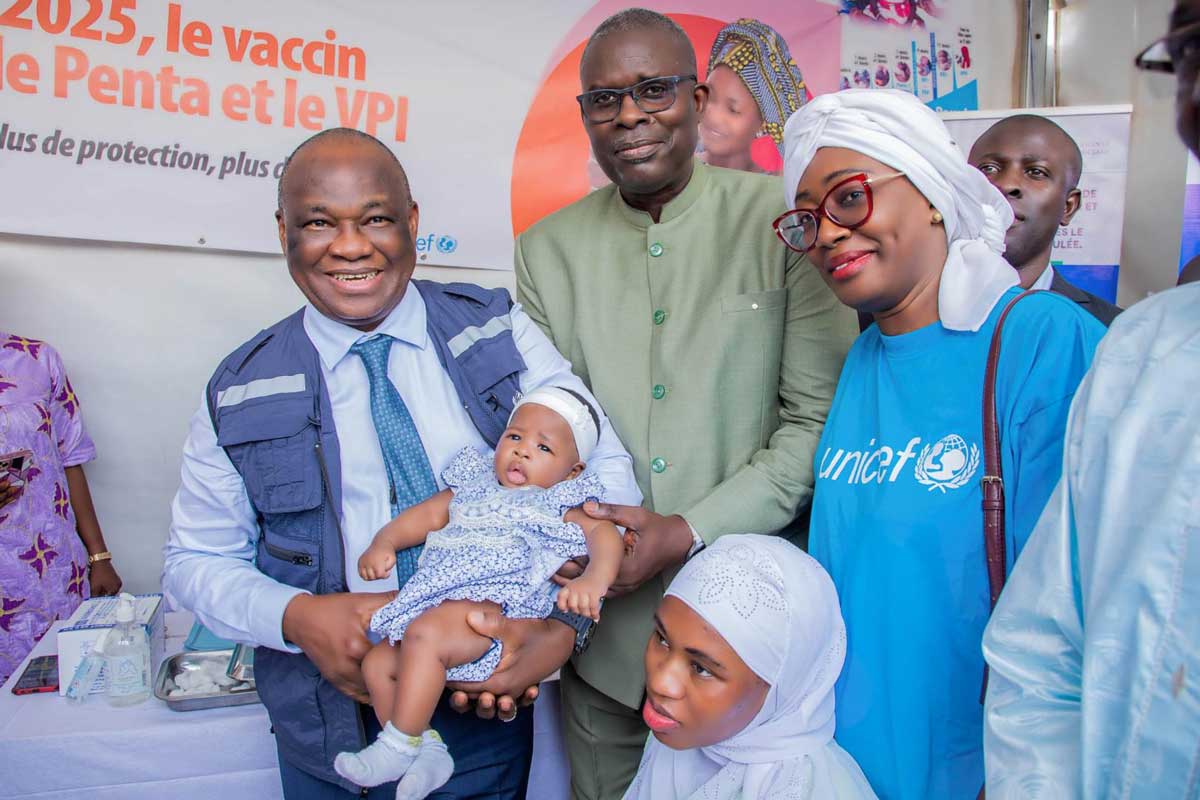

A novel OPV has also been developed that should provide the same protection as the current oral vaccine, with less risk of mutating and causing paralysis. It is currently being used to tackle outbreaks of vaccine-derived poliovirus in a small number of countries.

Huge progress has been made in the fight against polio, but high uptake of polio vaccine will be necessary to eradicate polio for good.