Yellow Fever and the Panama Canal

At the turn of the 20th Century, US researchers in Cuba made the historic discovery that mosquitoes spread yellow fever. The finding was not only a medical breakthrough; it would also make possible one of the world’s greatest feats of engineering.

- 27 May 2021

- 6 min read

- by Maya Prabhu

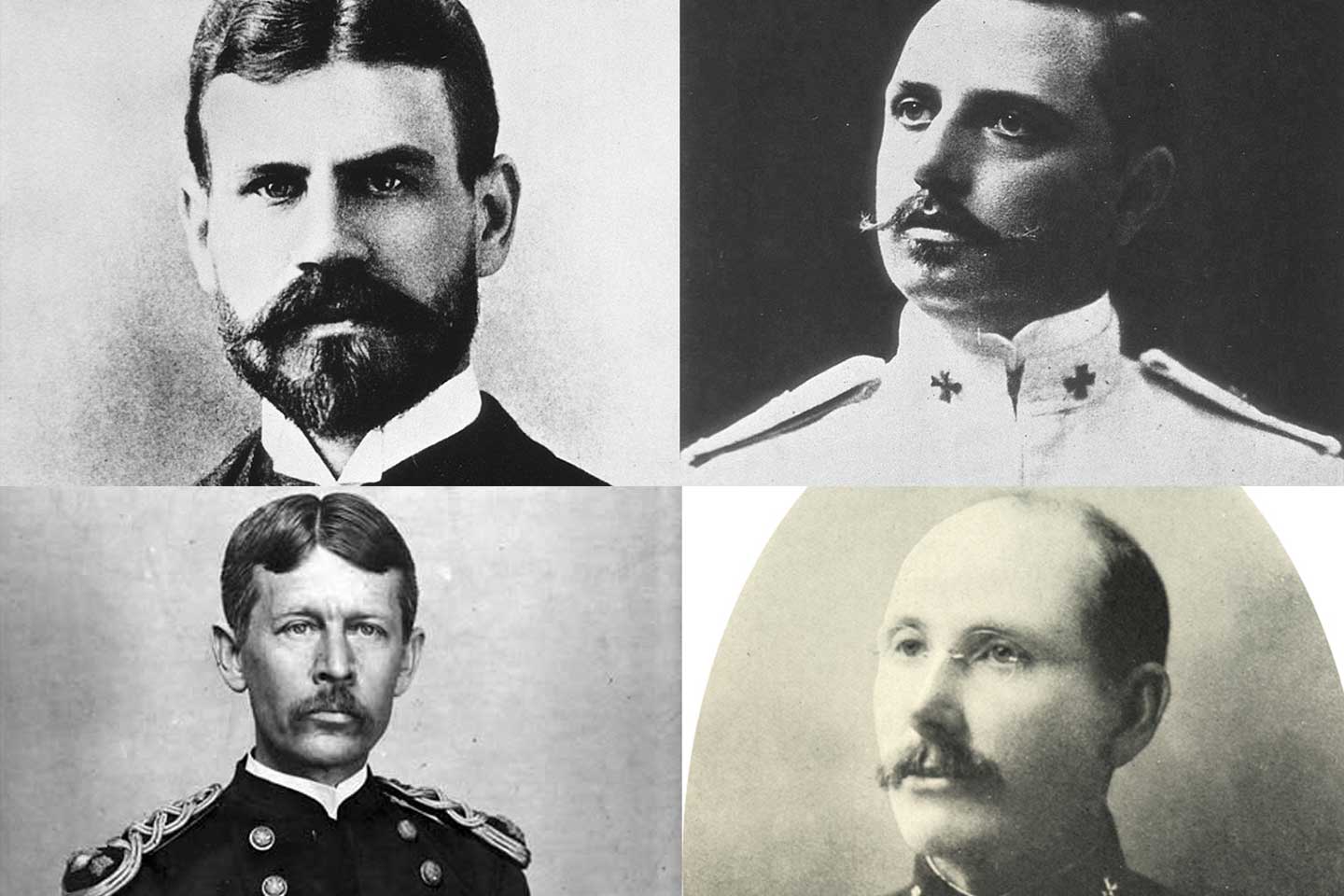

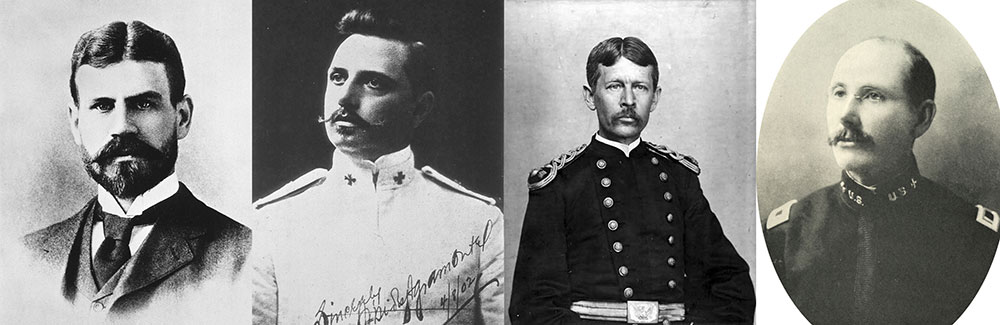

Dr Jesse Lazear was wrangling mosquitoes – herding one out of the mouth of a test tube and down the neck of another – when the man who would become his breakthrough experimental subject strolled up and saluted. This was the sun-flushed morning of August 31, 1900, and Lazear and his colleague Dr Aristides Agramonte, two of the four medical officers who made up the U.S. Army Yellow Fever Commission, were working out of a makeshift laboratory in an American military encampment in Cuba. The young soldier in the doorway was Private William H Dean of the Seventh Cavalry. “You still fooling with mosquitoes, Doctor?” Dean asked. “Yes,” said Lazear, according to Agramonte’s recollections. “Will you take a bite?”

Dean, all soldierly swagger, agreed – “Sure I ain’t scared of ‘em” – and pushed back his shirtsleeve. The doctor nudged the opening of a test tube up against the bare skin of Dean’s forearm, and watched as the mosquito trapped inside descended to feed.

Within five days, Dean was sick. It was a landmark result for a radical, risky campaign of medical experimentation: Dean became, in Agramonte’s words, “the first indubitable case of yellow fever… to be produced experimentally by the bite of purposely infected mosquitoes.”

Until that moment the notion that mosquitoes were responsible for spreading the killer sickness that was currently tearing through Havana had been dismissed by most respected specialists. Dr Carlos Finlay, the Cuban doctor who had been the mosquito theory’s biggest champion for twenty years, had never managed to muster conclusive proof and had haemorrhaged credibility among his fellows. But from the perspective of US leadership, the need to get a handle on yellow fever’s aetiology had never been more urgent.

If the devastation of Philadelphia’s 1793 outbreak was shrinking into the past, the memory of 20,000 yellow fever deaths in the lower Mississippi valley in 1878 remained fresh. Even more pressing was the painful knowledge that during the Spanish-American war of 1898, which resulted in the US occupation of Cuba, more than four times as many American soldiers died of yellow fever than fell in combat. Meanwhile, America had been eyeing up the strategically attractive, logistically nightmarish French dig-site that was to become the Panama Canal – aware, no doubt, that part of the reason the French project had failed was that its engineers and labourers were dying in droves because of the disease.

Have you read?

Knowing how the sickness is transmitted was key to halting its spread. The four-man Commission arrived in Cuba in June 1900, determined to puzzle it out. They noticed that conventional epidemic measures, like overhauling Havana’s sanitation systems, helped control other illnesses but did nothing against yellow fever. They learned of strange patterns of infection: transmission appearing to occur at distance, and across time, but not occurring at close quarters. Agramonte recorded with curiosity the case of a soldier-prisoner who bunked with a yellow-fever afflicted inmate but never fell sick. A live vector seemed to fit.

Carlos Finlay furnished them with an arsenal of mosquito eggs and hypotheses. Lazear, who had experience with malaria and knew his way around the insects, took charge of mosquito management. But after more than two months of apparently fruitless experimentation – mosquito after mosquito fed on the blood of hospitalised yellow fever patients, each meticulously labelled and logged before being exposed again to the healthy and un-immune – even Lazear wasn’t quite convinced that the mosquito vector theory held up.

Then, in August, Dr James Carroll – who, like his Commission colleagues, had volunteered his own arms to the mosquitoes – got sick. But since Carroll had been working in a yellow fever hospital, and was therefore exposed in multiple ways, the researchers needed a more perfect test-subject. Enter Private Dean, new to Cuba and willing to chance it.

The danger was grave: even in the 21st century, the unvaccinated face a 20-50 percent risk of death if they contract a severe case of yellow fever. For Lazear, Agramonte and the Commission leader, Dr Walter Reed, the triumph of discovery was therefore tempered by anxiety. Would Dean, whom they'd deliberately sickened, succumb to the disease? Would Carroll, their friend and team-mate, pull through? “Lazear and I were well-nigh on the verge of distraction,” wrote Agramonte.

Weeks later, it was thirty-four year old Lazear, not Dean or Carroll, who had gone. The agent of his disease, thought Agramonte, was a wild mosquito that bit him as he held a mosquito in a test tube to the abdomen of a patient at Las Animas Hospital. When the Commission published their ground-breaking preliminary results that year, a footnote succeeded Lazear’s name: “Died of yellow fever at Columbia Barracks, Cuba, Sept. 25, 1900.”

The experiment entered its second phase – more data was required to conclusively prove the preliminary findings. Test subjects signed stoical waivers. “The undersigned understands perfectly well that in case of the development of yellow fever in him, that he endangers his life to a certain extent, but it being entirely impossible for him to avoid infection during his stay in this island, he prefers to take the chance of contracting it intentionally…”, wrote one.

But within just months of Lazear’s death, and as a direct result of the Commission’s high-stakes research, the threat of catching yellow fever in Cuba had diminished to practically nothing. In 1901, Major William Gorgas, Havana’s Chief Sanitary Officer, launched a massive vector control offensive: homes were inspected, water receptacles – which risked becoming mosquito breeding grounds – were mosquito-proofed, drinking water was chemically treated, and pyrethrum powder was burned to knock out the adult insects. The number of yellow fever deaths in Havana, normally averaging 462 deaths per year, dropped to tens of fatalities in 1901. By January 1903, Gorgas reported to the US Senate that Cuba was now yellow fever-free.

A year later, when the US took over the French infrastructure and equipment at the Panama Canal site, Gorgas was sent in to clean up. By then, tens of thousands of workers had died on the site; an estimated 85% fell ill. In early 1905, hundreds of American labourers fled in fear of the disease. Gorgas’ detachment of 4,000 mosquito-fighters got to work. As Agramonte wrote, ten years later, “the work of prevention [is] the only one that may be considered effective when dealing with the epidemic diseases.” By December 1905, the workers stopped dying; construction could continue. In 1914, the Panama Canal opened, and a new link between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans was created.