How Yellow Fever decimated the USA’s first capital

In 1793, with the United States of America less than 20 years old, a yellow fever epidemic decimates the capital city, Philadelphia, and shines a spotlight on stark racial and social inequalities.

- 21 May 2021

- 5 min read

- by Maya Prabhu

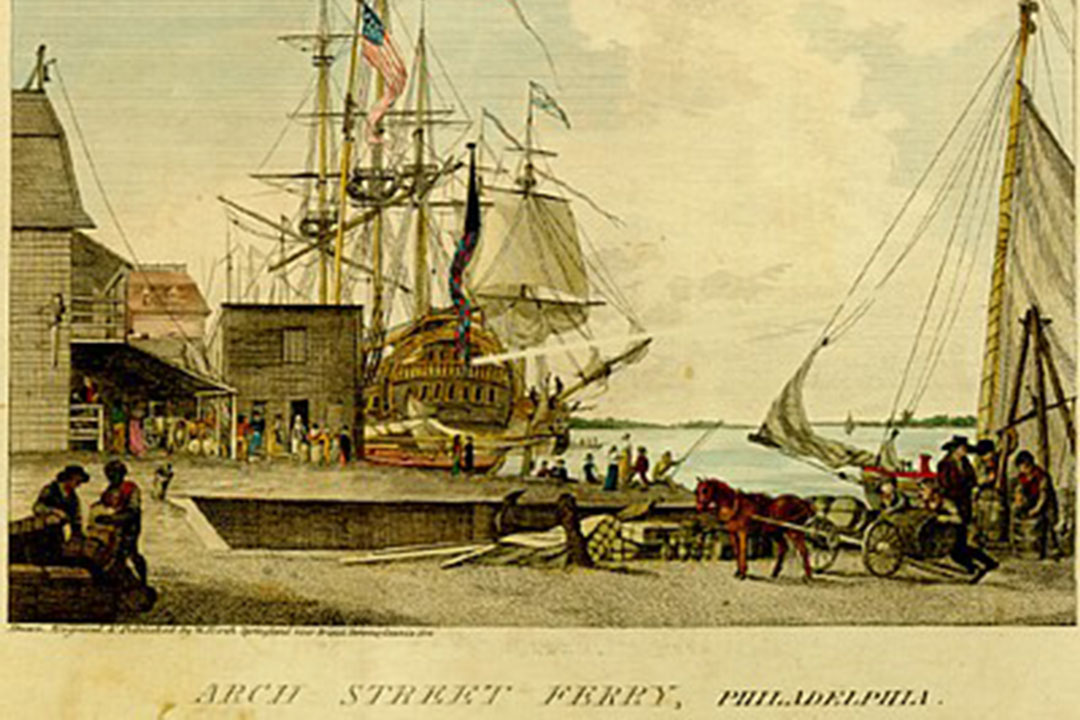

The summer of 1793 in Philadelphia is hot – currents of humidity shimmer in the air, the city stinks. Its sewage systems are poor, its tanneries and distilleries tip toxic effluent into the waterways, bloated animal carcasses lie on the river bank and, on top of that, this particular summer, a shipload of spoiled coffee is rotting on the wharf. People slap mosquitoes. Soon, they catch fevers.

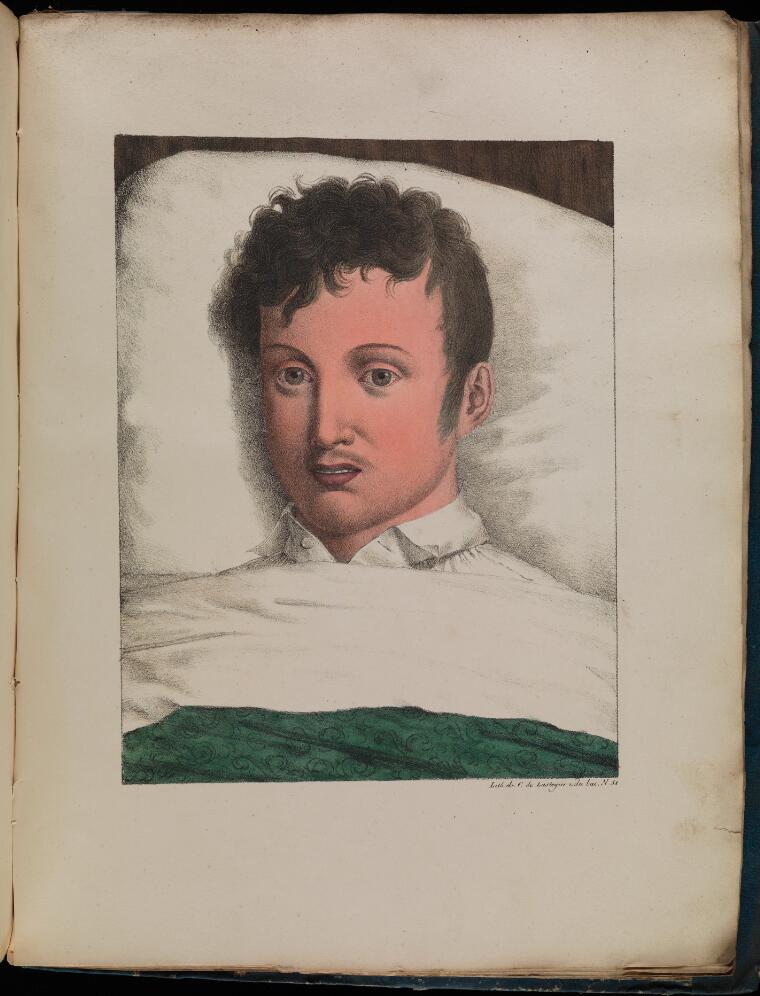

To the city’s leading physician, Dr Benjamin Rush, the mosquitoes, like the stench, seem part of a sort of generalised atmospheric sickness, a 'miasma'. It’s the miasma, he thinks, that is seeding the “bilious remitting yellow fevers” he sees that August, beginning in the city’s poorer districts on the edge of the Delaware river. As the disease deepens, he notes, his patients develop “a yellow skin, and a black vomitting.” At month’s end, he estimates that 325 people have died – a sizeable dent in a town of 50,000, but only a taste of what’s to come.

Epidemics have a habit of exacerbating social and economic inequality. Among the Philadelphians left behind to weather the outbreak are a community of around 2,100 free, but largely poor, black men and women.

Rush does what he can with the information he has. For the afflicted, he prescribes increasingly aggressive regimes of blood-letting and mercurous chloride, hoping to restore balance to the ‘humors’ of the body. For the sake of the city at large, he sounds the alarm. He rallies Mayor Clarkson, who, in turn, calls on the College of Physicians to draw up a slate of public health guidelines. Limit interaction with the infected, they urge in a report of August 26, mark the doors of their houses. Clean the streets, the wharves, the sick-rooms. Burn gunpowder to purify the air, breathe through handkerchiefs impregnated with vinegar and camphor.

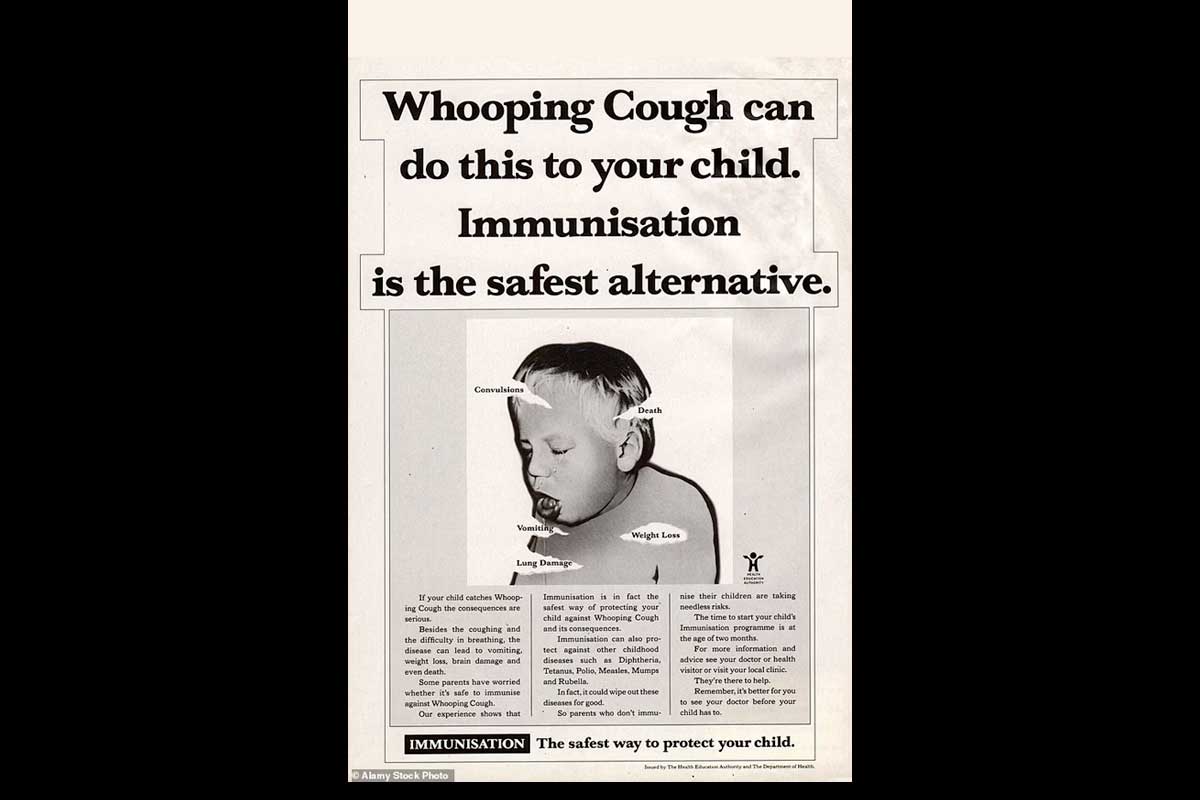

Meanwhile, the mosquitoes – which likely arrived as stowaways aboard a refugee ship from Saint Domingue, or Haiti, where the slave revolution led by Toussaint Louverture is underway – breed unchecked. But conclusive evidence that the mosquitoes are, in fact, the agents of yellow fever infection lies a century in the future. Prevention, scientists will one day understand, is the best medicine against a haemorrhagic viral disease which, even in the 21st century, kills as many as 50% of the severely afflicted. But the first good vaccine will not be discovered until 1937. Desperate Philadelphians must hope for an early winter, or run.

|

|

|

|

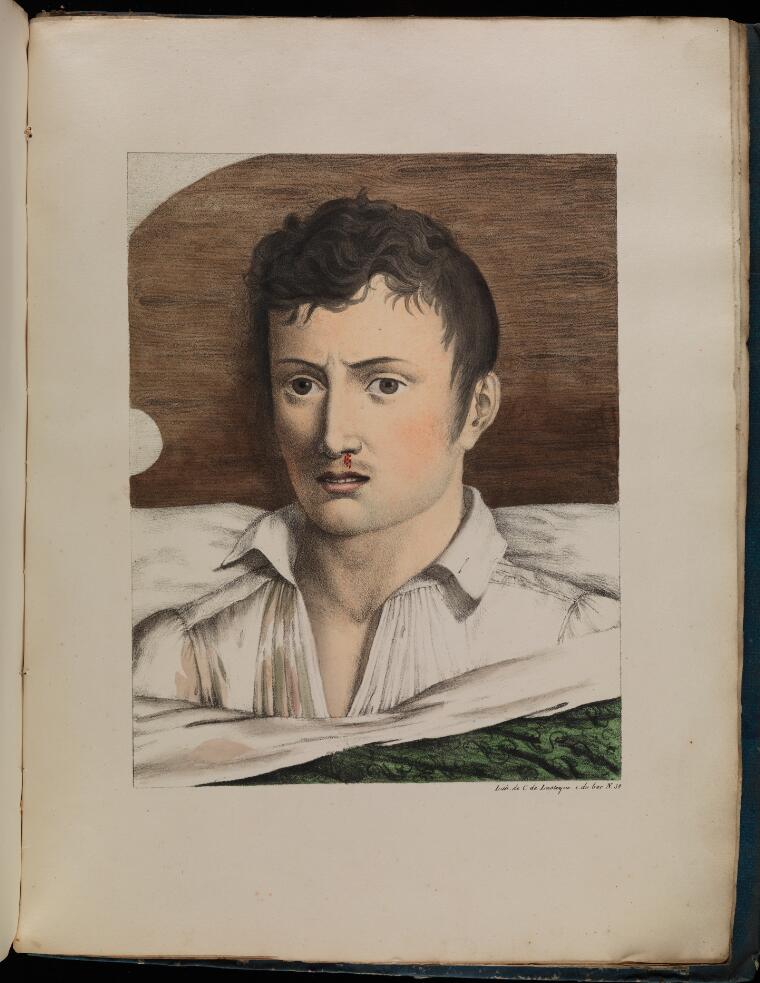

Credit: Observations sur la fièvre jaune, faites à Cadix, en 1819 / par MM. Pariset et Mazet ... et rédigées par M. Pariset.. – Wellcome Collection. Public Domain Mark

Soon 20,000 of Philadelphia’s citizens – the wealthier ones, with the means to leave – have fled. President George Washington takes to his Mount Vernon estate; Alexander Hamilton catches the infection, recovers, then whisks his family away to their summer home. Later, in November, when the first frosts of winter kill off the mosquitoes, and the epidemic’s body-count is reckoned to total 5,000, departure may seem to have been the wise choice. But in the meantime, the exodus of the city’s leadership causes havoc. Within about a week of the governor of Pennsylvania’s departure on September 6, civic order and the economy are in a state of collapse.

Have you read?

Epidemics have a habit of exacerbating social and economic inequality. Among the Philadelphians left behind to weather the outbreak are a community of around 2,100 free, but largely poor, black men and women. Rush, who has sent his family away but stayed on himself, finds a decades-old article which asserts that black people are immune to yellow fever on grounds of biological difference. It smacks of slavers’ logic – but Rush, an abolitionist, believes it. By this time, Rush writes to his wife, the city is so panicked and overwhelmed that parents abandon their children at the first symptom. In hospital, the living lie intermingled with the dead.

Rush writes to a black minister called Richard Allen, a leader of the Free African Society, explaining his conviction that the fever “passes by persons of your color,” and that, as such, members of Allen’s community were “under an obligation… to attend the sick.” Allen and his colleague Absalom Jones trust his assertion, and agree: “it was our duty to do all the good we could to our suffering fellow mortals,” they later wrote.

In late September a middle-aged white widow called Margaret Hill Morris, who was tending to her sick son (“his skin was yellow as gold”) writes to her sisters that a friend “sent a black man and woman to me – who were but just done nursing in another place.” The following month, after her son has died and her household continues to battle infection, Morris writes again: “yesterday the woman I had hired took sick & left me & today the black man was also seized with the same & is gone…”. Burial records later reveal that about 240 black people will die during the 1793 epidemic – a rate of death approximately proportional to their white counterparts.

But in November, Matthew Carey, a Philadelphia bookseller publishes a pamphlet in which he claims that though the city’s black population “did not escape the disorder… the number that was finally affected, was not great.” He writes that the demand for nurses "afforded an opportunity for imposition, which was seized upon the by the vilest of blacks." Jones and Allen pen a rebuttal to his accusations of extortion: Carey has “made more money by the sale of his “scraps” than a dozen of the greatest extortioners among the black nurses.” In fact, they prove, these African Americans “worked at the peril of their lives."

Jones and Allen title their pamphlet A Narrative of the Proceedings of the Black People, During the Late Awful Calamity in Philadelphia, in the Year 1793. A document of racial injustice and the inequalities that epidemic disease can worsen and propagate, it will be the first copyrighted pamphlet written by black authors in the young nation’s history.