Antimicrobial resistance emerges as a bigger killer in Africa than malaria, HIV or TB

Antimicrobial resistance is a ‘silent pandemic’ threatening the lives of millions on the African continent, says new report.

- 17 September 2024

- 4 min read

- by Priya Joi

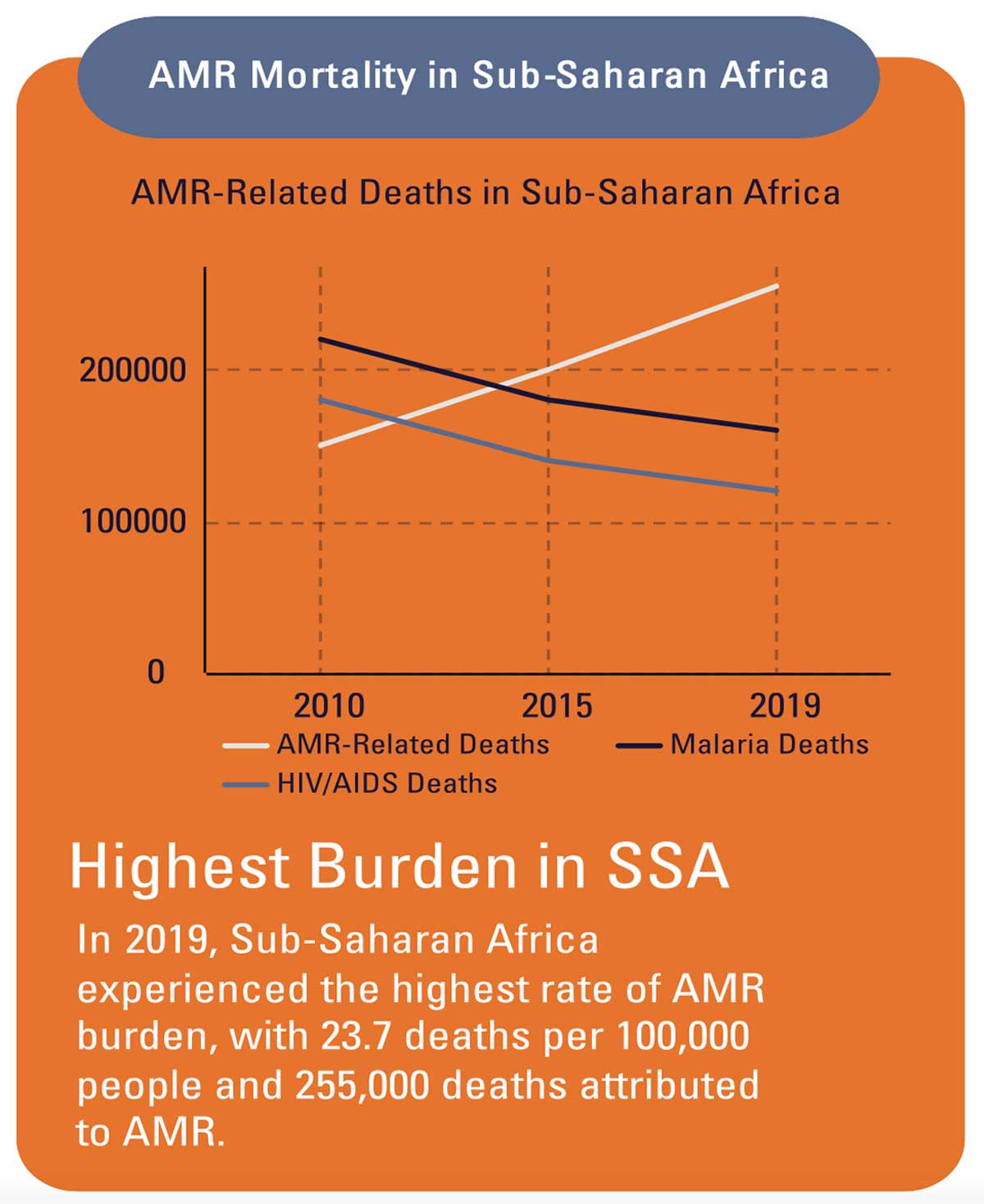

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) has emerged as a bigger killer in Africa than malaria, HIV or tuberculosis – till now the three major causes of death on the continent. In 2019, AMR was linked to around 55,000 deaths from HIV and 30,000 from malaria. According to a Lancet study, in 2019 there were an estimated 1.05 million deaths associated with bacterial AMR and 250,000 deaths directly attributable to bacterial AMR in the WHO African region.

Although AMR is a global crisis, sub-Saharan Africa carries by far the highest burden with 23.7 deaths per 100,000 people, compared to 5 per 100,000 in North America, for instance. Notably, AMR-related deaths are rising in sub-Saharan Africa as HIV/AIDS and malaria deaths are falling.

The stark realities of this crisis is detailed in a landmark report published in August 2024 by the Africa CDC (Centres for Disease Control and Prevention), a public health agency of the African Union (AU). The AU consulted with a series of experts in public health, microbiology and veterinary medicine to form an African perspective on the issue.

The report has been carefully timed – next week, the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) will hold the second-ever High-Level Meeting on AMR, in an urgent bid to galvanise action towards fighting the threat. Health experts in The Lancet are urging for ambitious 2030 targets; they are calling on world leaders to commit to reducing AMR mortality by 10%, inappropriate human antibiotic use by 20% and inappropriate animal antibiotic use by 30%.

The urgency is warranted, as the situation on the African continent is expected to worsen, says the report, “with projections indicating that by 2050, the African population will double and AMR-associated deaths could quadruple to 4.1 million per year.”

What’s more, macro trends in Africa, such as climate change, urbanisation (3.5% growth per year to 2050), agriculture-led economies (17% of total GDP for sub-Saharan Africa with a five-year growth of 13% in productivity), and the spread of zoonotic diseases (ten-year growth of 63%) will exacerbate AMR.

The report underscores the critical situation in Africa, where the burden of antimicrobial resistance is particularly severe due to factors like overuse of antibiotics in health care and agriculture, inadequate infection prevention measures and a lack of robust surveillance systems. The AU’s report reveals alarming data on resistance patterns and emphasises the disproportionate impact on vulnerable populations, including children and the elderly.

Fighting AMR requires funding, and this is currently falling far short of what is required. The financial requirements for an effective AMR response in Africa are estimated to be US$ 2–6 billion per year, yet current funding falls short by a factor of ten compared to other major disease areas.

The estimated annual budget for AMR national action plans is just US$ 100 million – which is between 1% and 5% of what is needed.

Investment would bring significant collateral benefits. For example, investing in water, sanitation, hygiene and infection prevention efforts would massively reduce the direct cases and deaths from infectious diseases, as well as potentially averting up to 20% of AMR-linked deaths in Africa each year.

A key feature of the 2024 report is its call for a unified response from African nations. It advocates for the strengthening of national action plans that align with the AU's continental strategy on AMR. This includes improving laboratory capacities, enhancing data collection and sharing, and promoting stewardship programmes to ensure the rational use of antimicrobials. The report also stresses the importance of public education campaigns to raise awareness about AMR and its implications.

Additionally, the report highlights successful case studies from African countries including Malawi and Kenya that have made strides in combatting AMR; this is crucial in acknowledging successes that the continent can build on and provides valuable lessons and models for others to follow. While there is much to be done, these examples indicate that African countries aren’t starting from zero.

The Africa CDC report is intended as a rallying cry for collective action and underscores the necessity for a robust, multi-faceted approach to preserve the effectiveness of antimicrobials for future generations. “If left unaddressed,” the report warns, “AMR will drive much of Africa into extreme poverty and cause significant annual losses in Gross Domestic Product.”