From biodefence to the DRC: How the Ebola vaccine became one of the fastest vaccines to license in history

COVID-19 vaccines are set to become the quickest vaccines in history to go from initial trials to rollout, but what lessons can we learn from its speedy predecessor: the Ebola vaccine?

- 12 January 2021

- 10 min read

- by Gavi Staff

From today, Ebola vaccines will be available to all countries for outbreak response as part of a Gavi-funded global emergency stockpile. This will mean that for the first time up to 500,000 licensed doses of the Ebola vaccine will be ready to deploy at the earliest sign of an outbreak, with Gavi-eligible low- and middle-income countries able to access doses free of charge, along with support for operational costs to respond to outbreaks. For the first time in history, we are ready the next time Ebola strikes.

This vaccine, manufactured by Merck Sharpe & Dome (or Merck as it’s known in the United States and Canada), has already helped end the recent outbreak of Ebola in the north of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), the country’s fourth in four years. Over 40,000 people were vaccinated over the course of the outbreak. This life-saving vaccine was available thanks to an unprecedented global effort to make this one of the fastest vaccines to license in history. MSD’s Ebola vaccine made it through the process in just five years, half the time it would normally take for a vaccine. But what made this vaccine development so comparatively quick and, with COVID-19 vaccines set to break all speed records, what lessons can we learn for the current vaccine effort?

A neglected disease

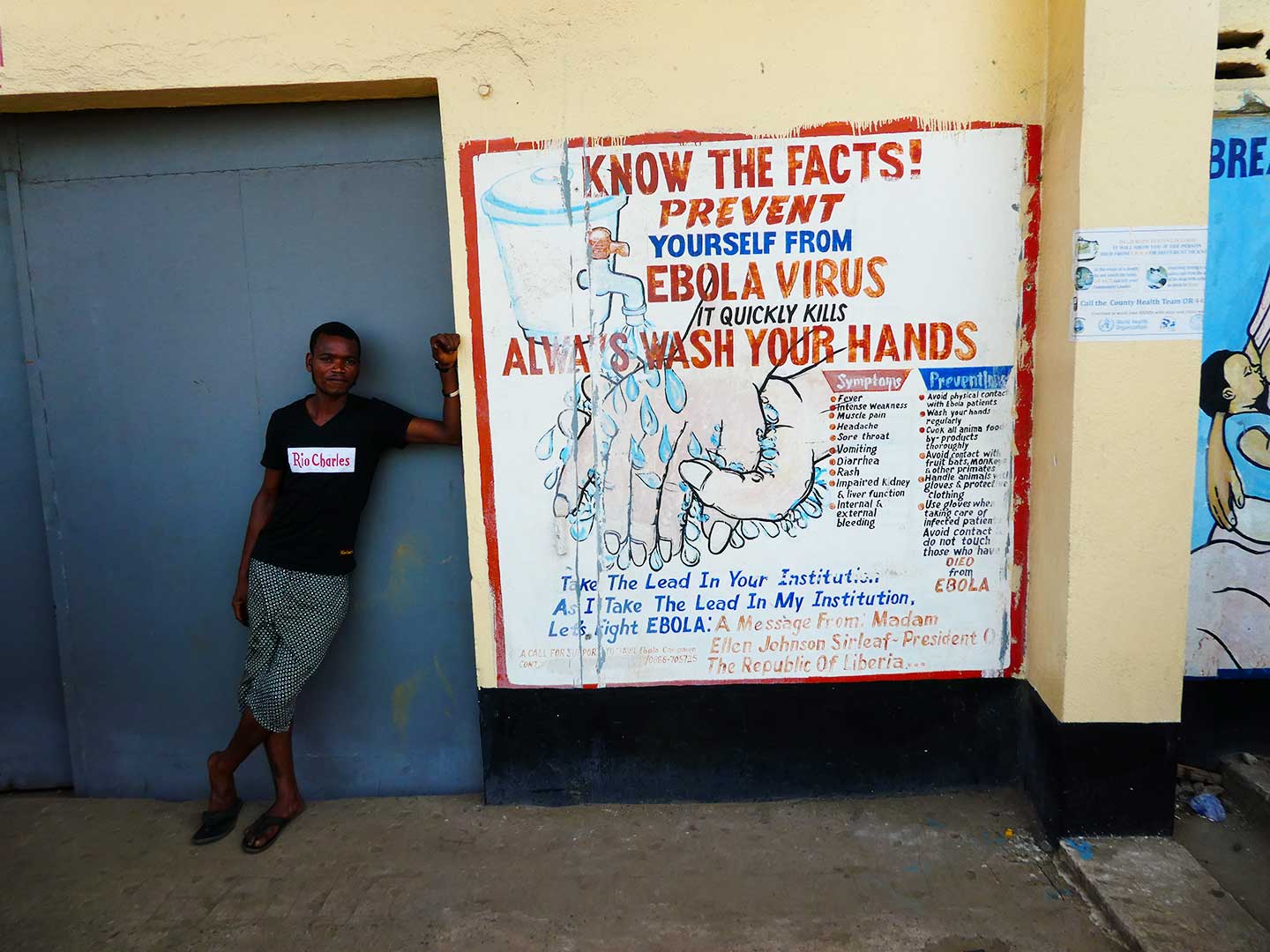

Between its first documented appearance in 1976 and the 2014-16 epidemic in West Africa, the Ebola virus infected about 2,400 people in just a handful of countries, including DRC, Uganda, Sudan and other central African states, killing nearly 1,600 of them. Despite Ebola’s horrific symptoms and mortality rate, there was no real commercial incentive to invest in a vaccine for a disease that affected so few people in parts of the world with far bigger health priorities.

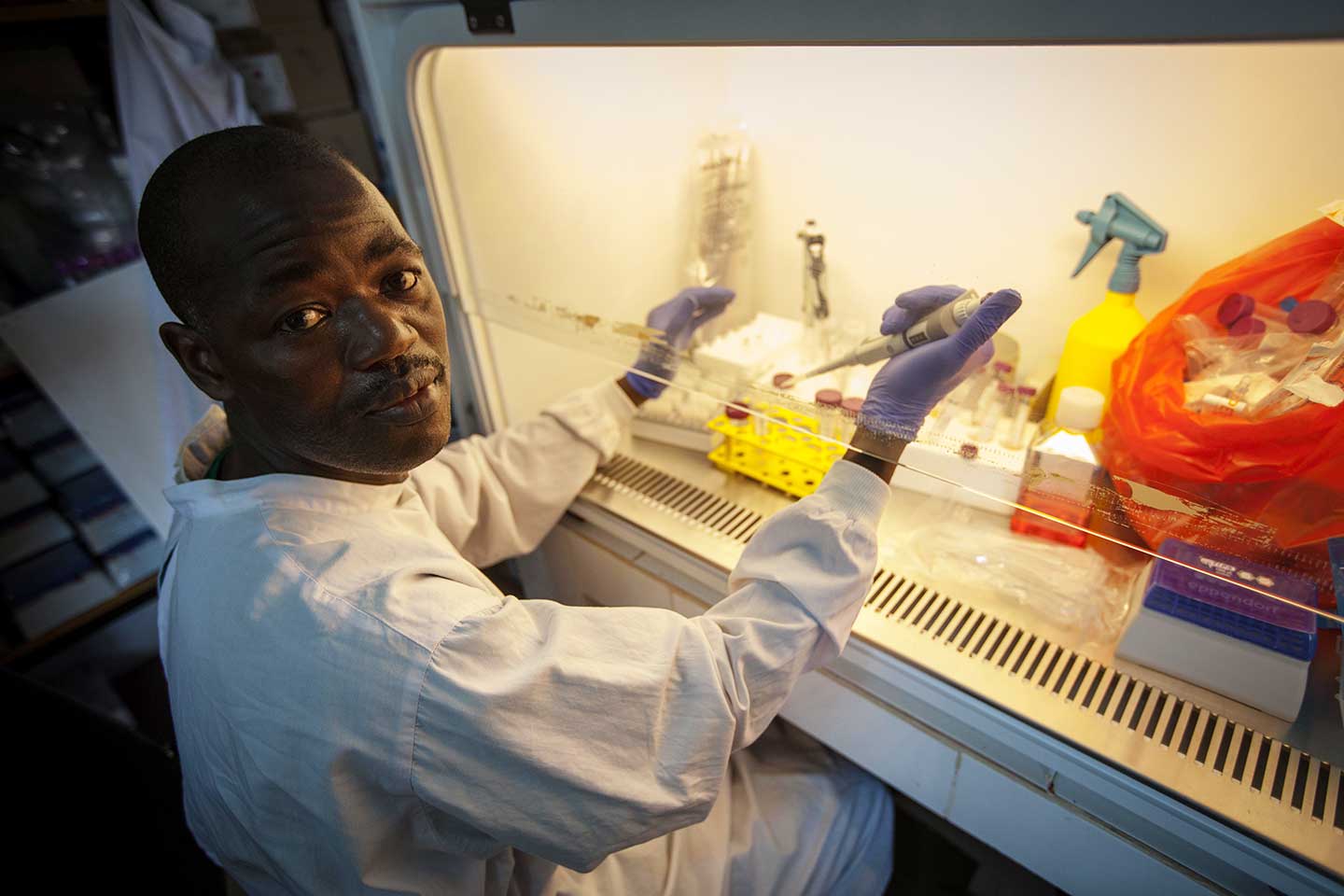

But during this time there was one sector that did see the potential dangers of Ebola: biodefence. Fuelled by fears that Ebola could be turned into a bioweapon, scientists were employed by defence agencies to begin research on vaccines and treatments. This effort was dramatically scaled-up following the terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001, with the US in particular increasing biodefence funding. Significant funds were spent developing vaccines and drugs to protect against Ebola that could be deployed if the virus was weaponised and intentionally released.

By the beginning of 2014, ten Ebola vaccines and treatments were in various stages of research, development and clinical testing. The USA was not alone in funding biodefence research related to Ebola. Canada’s Department of National Defence invested US$ 7 million in developing an Ebola vaccine at its National Microbiology Laboratory. But still no commercial market for Ebola vaccines existed.

The West Africa outbreak changes everything

But that year everything changed. In December 2013 reports began emerging of Ebola cases in a forested rural region in south-east Guinea. By July it had spread to the capitals of Liberia and Sierra Leone. By August it was posing enough of a threat to the region and the world, with cases appearing in Europe and North America, that the World Health Organization (WHO) declared it a Public Health Emergency of International Concern. This long-neglected disease was now making front pages across the globe.

That same month, Canada’s federal government donated the vaccine it had researched for biodefence purposes for use in Africa, with the Public Health Agency of Canada licensing its manufacture to NewLink Genetics and MSD.

In 2015, MSD’s vaccine was tested in Guinea, where health officials implemented the “Ebola, ça suffit” (“Ebola, that’s enough”) vaccination trial. Almost 12,000 people who had come into contact with someone who had shown symptoms were vaccinated either immediately or after 21 days. The measured efficacy was 100% (with a calculated lower confidence interval of 68.9%) using a ‘ring vaccination’ strategy – essentially ensuring every contact of a suspected case, as well as the contacts of those contacts, received the vaccine, creating a ring of immunity around every Ebola case.

The vaccine proved to be well tolerated and effective in adults. There was hope.

However, with the outbreak beginning to diminish, there remained a risk that the commercial incentive to take the vaccine through to full licensure – a long, expensive process – would still not be there, leaving this potential game-changer languishing at the trial stage.

Providing an incentive

That’s why in 2015 Gavi made a unique offer to all manufacturers that had an Ebola vaccine in phase 1 clinical trials or beyond. It offered a pre-paid commitment to buy doses of licensed vaccines as and when the vaccine becomes available. This confirmed to the manufacturers that there was a guaranteed market for an effective Ebola vaccine.

In return, Gavi set three conditions: that the manufacturer submits an application for licensure by a set date; that they submit to the WHO an application for Emergency Use Assessment and Listing, a special classification that would allow the vaccine to be used in case of a public health emergency prior to licensure; and, most importantly, that they create and maintain a stockpile of investigational doses available in case of an outbreak prior to licensure.

In January 2016, Gavi announced that MSD had agreed to these terms. An Advance Purchase Commitment – the first of its kind – was signed. This agreement meant that investigational doses of the MSD vaccine would be available in case of an outbreak, even before the vaccine had been fully licensed by regulators.

Have you read?

The vaccine gets its first rollout

The stockpile saw its first use in the DRC in 2018, where an outbreak in the northern city of Mbandaka infected 54 people, killing 33. Over 3,000 people were given the vaccine, helping to bring a swift end to the outbreak. Importantly, nobody who received the vaccine contracted Ebola.

In 2019, a far more serious outbreak in the war-torn eastern region of the country would prove a much sterner test. As cases rose rapidly in North Kivu and Ituri provinces, threatening to spread into bordering countries Rwanda, Uganda, Burundi and South Sudan, a repeat of the West Africa outbreak just a few years earlier was a very real possibility.

The stockpile was immediately put to use, with Vaccine Alliance partners such as the WHO supporting the government’s efforts to implement a ring vaccination strategy in one of the world’s most difficult regions.

Not only was the context challenging, but the vaccine itself brought with it complexities that needed to be solved to ensure it could reach the people that needed it. Unlike regular drugs, all vaccines need to be transported and stored at certain temperatures to remain effective. For the vast majority this means keeping them in fridges at between 2 and 8 degrees Celsius. The Ebola vaccine, however, needs to be kept at -70 to -80 degrees Celsius – colder than most household freezers. In an equatorial region with intermittent electricity, poor roads and few health clinics, this could have been an insurmountable challenge.

However, the heroic efforts of Congolese vaccinators, logisticians and health workers meant over 300,000 people in DRC and neighbouring countries consented to and received the vaccine, with doses taken from the investigational stockpile.

Technology also played a role. The Arktek vaccine storage device, developed by Intellectual Ventures Laboratory, makes use of the same technology used to protect spacecraft from extreme temperatures to store vaccines as low as -80 degrees Celsius, without electricity. With funding from Gavi, these were deployed across the region to ensure vaccines could get to where they needed to be.

On 25 June 2020 the second largest Ebola outbreak in history was finally declared over, after it had claimed the lives of over 2,000 people. The vaccine played a key role, as WHO Director General Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said after the declaration: “the Ebola response was a victory for science. The rapid rollout of highly effective vaccines saved lives and slowed the spread of Ebola.”

However, just as this serious outbreak was brought under control, in June 2020 a new epidemic broke out in Equateur province, the same region as the 2018 outbreak. Again, the vaccine was put to work. After the vaccination of more than 40,000 people, today the country’s fourth outbreak in as many years was officially declared over. With 130 people infected, 55 people lost their lives to the disease. Without the vaccine this toll could arguably have been far higher.

Ebola becomes a preventable disease

While the vaccine was busy protecting hundreds of thousands of people in the DRC, in November 2019 MSD’s vaccine was granted EU-wide conditional marketing authorisation by the European Commission, following a recommendation by the European Medicines Agency (EMA).

Forty-eight hours later the WHO prequalified the vaccine – meaning it could be procured by UN agencies – sending a signal to regulators around the world that this was a safe and effective vaccine. This was quickly followed in December by approval from the US Food & Drug Administration (FDA). Five years after those first wide-scale trials in West Africa, we had a fully licensed, safe and effective vaccine. Ebola was now a preventable disease.

Lessons for COVID-19

So, as we prepare for the rollout of COVID-19 vaccines what lessons can we learn from the Ebola vaccine?

Firstly, nothing sharpens minds like a deadly virus that appears to be running out of control. The MSD vaccine was taken off the shelf and dusted down in the midst of the worst Ebola outbreak in history, with large-scale trials done carefully, yet quickly, in countries where the urgent need for it couldn’t be clearer. Safety remained paramount, with the right protocols followed and safety signals monitored closely, just as we are seeing with COVID-19 vaccines currently going through trials. The need for speed does not mean any compromise needs to be made on safety.

It shows how technology can help us overcome seemingly insurmountable obstacles. Some COVID-19 vaccines that have received emergency use authorisation require an ultra-cold chain similar to that of the Ebola vaccine – -80 degrees Celsius. While an ultra-cold chain vaccine presents challenges, we know from our experience with the Ebola vaccine in DRC that it can be done.

Despite all the current talk of ‘vaccine nationalism’, the Ebola vaccine also gives weight to the idea that epidemics that threaten us all can also foster international collaboration. This was a Canadian vaccine, donated to a US company and manufactured in a German facility. Donors from across the world contributed, and continue to contribute, to its development and rollout.

With COVID-19 we are seeing former competitors, such as GSK and Sanofi, come together in the search for a vaccine. More than 180 countries are engaging with Gavi’s COVAX Facility, which is seeking to guarantee rapid, global access to these vaccines as they reach licensure and prequalification. Again, nationalism is increasingly being pushed aside in favour of working together to defeat a common enemy.

Finally, the Ebola vaccine’s rapid move from development to licensure shows how a well-timed intervention, working with industry and the governments involved, can help create the incentives needed to ensure new vaccines can be rolled-out globally and at speed.

Gavi’s Advance Purchase Commitment sent the signal to manufacturers that there would be a market for Ebola vaccines even after the West Africa pandemic ended. With COVID-19 the risk is different – there certainly isn’t the need to guarantee a market for arguably the most anticipated vaccines in history. The need right now is to create the incentive and secure the finance needed to ensure enough doses are manufactured for the world, rather than just for the richest few countries.

This is why Gavi is using its years of experience with the Ebola Advance Purchase Commitment, as well as the pneumococcal vaccine Advance Market Commitment, to help guide COVAX – our best hope at ensuring countries and economies worldwide, rich or poor, get rapid access to COVID-19 vaccines. The stakes couldn’t be higher but, just as with Ebola, the reward could be historic: making COVID-19 a preventable disease.