Book Review: How Sickness Has Transformed Civilization

“The Great Shadow,” by Susan Wise Bauer, is a sweeping survey of humanity’s relationship to illness over the centuries.

- 18 February 2026

- 7 min read

- by Undark

On a cold spring day in 542 AD, a galley ship dropped anchor at the Golden Horn in Constantinople, bearing a load of grain from Egypt. Workers swarmed the ship, unloading much-needed supplies that would feed the hungry city. But the delivery came with a cost. Soon, the Byzantines started falling ill. With fevers. With swelling in their armpits and groins, or black lentil-sized pustules. They raved, they fell into comas, they perished. The city’s towers became makeshift grave pits. Along with sickness, fear stalked the city: “Walking home through the streets, you might hear a disembodied voice whisper death into your ear and know that you were doomed.”

Sickness is an experience that’s touched every human being and community since the beginning of time. In her latest book, “The Great Shadow: A History of How Sickness Shapes What We Do, Think, Believe, and Buy,’’ historian and author Susan Wise Bauer tackles an ambitious project: in some 300 pages, she weaves the story of humanity’s relationship to illness over the past four millennia, from ancient Sumerians calling on priests to prescribe incantations against cold-causing demons to those Byzantines facing the horrors of the plague to Victorians terrified of “sewer gas” drifting out of their toilets.

By weaving an intellectual, medical, and social history of our relationship with illness, Bauer aims to show just how much of modern society has been shaped by our forbears’ fears and beliefs. Her central argument is that “it is the constant presence of sickness, not injury, that has shaped the way we think about ourselves and our world.” In the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic and in the midst of increasing distrust of medical science, writes Bauer, it’s more important than ever that we understand how we got here, and what that means for our future.

Unlike most nonfiction authors, who open with an introduction or preface outlining their thesis and main points, Bauer throws us almost immediately into the Neolithic Revolution, when humans settled down to farm.

She explains that when humanity started living in close proximity to one another and to livestock, diseases such as malaria, diphtheria, and smallpox started their slow and evil evolution. Her narrative continues at breakneck speed, covering ancients’ exhortations to gods, early physicians’ attempts at using actual treatments to combat illness, and the turning point catalyzed by Hippocrates, whose theory of disease as caused by imbalance of humors took root in ancient Greece and lasted for nearly 20 centuries. Under this schema: “People didn’t ‘get sick.’ They slipped slowly into imbalance as their lives went askew. Righting that imbalance could lead to a cure.”

“It is the constant presence of sickness, not injury, that has shaped the way we think about ourselves and our world.”

Then the Dark Ages dawned, Hippocrates’ teachings rendered powerless as the plague ripped through Eurasia and destroyed millions of lives. People tried sleeping with apples in hopes that the sweet scent would keep their humors in balance; they tried leaving cities, consulting astronomers. Bauer evocatively asks us to imagine ourselves in that time and place: She writes it’s “easy for us to sweep our eyes over those figures: but now summon to your mind the people you know, and then imagine that half of them are suddenly gone forever.”

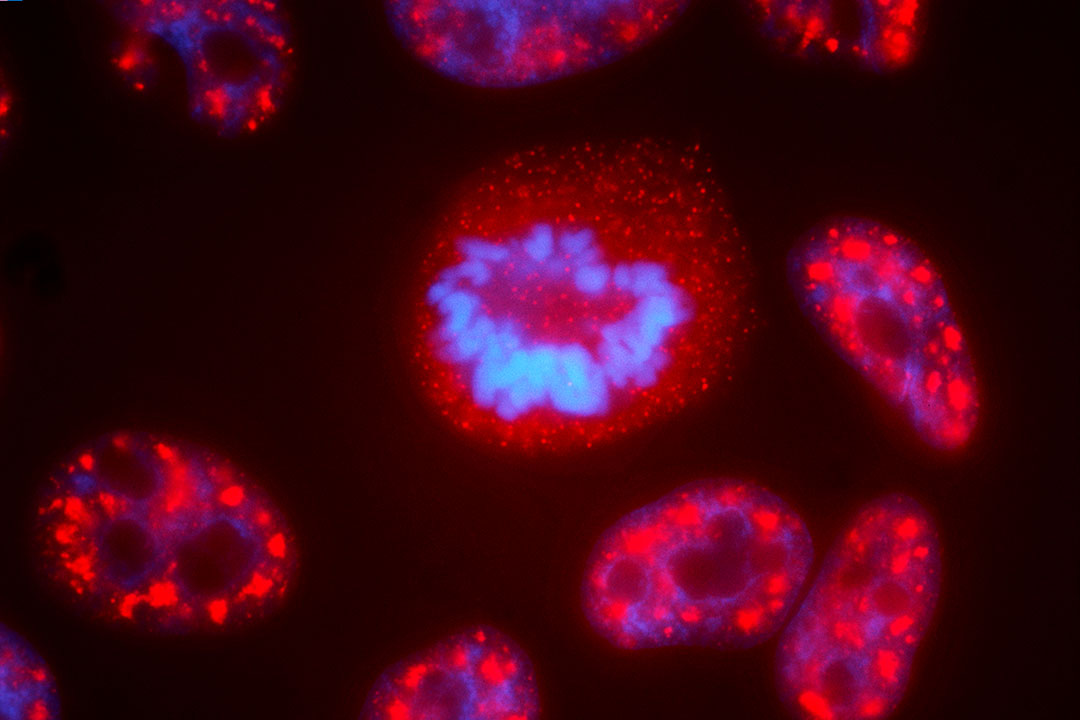

After the dawn of modernity, the twists in Bauer’s story come fast. Drugs, notably laudanum, changed the experience of pain. An Italian physician theorized that sickness stems from microscopic “seeds,” the beginning of germ theory. Victorians balked at the idea that disease could be caused by contagion, since the new bourgeois classes preferred to believe that only the “intemperate and dissolute” could fall victim to maladies like cholera. German doctor Robert Koch proved germ theory once and for all by discovering that a particular bacteria caused tuberculosis. Bauer covers the rise of vaccines, the transformative invention of antibiotics, the mid-20th century conviction that we’d cheated death with these new technologies, the somber realization, with the advent of Ebola, AIDS, MRSA, and now Covid, that our optimism was misplaced.

Bauer’s narrative is a page-turner, which makes sense. This is, in essence, a horror story. At its core, it’s about humanity desperately trying to understand and defeat an ever-mutating foe, often with little chance of survival. Bauer also achieves this page-turner effect through short chapters, beautiful writing, and, most crucially, characters. She sometimes addresses an imaginary “you,” forcing the reader to, for example, imagine themselves as an early-modern butcher suffering from chronic pain. More often, she uses techniques drawn from the realm of fiction writing to immerse the reader in the bodily experiences of real people from history.

Vividly and chillingly, we experience what it was like to witness early anatomical dissections; to arrive in the Virginia colony as a British boy, watching companions perish of the “bloody flux,” to give birth in the 1700s and, while still bleeding, watch your newborn boy slowly but surely fail to thrive. Bauer brings us into these scenes with details, describing “the sweet, dark smell of the rags” and “the warm, yeasty scent of his head.”

Throughout this narrative, Bauer advances her argument that many facets of our society today are shaped by these ancestors and their beliefs. Our obsession with disposable goods, from menstrual products to cups, stems from the cleanliness obsession that followed the discovery of germ theory in the early 20th century, as does our enthusiasm for soaps, cleaning supplies, and other products that smell good (“there is, after all, no other excuse for plug-in air fresheners,” as Bauer wryly notes).

Anyone who’s ever cautioned their child to put on a coat lest they catch a cold is unwittingly parroting Hippocratic notions of imbalance causing illness. And anyone who’s ever refused a vaccine is following in a long tradition of viewing these life-saving, disease-defying innovations as a challenge to individual freedom: Naysayers were calling them “latter-day tyranny” as long ago as 1853.

In the midst of increasing distrust of medical science, writes Bauer, it’s more important than ever that we understand how we got here, and what that means for our future.

Sadly, anyone who’s ever villainized the other as filthy a bearer of plague is also following in a long tradition, from medieval Christians who blamed Jews for the plague to an elderly relative forbidding Bauer from swimming in a pool with Black kids. And, most perniciously, since ancient times, sickness has been connected with morality. This tendency to blame the sick for their misfortune stretches from ancient Chinese consulting oracles about ancestors’ displeasure to the West Virginia state government, in 2006, requiring Medicaid recipients to sign a personal responsibility agreement before receiving their full benefits.

At times, one senses that Bauer is straining to fit various threads into her argument. For example, she argues that Hippocratic theory drove decisions about where to settle the North American continent, with well-to-do British, whose bodies naturally belonged in temperate climates, sent to New England and criminals, whose temperament belonged in heat and humidity, sent to the South. She claims that this colonial enterprise was shaped by “above all, our wish to stay healthy” and argues that the “lasting effects of Hippocratic theory” are evident in the differences between the two regions today, pointing out that Southern states are still much poorer than their Northern counterparts.

Hippocratic theory certainly played a role in British perceptions about different regions in the American colonies, as Bauer shows through primary documents. But to suit her narrative, she downplays large swaths of history and far more important factors that shaped the North and South over the centuries.

This is, in essence, a horror story. At its core, it’s about humanity desperately trying to understand and defeat an ever-mutating foe, often with little chance of survival.

Still, although some of Bauer’s claims are a stretch, her book overall makes an important point. She signed her contract for “The Great Shadow” in December 2019, but the subsequent years during which she was writing her manuscript proved her central point in real time. Especially when faced with dire circumstances like the pandemic, we replay, “unthinking, almost every beat of the last few centuries of our relationship with infectious disease,” from blaming the other to slathering ourselves in scented sanitizer to chasing hail Mary quack cures.

As Bauer writes, during the first plague in 542, “the frightened citizens of Constantinople bought charms and amulets; the frightened people of 2020 put their faith in cocaine, vodka, Alex Jones’s propriety toothpaste, colloidal silver, bleach, and hydroxychloroquine.”

Can we break out of our centuries-old beliefs and habits around illness? Bauer isn’t sure, but she argues that understanding this history, and the age and persistence of our gravest and silliest misconceptions about health and sickness, is a step in the right direction.