Book Review: The Urgent Quest to Prevent the Next Pandemic

In “Planning Miracles,” Jon Cohen chronicles the efforts of scientists and others to eradicate the threat of pandemics.

- 24 November 2025

- 7 min read

- by Undark

In 1938, President Franklin D. Roosevelt created the organization now called March of Dimes, with the goal of wiping out polio, the viral disease that caused his paraplegia. Just 17 years later, clear evidence arrived that Jonas Salk’s polio vaccine was effective — the first step in the near-total eradication of polio around the world. In the organization’s 1955 annual report, its top executive called the vaccine a “planned miracle.”

In “Planning Miracles: How to Prevent Future Pandemics,” science journalist Jon Cohen introduces readers to biologists, veterinarians, epidemiologists, and others who are trying for another miracle: to blunt pandemics, or even prevent them altogether.

Cohen, a longtime correspondent for Science magazine, traveled the globe to document the vast amount of work being done to identify emerging threats, along with the vaccines and other containment practices to stop their spread. The sheer volume of effort is a reason for hope. But polio had one highly visible attribute — a world leader partially paralyzed by the disease — that our viral diseases today do not have.

In Cohen’s view, the lack of leadership that keeps focused on pandemic prevention even after a crisis has passed tempers the hope offered by science. “We repeatedly move from ignoring the threat that viruses and other pathogens present to panicking when they surface and cause widespread harm,” he writes. “And then, when the crisis passes, we neglect them again.”

Over much of history, of course, no one knew anything could be done to prevent pandemics. Plagues have been documented as far back as 430 B.C., Cohen writes, when a deadly disease started in Ethiopia, then spread to Egypt and on to Greece, where it wiped out a quarter of the Athenian population.

Although some quibble about the definition, the word pandemic generally applies to an epidemic — a disease that affects an entire population — that crosses international borders. Pandemics can be caused by bacteria and viruses, among other things. Cohen focuses on viruses, the root cause of modern-day plagues like Covid-19, mpox, influenza, Ebola, West Nile, dengue, yellow fever, and HIV.

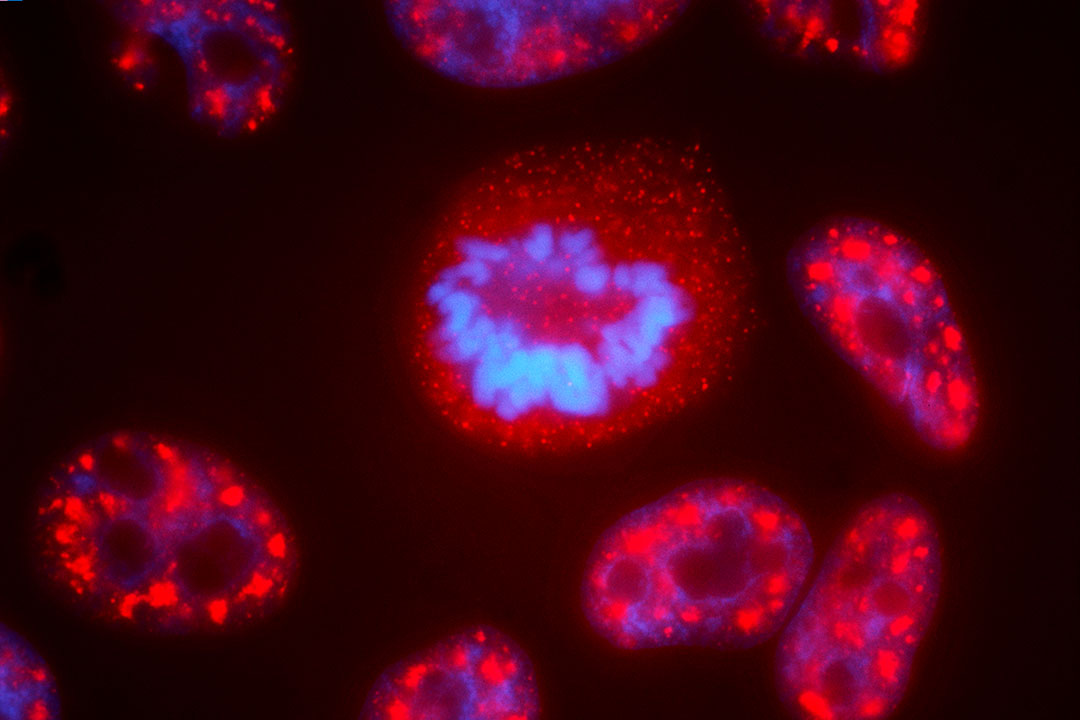

Viruses on Earth may outnumber the stars in the universe, Cohen writes, but only a tiny fraction are cause for alarm. The bad ones are those that have the genetic makeup needed to copy themselves, the attributes that cause illness, and — crucially — the ability to get inside human cells and move from one person to another.

“We repeatedly move from ignoring the threat that viruses and other pathogens present to panicking when they surface and cause widespread harm.”

Those dangerous viruses get access to human cells by leaping from animals to humans in a process called zoonosis. The culprits include birds, bats, pigs, civet cats, raccoon dogs, cows, and many other animals that transmit viruses to humans by spewing saliva, depositing feces, and various other methods.

After documenting the potential for lifesaving vaccines — and the pitfalls of developing, producing, purchasing, stockpiling and equitably distributing them — Cohen turns his attention to avoiding the need for them. “Surveillance attempts to know where the threats lurk so we can reduce the risks of outbreaks or, if they happen, quickly recognize the culprit and cut it off before it leads to a pandemic,” Cohen writes.

Among many other locations, Cohen’s reporting took him to a hog show in Iowa, birding expeditions in Sweden, and a bat-sampling initiative in Brazil to see how experts are trying to get ahead of future disease outbreaks. At every opportunity, Cohen gives vivid details — orange-colored whole roasted pigs, crabs the size of two fists, and mountains of dried fish at an outdoor market in Phnom Penh, for example — that let readers tag along on his adventures.

On his visit to that market in Cambodia, he was clearly impressed with an epidemiologist’s innovation — a small hand-held device that, held close to chickens being slaughtered in the market, collects air samples to search for viral RNA. The AeroCollect, as it is called, and other devices are being developed to make virus surveillance “simpler, faster, cheaper and safer.”

“Several other scientists around the world are tapping advances in nanotechnology, sequencing devices, artificial intelligence, and robotics to improve virus hunting,” he writes, “and provide a deeper, more timely understanding of potential threats.”

Cohen inspires readers to be optimistic that scientists will win the war against viruses. But he is a journalist, not a hypester, and at every turn we are reminded that pandemic prevention presents challenges beyond science.

In one example, he shows how scientists can become embroiled in political controversies that limit their ability to continue their work. He homes in on the work of Peter Daszak, a conservation biologist who Cohen calls “one of the world’s most prominent virus hunters.” Daszak was one of a small group of scientists who convened in 2016 to plan a huge initiative — the Global Virome Project, or GVP — that would identify 75 percent of the viruses most likely to emerge in humans within 10 years.

It’s the kind of comprehensive effort that might make good sense to lay readers, but it was derailed when the very idea of discovering viruses became controversial — collateral damage from what Cohen calls the “Great Origin Debate” over whether Covid-19 started from a laboratory leak in China.

Daszak’s organization, EcoHealth Alliance, had a federal grant that awarded a subcontract to the suspected laboratory, and Daszak was accused of withholding critical information about the possibility of a lab leak. President Donald Trump’s administration started maligning Daszak’s organization in 2020 and, in early 2025, banned both him as an individual and EcoHealth Alliance from receiving federal funding for five years. EcoHealth Alliance disbanded earlier this year.

Cohen says the lab leak hypothesis — which has been the subject of intense debate — warranted investigation. But, in his view, the virulent attack on the scientists who were investigated introduced a new threat that further imperils the world: “By relentlessly, viciously denigrating leading scientists who have devoted their careers to studying the forces that drive outbreaks and trying to prevent them from growing into pandemics, these critics increase the risk that experienced people will be forced to curtail or abandon their pandemic prevention research.”

Other pandemic problem-solvers are simply victims of the public’s panic/neglect cycle. One example: As Covid-19 rolled across the world, the U.S. government realized that face masks needed work. Some masks are much better than others at cutting down on the transmission of aerosols. And masks are only effective if they are used, which makes comfort and appearance important.

Many years before the pandemic, Richard Gordon and Min Xiao, a husband-and-wife team, had started a company, Air99, to develop an origami-inspired mask that could reduce the danger of breathing polluted air. When the federal government launched the Mask Innovation Challenge, offering $500,000 in prize money to the mask that offered the best fit, function, and look, Air 99 jumped in.

Have you read?

Its product — Airgami, available in four sizes and various colorful designs aimed to appeal to everyone from Dead Heads to military enthusiasts— beat out 1,447 competitors when the winner was announced in November 2022. But the public’s enthusiasm for face masks was already waning and in November 2023, Air99 went out of business.

“Planning Miracles” is one of many book-length wake-up calls, dating back at least to the early 1980s, about the threat of viral pandemics. Cohen gives a hat-tip to many of them, particularly praising “The Coming Plague: Newly Emerging Diseases in a World Out of Balance,” published in 1994, in which Laurie Garrett warned that HIV should be seen not as a public health aberration but a possible “sign of things to come.” And Cohen cites a different perspective — Donald G. McNeil Jr.’s recent “The Wisdom of Plagues: Lessons from 25 Years of Covering Pandemics” — because it details the social factors, including political opportunism and ill-informed media, that damaged the world’s response to Covid-19.

Cohen’s sprawling assessment of the prevention landscape makes a compelling case that the most essential weapon against future pandemics is the will to prevent them.

Cohen’s own contribution to the growing shelf of pandemic-related titles offers readers a glimmer of hope: “We have the brains and the technologies to better protect ourselves from zoonotic jumps, reducing their frequency, more quickly thwarting outbreaks that do occur, and responding more effectively to ones that become epidemics and pandemics,” he writes.

His sprawling assessment of the prevention landscape makes a compelling case that the most essential weapon against future pandemics is the will to prevent them. Among other things, that means a sustained effort to develop and stockpile vaccines for the most likely threats rather than using Operation Warp Speed — the vaccine-development push that Cohen calls a “daring mission that could well have failed” and that succeeded in part by pure luck — as a blueprint for future pandemics.

He reels off other possibilities that give him hope — among them, an internationally coordinated surveillance system, vaccines that work against entire families of viruses, antiviral drugs that work against multiple targets, and better masks — but argues that we are “playing footsie with pandemic prevention.”

“We know the way,” he writes. “We do not have the will.”