Book Review: The Strangers Within Us

“Hidden Guests” explores how the emerging field of microchimerism is upending medicine, genetics, and our sense of self.

- 1 December 2025

- 6 min read

- by Undark

In March 1953, a healthy 28-year-old woman donated blood at a clinic in northern England. As technicians tried to determine her blood type, they could hardly believe what they saw. The woman, identified as Mrs. McK, had both type O and type A red blood cells. The results contradicted a central paradigm of 20th century medicine, which stated that people can only have one blood type — A, B, AB, or O.

When Robert Race, a blood-type specialist in London, received the findings, he revealed that the case wasn’t unprecedented. About a decade earlier, American biologist Ray Owen stumbled on a similar phenomenon not in humans, but in cows, in which — due to the shared placental blood circulation — twin calves had two different types of blood cells.

When asked, Mrs. McK divulged that she had a twin brother who died young. Almost 30 years later, she was still carrying her twin’s cells inside her body. The revelation was so discombobulating that Race described Mrs. McK as a “chimera,” referring to a monstrous creature from Greek mythology with a head and forequarters of a lion, a goat’s head on its back, and a serpent for a tail.

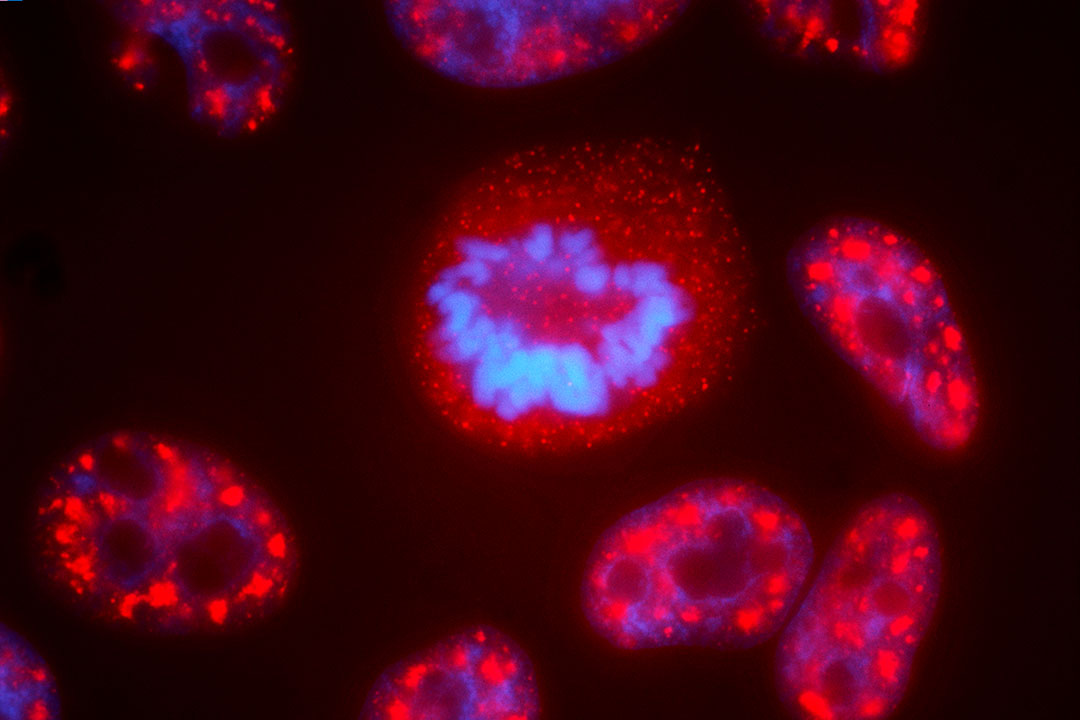

This is only one of many mind-boggling and fascinating examples of cellular trickery described by French science journalist Lise Barnéoud in “Hidden Guests: Migrating Cells and How the New Science of Microchimerism Is Redefining Human Identity.” A biological phenomenon, microchimerism refers to the presence of a small number of cells from one individual within another genetically distinct individual. It most commonly occurs during pregnancy when fetal cells escape into the mother’s bloodstream or maternal cells sneak into the placenta, eventually becoming part of the embryo or fetus. Likewise, twins may exchange cells before birth, too.

Have you read?

The cases aren’t that rare. “Approximately 8 percent of fraternal twins and 21 percent of fraternal triplets carry blood cells from their companions in utero,” Barnéoud writes, citing a 2020 review. Similarly, fetal cells that wander outside the placenta can persist in the mother’s body for years, genomic scientist Diana Bianchi discovered decades after Mrs. McK’s case, in 1993. Bianchi and her team found male cells in the blood of six women who had given births to sons from one to 27 years earlier. Male cells are easier to spot in women because they have X and Y chromosomes in their cell nucleus while female cells have two X chromosomes, and the Y chromosome stands out. But males can carry foreign cells too.

These wandering cells can settle anywhere in the body, making up “a tiny fraction of a kidney, for example, or the entire organ,” Barnéoud reveals. Some have been known to make a home in lungs and others in livers. Moreover, “microchimeric cells can cross the blood-brain barrier and take up permanent residence in our command center,” Barnéoud writes. A 2012 study of 54 deceased women referenced in the book found that 63 percent had male cells in their brains. And one far-fetched hypothesis even posits that women may also acquire foreign cells through semen. So, “if you don’t want to wind up with a head full of cells from multiple men, you’d better use protection!” writes Barnéoud.

Microchimerism refers to the presence of a small number of cells from one individual within another genetically distinct individual. It most commonly occurs during pregnancy.

“Mothers likely carry their children’s cells within them for the rest of their lives,” according to Barnéoud. Children may be carrying their parents. If your mother’s cells sneaked in, clinging to you while you were in utero, you may still harbor them. Bianchi found that maternal cells migrated into their offspring’s thymus, thyroid, liver, skin, and spleen. “So you think your mother is always looking over your shoulder?” Barnéoud quotes Judith Hall, a pediatrician and geneticist who wrote an editorial commenting on Bianchi’s findings, as writing. “She may be in your shoulder.”

Moreover, researchers now hypothesize that even your grandmother’s cells may be lurking in your body, passed on from your mother. It seems that a lot of us may be chimeras, not only Mrs. McK.

However, Barnéoud argues that by using the term “chimeric,” scientists did a great disservice to the cells, instantly casting them as villains. Understandably, they were shocked because Mrs. McK defied the laws of immunology at the time, which stated that a healthy immune system can’t tolerate foreign cells. Eventually, chimeric cells lived up to their reputation: In the mid-1990s, scientists implicated them in autoimmune diseases, which disproportionately affect women.

Sometimes, it seems, the immune system may decide to go after them, causing increased inflammation. (Except in this case the term “autoimmune” doesn’t apply because the cells indeed are foreign and the body isn’t attacking itself.) And so “these cells became migrants, intruders, vagrants crossing the placental border and colonizing, invading, or squatting on maternal territory,” Barnéoud writes. In medicine, it seems, the concept of “us” and “them” is just as dominant as in politics and wars.

It took time to realize that the “invading” cells can come in peace — and even bring benefits. Early in this millennia, scientists learned that microchimeric cells can repair wounds by forming skin and blood vessels. They also can heal heart damage; when injected into mice after a heart attack, they find a way to the damaged heart parts and fix them. And in post-mortem findings of a child who had diabetes, researchers discovered maternal cells were producing insulin in the pancreas, decreeing that the cells were likely helping to “restore function and regenerate diseased tissue.”

And just like that, the chimeric cells “have gone from being suspicious vagrants to productive immigrants, naturalized — in the political sense of the term — to their new home,” Barnéoud quotes from historian of science Aryn Martin.

Told in beautiful, sometimes bordering on poetic, language with occasional snark and humor thrown in, the book upends some of the very foundations of medicine, immunology, and genetics. And, having been rooted in cutting-edge research, it rocks our philosophical concept of self. A discovery that the microbial cells in our body may outnumber our own, made us realize we’re only partially human. Now comes the second blow to our ego — we aren’t fully one-human either. “Twenty years after the microbial upheaval, another is underway: even the human half of us does not solely consist of our ‘I,’” Barnéoud’s observes.

“The idea of an entirely independent individual self-constructed from a single fertilized egg is a myth.”

Clever chapter names — “The Other in Me,” “The Other Mes” and “I’ve Got You Under My Skin” — make you question your biological composition. You can’t help but wonder where all these “others of you” came from and how they interact with one another — and yourself. Instead of a single, uniform genome defining your biological identity, you begin to see yourself as something greater than just you.

“The idea of an entirely independent individual self-constructed from a single fertilized egg is a myth,” Barnéoud concludes. That myth may bode well with the ideals of modern Western societies, where we prioritize the individual’s rights over the needs of a collective, but in this new, emerging biological reality, no human is a true individuum. We all are living communities of cells — some ours, some ancestral, some microbial — all of which are in perpetual flux that sometimes results in health and sometimes disease.

Instead of being battlegrounds of “us” and “them,” our bodies operate on never-ending negotiations, tolerating and benefiting from genetic strangers within. “We are each of us a collective in constant co-construction,” Barnéoud resolves, “and our equilibrium depends on the interactions of our constituents.”