Building the world we want: What does Universal Health Coverage mean?

For this year’s Universal Health Coverage (UHC) day, Gavi’s Director of Public Policy Engagement sets out what UHC means and the steps we can all take to help achieve it.

- 12 December 2022

- 6 min read

- by Anamaria Bejar

Building the world that we want is the theme for this year's Universal Health Coverage (UHC) Day. The world Gavi works for is one in which every human being, no matter who they are or where they live, can receive lifesaving health services such as immunisation. In the world we want to build, zero-dose children – those who have not received even a single shot of any vaccine and often face multiple deprivations – have access to high quality services and live healthy lives.

Universal Health Coverage has the potential to make this world a reality. Investing in the right to health means lifting people out of poverty, promoting the well-being of the most left-behind and protecting families and communities in the hardest to reach areas.1

Investing in the right to health means lifting people out of poverty, promoting the well-being of the most left-behind and protecting families and communities in the hardest to reach areas.

UHC is fundamentally a political choice, one that requires determination and prioritisation. We can have all the technical fixes and shiny solutions in hand, but without the trust of communities and decisive political commitment we will struggle to make any progress.

Civic space, democracy and inclusive governance are inextricably linked with the UHC agenda. Who is included or excluded in health decision-making at every level is critical in addressing health inequities. To achieve UHC, being held to account by those who are left behind and those who face discrimination and exclusion is fundamental. Civil society and communities must therefore be included in any UHC plans from the local to the global level.

I know UHC can sometimes sound like a vague concept, but it is simple really and can be transformational. According to the World Health Organization, UHC means that "all individuals and communities receive the health services they need without suffering financial hardship. It includes the full spectrum of essential, quality health services, from health promotion to prevention, treatment, rehabilitation, and palliative care across the life course."2

Governments have committed to achieving Universal Health Coverage since the promise of Health for All in 1978, recommitted as part of the Sustainable Development Goals in 2016 and then recommitted again by endorsing a political declaration at the United Nations General Assembly High-Level Meeting on Universal Health Coverage in 2019.

Have you read?

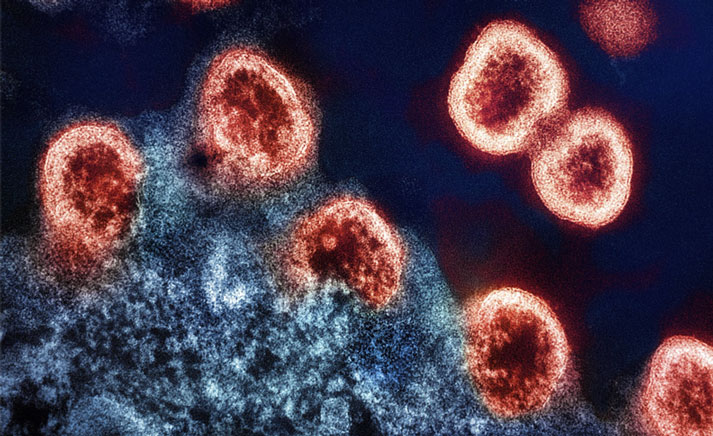

Since then, challenges to realising UHC have only become more prominent. The COVID-19 pandemic set progress back and saw political priorities shifting to face multiple interdependent challenges, from economic headwinds to climate change and widespread conflict around the world.

However, investments in UHC have the potential to greatly impact the lives of some of the poorest communities and ensure that countries are better able to prevent and prepare for future shocks such as disease outbreaks or pandemics. Investing in primary health care is crucial not only for UHC, but also for pandemic prevention, preparedness and response and global health security.

Immunisation is one of the most efficient and cost-effective services delivered at primary health care level, with the greatest reach and demonstrable health outcomes. A study covering the 73 Gavi-supported countries shows that, for every US$ 1 spent on immunisation in the 2021–2030 period, US$ 21 will be saved in health care costs, lost wages and lost productivity due to illness and death.3

If there is one critical investment governments should prioritise, it is remunerating community health workers - the heart of primary health care.

Routine immunisation programmes develop the capacity of health workers in outreach, health management information systems, cold chain capabilities and disease surveillance that are critical for many other health programmes. Routine immunisation can therefore serve as a useful platform to jointly deliver broader PHC services closer to communities, as well as to promote equity.

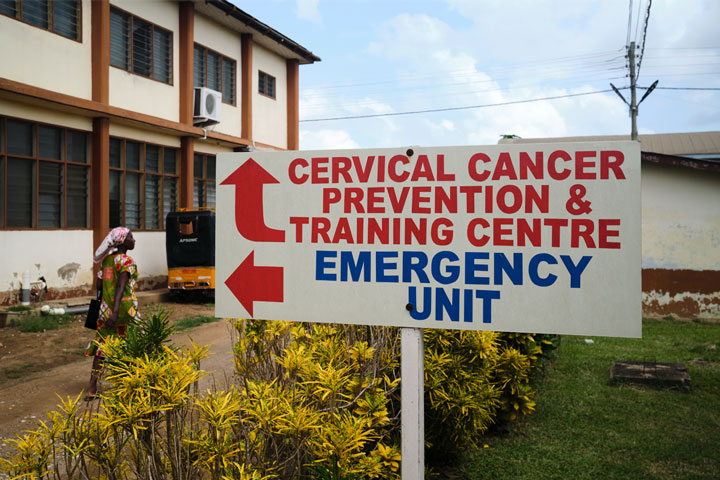

Investing in immunisation is part of investing in PHC and any PHC investments and delivery approaches should be holistic and integrated. This provides an opportunity to bring a variety of services to zero-dose children, their families and the communities they live in, such as nutrition and sexual and reproductive health – among others. No opportunity to meet the needs of historically neglected communities should be missed, and trust in public services must be restored to be sustainable and effective.

According to a 2019 study, "scaling up primary health care interventions across low and middle-income countries could save 60 million lives and increase average life expectancy by 3.7 years by 2030."4 If there is one critical investment governments should prioritise, it is remunerating community health workers – the heart of primary health care.

Community health workers' contribution and their knowledge of the cultures and languages of the communities they serve are widely recognised as essential, but paradoxically are usually not remunerated. They play a vital role in reaching zero-dose children and engaging with communities that often live in remote or fragile settings. As part of the same communities, they also suffer multiple deprivations, subsidising with their generosity entire health systems, and many of them are women.

According to a policy paper from Women in Global Health, a minimum of six million women are working in underpaid or unpaid community health worker roles. Based on 29 country case studies, these unpaid female health workers work primarily on maternal, child and reproductive health as well as health promotion.5 During the COVID-19 pandemic, they have taken on more public health and immunisation-related roles as well, increasing their workload, responsibilities and, potentially, risk.6 Informal recognitions and sporadic stipends are not enough. Formal recognition and fair pay are the ethical investment and should correspond to the multifaceted and complex challenges these community health workers face.

Building the world that we want means realising Universal Health Coverage, reaching zero-dose children and their communities with the full range of services they deserve. It means building health for all with political determination, full social participation and fair pay for the faces of primary health care: community health workers.

1. https://universalhealthcoverageday.org/

2. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/universal-health-coverage-(uhc)

3.Sim S.Y., Watts E., Constenla D., Brenzel L., Patenaude B.N. Return On Investment From Immunization Against 10 Pathogens In 94 Low- And Middle-Income Countries, 2011–30. Health Affairs, 2020 https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/pdf/10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00103

4. Stenberg, K et al. Guide posts for investment in primary health care and projected resource needs in 67 low-income and middle-income countries: a modelling study, 2019, The Lancet Global Health https://www.thelancet.com/journals/langlo/article/PIIS2214-109X(19)30416-4/fulltext

5. Health for the People: National Community Health Worker Programs from Afghanistan to Zimbabwe, edited by Henry B. Perry https://chwcentral.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Health_for_the_People_Natl_Case%20Studies_Oct2021.pdf