In conflict zones, authorising community health workers to administer vaccines can make all the difference

In Djenné, Mali, rising insecurity was sending immunisation rates into dangerous decline. A corps of specially trained health workers turned out to be the key to recovery.

- 3 February 2026

- 8 min read

- by Ibrahima Diarra

In the Senossa health area of Djenné, Mali, villages like Kotela, Koloye, Djimatogo and Siratintin remain virtually isolated for many months each year due to flooding and insecurity. With staff from government clinics unable to reach those cut-off populations with any regularity, community health workers have taken on an even greater share of responsibility for local health.

Nabo is one of them. She has been a community health worker (CHW) in Kotela, the community she hails from, for the past ten years.

Villagers trust her to provide care to people suffering uncomplicated cases of common illnesses like diarrhoea, malaria and pneumonia, as well as to help manage malnutrition in children under five. She’s the local node for behaviour change communication; she guides families on family planning and looks after pregnant women.

She keeps an eye on routine healthcare for children from birth up until 19 years of age, shepherding them through the vaccination schedule.

Once upon a time, that meant it was her job to make sure kids got the vaccines they needed from health centre staff. But since 2018, when Nabo underwent specialist training, she has stepped up to administer those vaccines herself.

Today, she spends her days armed with a government-provided coolbag of vaccines and her very own supply of courage, crossing small wooden bridges to reach children isolated by roaring waterways. “I wanted the children in my village to grow up healthy. Seeing a child fall ill for want of a vaccine that exists is unbearable,” Nabo said.

Her commitment has changed the lives of families. Aminata, a mother of two, says, “Before, I had to go all the way to Senossa or Djenné. Now my children get vaccinated here. It’s reassuring.”

Moussa, a neighbourhood leader, added: “The presence of CHWs has strengthened trust. Even in times of tension, parents know that their children will be protected.”

A vaccination vacuum threatens

Before Nabo and a corps of her colleagues began training up as vaccinators, immunisation rates had tumbled to dangerously low levels in Djenné.

Insecurity, geographical isolation and population mobility acted as hurdles to healthcare, with armed groups, community violence and seasonal flooding in the inner Niger Delta making it difficult to travel into and out of some health areas.

In 2019, just 19 CHWs had been trained up and authorised to administer vaccines. Today, all 76 CHWs in the district are vaccinators.

A ban on motorcycle traffic and the presence of improvised explosive devices landed as further disruptions to immunisation. A number of community health centres became utterly inaccessible, and vaccination workers left the rural areas. Vaccine coverage grew patchy; inequities of access grew worse.

It fell to community health workers – who were seen by residents as trustworthy members of the community, unlike, in many cases, health-centre based workers – to lead the work of repair.

Because they were accepted by armed groups, Nabo and her colleagues were therefore free to travel without restrictions. Their detailed knowledge of households facilitated the process of identifying unvaccinated or under-vaccinated children, which made them well-placed to gradually take on the work of administering vaccinations, in order to maintain access to services and protect the most vulnerable children.

When urgency demands innovation

The Djenné health district launched the pilot project that authorised CHWs to administer vaccines in 2019, but the practice was implemented gradually, in a coordinated manner, and under close supervision by the health district.

The CHW-based immunisation strategy has significantly improved equity and access to vaccination in the Djenné district.

The process began with discussions between the District Health Management Team and the health facility in charge of the area community health centres. These discussions provided an opportunity to consider the challenges, clarify all of the roles as well as the profile of CHW vaccinators, and develop a common approach together with the Community Health Associations (CHAs).

Have you read?

The CHWs who would be eligible for authorisation to administer vaccinations would need to match a specific profile: they had to be qualified as a nursing assistant or midwife, be indigenous or a resident, and be accepted by the community.

Eligible CHWs were counted and indexed in preparation, and hard-to-access health areas and villages were mapped. This made it possible to adapt the community health centre micro-plans to suit geographical and security constraints.

Next came training: all CHWs were trained by the health facility in-charge before being officially authorised to administer vaccines. Only at that point were they provided with supplies, equipment and cold chain devices.

Readying the ground

The need for vaccines and consumables like syringes at the sites was estimated based on a census conducted by the CHWs and other designated platform actors during home visits.

Village leaders were informed and mobilised to promote community buy-in, while self-defence groups got involved in order to facilitate and secure the transport of vaccines and supplies to vaccination sites on activity days.

The CHWs used national EPI tools to collect vaccination data. The data was sent to the community health centre technical managers, and was then consolidated at the health district level using the reporting channels already in place.

Credit: Centre National d'Immunisation

A key role in the community vaccination chain

In the seven years since launch, the programme has grown. In 2019, just 19 CHWs had been trained up and authorised to administer vaccines. Today, all 76 CHWs in the district are vaccinators.

These CHW vaccinators play a central role in community outreach and coordination. They identify and follow up on unvaccinated or under-vaccinated children, actively seek out cases, and strengthen communication for social and behavioural change related to vaccinations.

They also contribute to the continuity and quality of immunisation services in hard-to-reach areas by administering routine vaccinations, managing vaccines and supplies, ensuring data traceability, and taking part in monitoring and managing adverse events following immunisation. And they play a key role in managing rumours: they identify them, report them and prepare responses to them, in collaboration with religious and traditional leaders.

Credit: Centre National d'Immunisation

Despite instability, there are tangible results

The 76 CHWs in the Djenné district who have been providing vaccinations in areas inaccessible to community health centre teams collectively look after a population of 133,154 people, or 41% of the total population of the Djenné district.

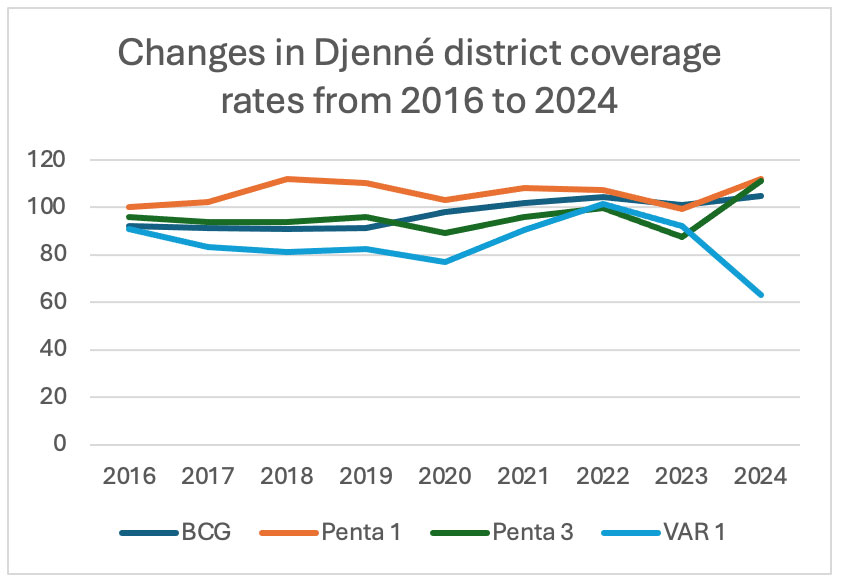

Despite the insecurity and severe access impediments, vaccination coverage has remained high, overall, and began to improve in 2021, all of which translates into good vaccination programme resilience.

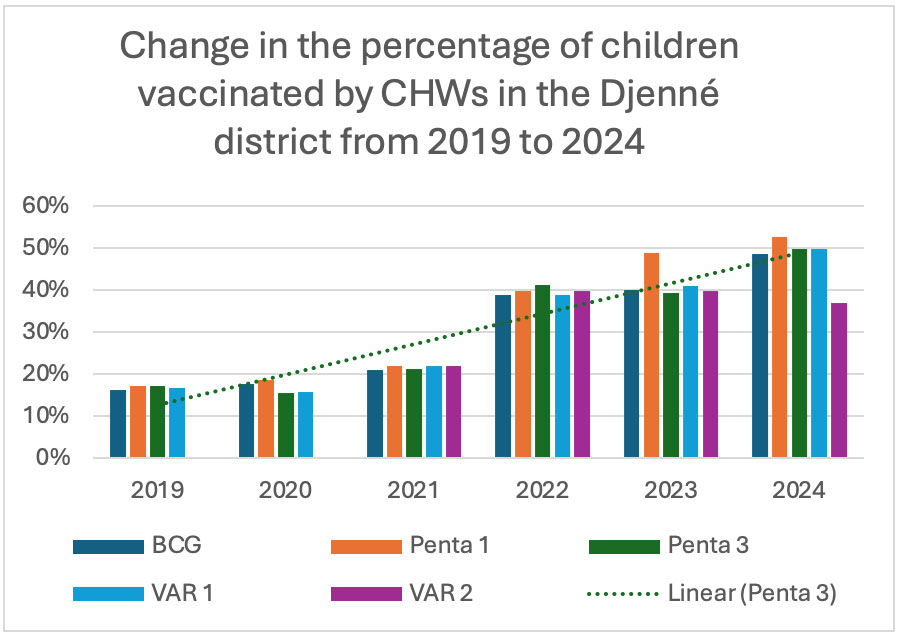

The CHWs’ contribution to vaccination increased significantly between 2019 and 2024, reaching almost half of the total number children vaccinated for a number of antigens. This reflects the growing strength and effectiveness of the community-based approach.

The increased involvement of CHWs has made it possible to improve access to routine vaccination and to reach zero-dose and under-vaccinated children who would have otherwise would not have received conventional services.

In other words, the CHW-based strategy has significantly improved equity and access to vaccination in the Djenné district by sustainably bringing services closer to populations living in isolated areas and in areas that are at risk of or impacted by forced displacements.

Adapted solutions give rise to operational challenges

The success of this experiment has depended not only on the commitment and skill of the CHWs, but also on finding timely solutions to the many difficulties that arose.

These included challenges related to insecurity, geographic isolation and health system constraints. Supervision was impacted by travel limitations, while CHW motivation was affected by limited incentives and heavy workloads. Logistical constraints such as tool shortages and problems with accessing appropriate cold chain equipment were exacerbated during the rainy season.

In response, the district and its partners implemented pragmatic solutions: targeted formative supervision when conditions allowed, improved availability of standardised tools, enhanced motivation and logistical support (bonuses, motorcycles and fuel), and CHW involvement in EPI microplanning.

A few important takeaways

The Djenné experiment highlights several key lessons for strengthening the equity of vaccine access:

- the permanent presence and community proximity of CHWs can reduce the number of zero-dose children, improve follow-up vaccination rates, and strengthen social mobilisation;

- the quality and regularity of supervision is crucial to maintaining performance, and justifies the use of off-site or remote supervision methods in contexts where access is difficult;

- the motivation and recognition of CHWs are key to sustainable results

- lastly, community coordination and advanced strategies that involve the local leaders and intermediaries are essential to maintaining the acceptance of vaccines and reaching children living in the most remote areas.

Sustainability: firmly embedding CHW-administered vaccination into the health system

The sustainability of CHW-administered vaccinations in Djenné and the scaling up of the programme depends on its gradual integration into the regular operations of the health system.

Experience has shown that the continuity of basic health services in these contexts, including vaccination, is closely linked to the ability to maintain a structured, supported and supervised community system over time.

This past July, a national strategy was adopted that institutionalises CHW-administered vaccinations in conflict zones that are difficult to access. This is a major step forward in ensuring the sustainability of this approach. It is backed by the deployment of a digital tool for CHWs, namely the District Immunization Strengthening Consortium – Mali, which facilitates the collection and reporting of vaccination data at the community level, thereby improving the monitoring and management of activities.

Beyond formalisation, the sustainability of the system also requires micro-plans that are adapted to conflict realities, realistic working conditions for CHW vaccinators, and which provide for financial and logistical incentive mechanisms. It also requires the continuous availability of vaccines, inputs and equipment adapted to hard-to-reach areas.

Finally, the support of technical and financial partners is essential to consolidating this community-based system as a sustainable lever for strengthening vaccine equity and reaching zero-dose and under-vaccinated children.