Could a new vaccine help stop the deadly MERS coronavirus?

Early trial results suggest an experimental vaccine gives long-lasting immunity against the Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) coronavirus.

- 9 February 2026

- 5 min read

- by Linda Geddes

At a glance:

- MERS is a rare but often deadly coronavirus infection that circulates in camels and can spill over into humans in unpredictable outbreaks. There is currently no licensed vaccine or specific treatment, making prevention a key goal for global health preparedness.

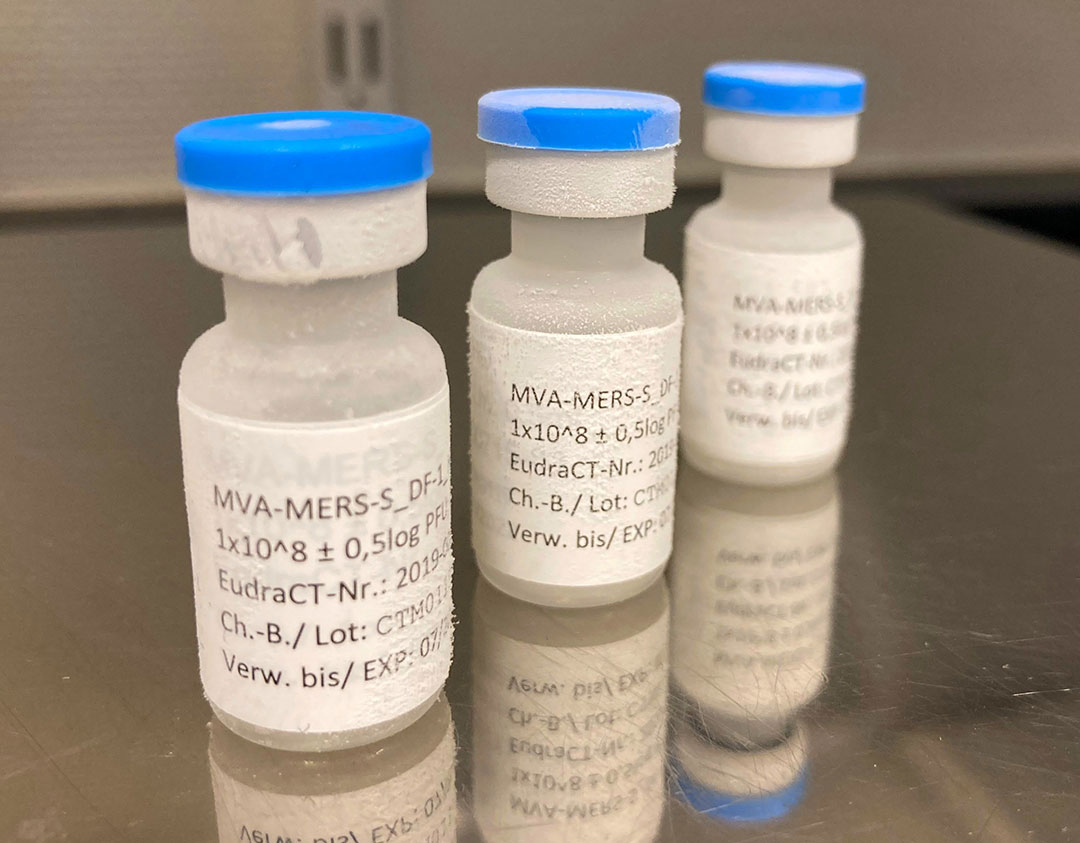

- A new study published in Nature Communications found that an experimental vaccine known as MVA-MERS-S called triggered immune responses that lasted at least two years after participants received three doses of it. Many still had virus-blocking antibodies and T cells, which are both important for long-term immune memory.

- The findings show that long-lasting immunity against MERS is possible. However, the study did not test whether the vaccine actually prevents infection or severe disease, and delivering multiple doses may be challenging in emergency outbreak settings.

An experimental vaccine against the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) has produced durable immune responses lasting at least two years in human volunteers – a milestone that researchers say strengthens global pandemic preparedness.

Although the new study did not test whether the vaccine prevents infection or severe disease, it suggests that long-lasting immunity against MERS could be achievable through immunisation.

What is MERS?

First discovered in Saudi Arabia in 2012, Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) is a severe respiratory disease with a fatality rate of up to 36%. It continues to circulate in animal reservoirs like dromedary camels.

It belongs to the same family of viruses that cause COVID-19, severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and common colds, and has been responsible for more than 2,600 human infections in at least 27 countries since it first emerged.

While human cases remain rare, its high death rate and sporadic outbreaks have made it a priority pathogen for research and development by the World Health Organization (WHO). To date, no licensed vaccine against MERS exists – although several are in development – and there is no specific antiviral therapy.

How does the experimental MERS vaccine work?

The vaccine candidate, known as MVA-MERS-S, is a viral-vector vaccine similar in concept to the Oxford AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine.

Both use a harmless virus (the vector) to deliver genetic instructions that teach the immune system to recognise a dangerous pathogen.

In this case, the vector is Modified Vaccinia Ankara – a highly weakened poxvirus that has been engineered so it cannot replicate in human cells – that has been genetically tweaked to deliver the instructions for making the MERS coronavirus spike protein to human cells.

After vaccination, these cells briefly produce the MERS spike protein, which acts as a training signal for the immune system. It means that if a vaccinated person later encounters the real MERS coronavirus, their immune system should be able to recognise the spike protein quickly and respond faster and more effectively.

How effective is this MERS vaccine candidate?

An earlier phase I clinical trial in healthy adults in Germany and the Netherlands found the vaccine to be safe and capable of inducing both antibody and T-cell responses, after participants received three doses delivered in a prime-boost schedule over several months. This means they received an initial dose, followed by booster shots to reinforce and extend protection.

The latest study, published in Nature Communications, analysed immune markers in 48 of these participants two years after their final dose.

Have you read?

The researchers found that a substantial proportion still had neutralising antibodies capable of blocking the virus, along with specialised immune cells known as T cells. Notably, antibody levels at this point were comparable to those seen after the second vaccination.

“That we were able to measure such a stable immune response two years after the last vaccination was by no means a given,” said study author Dr Leonie Mayer from the Institute for Infection Research and Vaccine Development (IIRVD) at the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf. “Our results show that an additional booster vaccination significantly improves long-term immunity.”

What are the implications of this research?

While no vaccine against MERS has yet been licensed, these long-term results help to close an important knowledge gap by showing that vaccine-induced immunity can persist well beyond the first few months after immunisation – a key consideration for diseases that flare up unpredictably, such as MERS.

“This study represents another important step in global preparedness for emerging viruses,” said Prof Marylyn Addo, the study’s scientific lead, and director of the IIRVD. “It shows that we can develop vaccines that not only have short-term effects but also elicit long-lasting immune responses. This knowledge is crucial for containing future outbreaks at an early stage, particularly in high-risk populations, and for better protecting society.”

Despite the encouraging results, the researchers stress that strong immune responses don’t automatically mean real-world protection. The study wasn’t designed to test whether the vaccine prevents MERS infection or severe illness, and scientists still don’t know exactly what level of immunity is needed to achieve this.

Also uncertain is how practical it would be to deliver a booster dose several months after the initial immunisations during a fast-moving outbreak. “As MVA-MERS-S requires at least two doses to elicit neutralising antibodies, this vaccine might be less optimal for emergency vaccination schemes in an acute outbreak setting,” the researchers said.

However, they added that the vaccine could still play an important role in preparedness and prevention, particularly for people at elevated risk of exposure: “While a three-dose schedule may not be practical for a sudden MERS outbreak, it could offer long-lasting protection for those already at highest risk of infection. This includes camel workers in regions where MERS-CoV is actively circulating among camel herds,” Mayer told VaccinesWork.

Are other vaccines against the MERS coronavirus being developed?

Several other MERS coronavirus vaccines are in development, though none have yet been approved for use. A handful have reached early human trials, including a DNA-based vaccine co-developed by GeneOne Life Science in South Korea and US-based Inovio Pharmaceuticals, and a viral vector vaccine from the Oxford Vaccine Group, which uses the same adenovirus vector as the Oxford AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine.

Further approaches – including protein subunit and nanoparticle vaccines – are being tested in laboratories and animal studies.