COVID variants: could dangerous new ones evolve in pets and farm animals?

Early results from several studies have found that pets can pick up COVID-19 from their owner – but they are unlikely to be dangerous as a result.

- 7 July 2021

- 5 min read

- by The Conversation

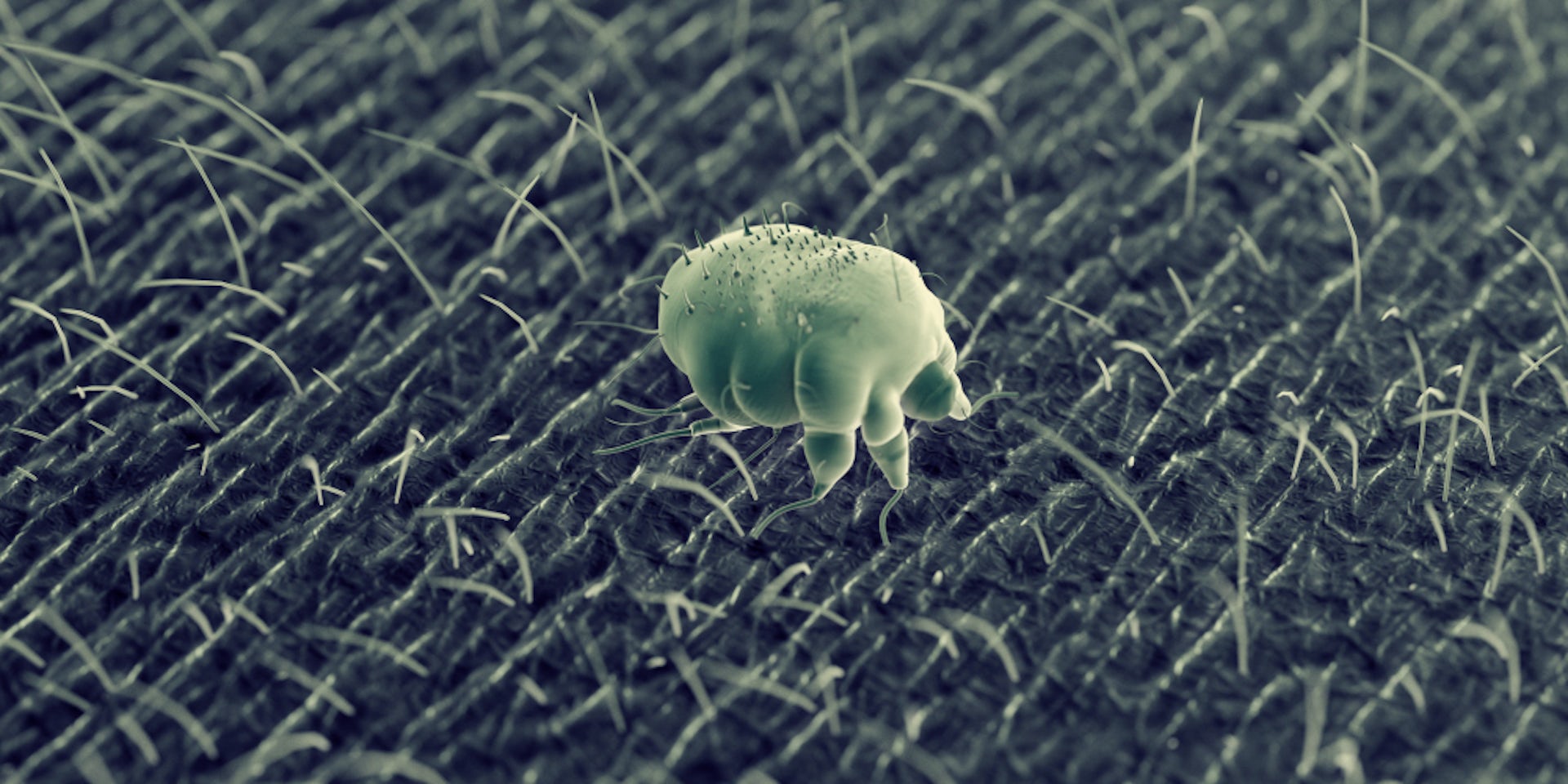

People have been panicking about COVID-19 in animals since the very start of the pandemic. There’s now plenty of evidence that SARS-CoV-2 – the coronavirus that causes COVID-19 – can cross from humans into other animals. This is known as spillback. The virus is capable of infecting a range of species, from hamsters to gorillas.

Reassuringly, the vast majority of animals do not get as seriously sick from an infection as humans do. Also, at present there are very few documented cases of animals then transmitting infection back to humans. But a new concern is now being discussed: what if SARS-CoV-2 could be replicating unnoticed in animals and mutating? Could new variants emerge that can reinfect humans and create more havoc?

SARS-CoV-2 has been evolving in humans throughout the pandemic, resulting in many new variants arising, and there are two factors that appear to have helped variants emerge. First is the vast number of infections in people worldwide, as the virus has the chance to mutate every time it reproduces. The second is the much smaller number of chronic infections that happen in people whose immune systems aren’t fully functioning. When facing a weak immune system, the virus isn’t quickly wiped out, and so has the time to evolve ways of evading immunity.

Is it possible that these evolution scenarios are also going on in animals, but that we’re unaware of them happening?

To get a sense of whether this is a risk, we first need to know how many infections are occurring in animals. This will help identify any possible hidden reservoir of the virus. To this end, SARS-CoV-2 infections in animals are being studied extensively in many places across the world. Scientists are investigating exactly which species are susceptible to infection, as well as how common the virus is in different animal populations.

To find out which species are susceptible, many different animals – both domesticated and wildlife species – have now been exposed to the virus in experimental settings. This has provided a comprehensive understanding of exactly which animals can be infected – they include cats, ferrets, deer mice and white-tailed deer. And to find out how common animal infections are, screening for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies is also being used to uncover animals that have previously been naturally exposed to the virus.

Most studies of natural infections in animals have focused on cats and dogs, as these are the species that live most closely with humans. A recent UK preprint (a piece of research yet to be reviewed by other scientists) found that only six out of 377 pet dogs and cats tested between November 2020 and February 2021 had antibodies specific for SARS-CoV-2.

This shows that infection isn’t rife and going unnoticed among most of our pets. Early results from another study in the Netherlands (which is also still awaiting review) found higher rates of antibodies in the animals it tested (54 out of 308 dogs and cats were positive), but probably due to different sampling strategies. The UK research studied blood samples from a random set of animals, whereas the Dutch study specifically sampled pets in the homes of people known to be infected with COVID-19.

Have you read?

So it’s reasonably safe to say that our household pets are unlikely to be acting as a significant reservoir of ongoing infections that could allow new variants to emerge. But what about other species?

The animal that has raised most concern is mink. The only documented cases of animals spreading SARS-CoV-2 back to people involve these animals. These were first identified in the Netherlands in May 2020 and mink-related variants were identified in Denmark in November 2020. Thankfully, highly effective containment measures have rapidly brought mink infections under control in these areas – but these animals will need to continue to be monitored closely.

Can animals be immunosuppressed?

What about the other source of virus variants: chronic cases of COVID-19? Could these occur in animals, enabling more virus evolution within a single host?

Typically, chronic SARS-CoV-2 infections occur in people whose immune systems aren’t fully functioning – often because of other medical conditions they have or treatments they are receiving. These immunosuppressed patients therefore receive extensive medical care throughout their infection.

Animals can also be immunosuppressed for a whole range of reasons, but even the most beloved pets rarely undergo the kind of extensive hospitalisation that could allow for viral evolution. As for immunosuppression in other animals, such as wildlife, this would be a significant survival disadvantage. It’s unlikely that animals with compromised immune systems would survive long enough for much evolution of an acute virus like SARS-CoV-2 to happen. However, minor mutations have been reported in experimental infections (again in early research awaiting review), suggesting that some evolution is theoretically possible even over a short timeframe.

Moving forwards, it’s essential that we continue surveillance for SARS-CoV-2 in all manner of animal populations. Particular focus should be on animals that live more closely with people – it is pets and farmed animals that are more likely to be accidentally exposed to high doses of virus from an infected person. Careful attention must also be paid to wildlife known to be susceptible to infection.

If evidence of natural animal-animal spread or chronic infections in animals arises, then strict control measures must be introduced quickly. At present, there is no need to consider similar blanket control strategies for animals like those used in humans, but we should keep an open mind for the future.![]()

Authors

Sarah L Caddy, Clinical Research Fellow in Viral Immunology and Veterinary Surgeon, University of Cambridge

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Disclosure statement

Sarah L Caddy does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Partners

University of Cambridge provides funding as a member of The Conversation UK.