Drought may affect routine immunisation in Africa, study finds

Climate change is set to transform global health. A new study has found that droughts – one product of extreme weather exacerbated by climate change – may already be impacting rates of vaccination.

- 8 October 2021

- 3 min read

- by Maya Prabhu

Drought may impede routine immunisation coverage in Africa, according to a new study that looked at survey data collected in 22 countries between 2011 and 2019.

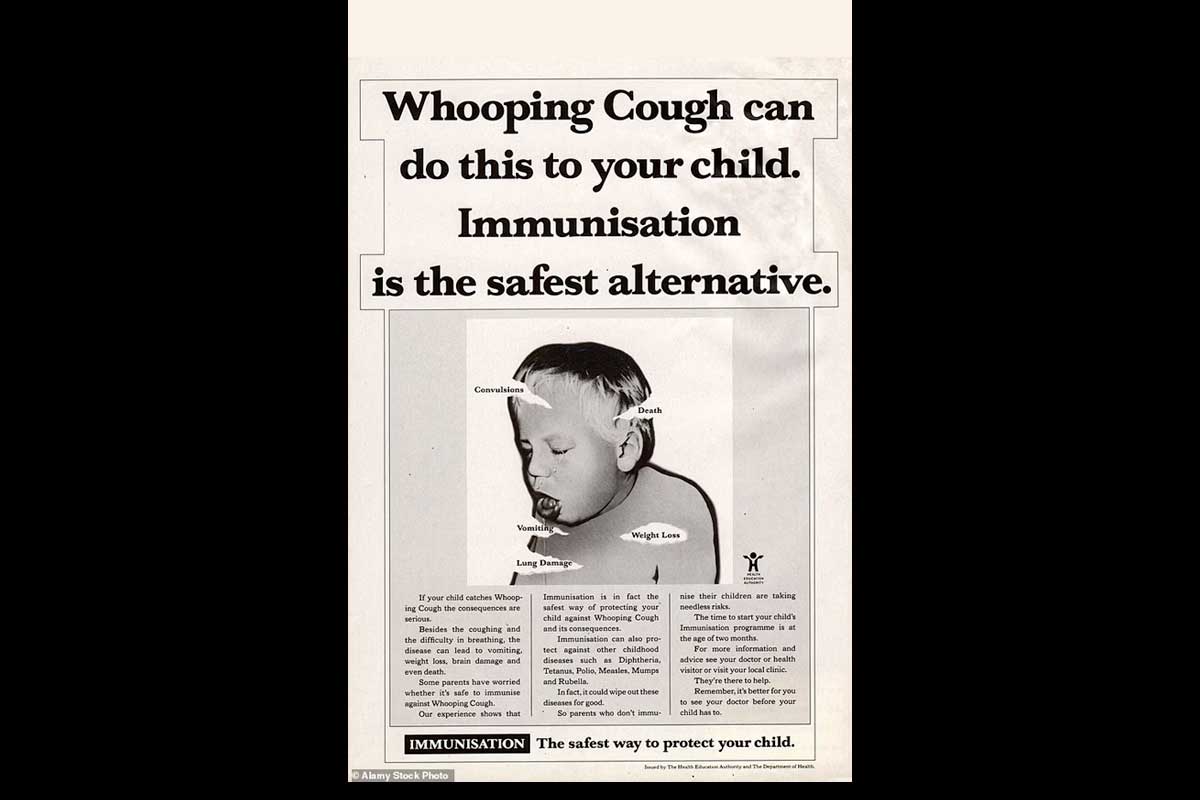

Drawing on Demographic and Health Surveys data for a total of nearly 140,000 children, researchers found that drought was associated with lower odds of completion of childhood Bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG), diphtheria, tetanus and pertussis (DTP) and polio vaccinations. The findings are particularly concerning given that climate change has already driven an increase in droughts, and is likely to continue accelerating the incidence of extreme weather events of all kinds.

In some cases, droughts spark wildfires, potentially restricting mobility and damaging healthcare infrastructure.

Previous studies have recorded an association between drought and childhood illness. One study that surveyed nearly 2,000 children in Uganda between 2009 and 2012 found that periods of drought saw a higher incidence of coughs, fevers and diarrhoea, leading the researchers to suggest that poor nutrition, arising from low rainfall, may have left the children more vulnerable to infection.

Certainly, the acknowledged risk of disease outbreaks during droughts has motivated health policy-makers to make vaccination campaigns a priority in affected regions in the past. During 2016’s drought in Ethiopia, for instance, the government and partners, including UNICEF and WHO, launched a reactive campaign to vaccinate 25 million people nationwide against measles. Similarly, in 2017, Gavi launched a campaign to immunise 450,000 at-risk people in drought-hit Somalia against cholera.

Have you read?

But if droughts hamper uptake of routine childhood vaccinations – which are, as the authors of the new study write, “one of the most impactful interventions to prevent childhood illness” – leaving them unprotected in times when their natural defences are depressed, children face a doubled threat.

Paradoxically, the increased rates of illness amid droughts may be part of what is driving down routine immunisation uptake. “Parents may avoid vaccination when their children are ill due to perceptions that the vaccination could exacerbate illness, exacerbate symptoms, or produce pain,” write the researchers. Other possible reasons for the downturn in vaccination rates amid drought include food insecurity and financial strain, which may leave parents unable to pay for healthcare or transport to clinics, or suffering the mental health impacts associated with material stresses. In some cases, droughts spark wildfires, potentially restricting mobility and damaging healthcare infrastructure.

“Healthcare programs need to be prepared to effectively provide clinical and preventive care amidst the changing climate,” said the study’s co-lead author Jason Nagata. That goes far beyond reckoning with the potential impact of drought on vaccination. As Linda Geddes wrote for this publication, as the planet warms, vector-borne illnesses like malaria and dengue are likely to spread further and faster, and water-borne illnesses like cholera may become a larger threat amid unusually dry or wet weather.